This Article From Issue

July-August 2013

Volume 101, Number 4

Page 310

DOI: 10.1511/2013.103.310

THE AGE OF EDISON: Electric Light and the Invention of Modern America. Ernest Freeberg. xiv + 354 pp. Penguin Press, 2013. $27.95.

In his now-classic 1998 study Edison: A Life of Invention, Paul Israel, director of the Thomas A. Edison Papers Project at Rutgers University, wrote:

Edison, the uncommon common man, had become a revolutionary figure akin to the founding fathers. He did not just invent new and useful things but changed the way men and women lived.

The inventor figures prominently in Ernest Freeberg’s The Age of Edison: Electric Light and the Invention of Modern America. This superbly written book is a fine complement to Jill Jonnes’s biographical work Empires of Light: Edison, Tesla, Westinghouse, and the Race to Electrify the World (2003): The Age of Edison offers a broad discussion of the social implications of this new technology.

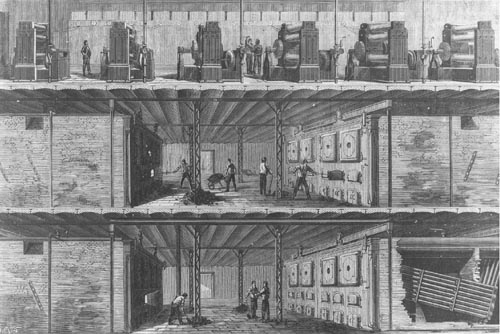

From The Age of Edison. Image courtesy of U.S. Dept. of the Interior, National Park Service, Thomas Edison National Historical Park.

Freeberg, a professor of history at the University of Tennessee, begins his narrative in fall 1879, at Edison’s Menlo Park laboratory, with a riveting account of his search for a viable and economical filament for his electric lightbulb—one that “could handle the tremendous heat of an electric current and, when placed in the protective atmosphere of a vacuum bulb, would incandesce, glowing instead of burning up.” After testing a variety of carbon filaments, Edison finally settled on “a simple filament of carbonized cotton thread,” which was tested on October 22, 1879, and which glowed for approximately 14 hours.

One of the author’s tasks is to correct the misconception that the electric lightbulb was a product only of Edison’s solitary work—a notion that is, Freeberg notes, “more hero worship than history.” He goes on, “A closer look at how Edison, his partners and his rivals developed the first working electric lights shows that the inventor does not pull insights from a void, like a bulb suddenly illuminating a dark room, but that invention is a complex social process.” Accordingly, he examines work by Edison’s rivals in the field, most notably the British chemist Joseph Swan and U.S. inventor Charles F. Brush. Reaching further back in history, he recounts the contributions of Alessandro Volta (1745–1827), Sir Humphry Davy (1778–1829) and others. We learn, for example, that it was Davy who demonstrated incandescence, “producing light by passing an electrical current through a platinum wire, making it hot enough to glow.” Davy’s wire, Freeberg writes, was “the first ancestor of Edison’s lamp, and every incandescent bulb ever since.”

After providing a solid background on the development of electric light, Freeberg offers a historical and organizational account of the profound social changes wrought in the United States by the advent of that technology—changes that affected the arts, social legislation and even the practice of medicine. He includes chapters on early public opinion about the electric lamp; effects of electric light on work and leisure; the rivalry between the early gas and electric companies; the Rural Electrification Act of 1936, which provided power to the hinterlands of the nation; and finally the nature and origins of American inventiveness, which many attribute primarily to the U.S. patent system.

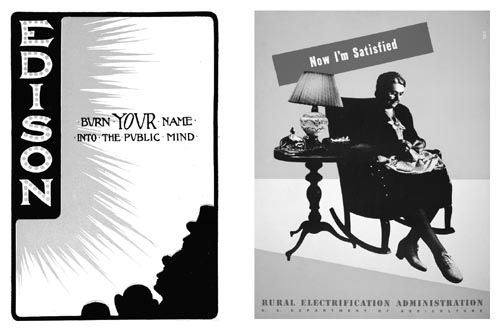

From The Age of Edison.Advertisement at left courtesy of The Huntington Library, San Marino, California. Advertisement at right courtesy of U.S. Dept. of Agriculture/Library of Congress

The book also includes numerous black-and-white illustrations, reproductions of vintage lithographs, photographs and political cartoons dealing with this early period in lighting technology. The meticulously researched and documented text offers plenty of fascinating historical detail. In a short epilogue titled “Electric Light’s Golden Jubilee,” Freeberg tells of an event organized in 1929 by Henry Ford to celebrate the 50th anniversary of Edison’s perfection of the first viable lightbulb. During the celebration, which was broadcast internationally by radio, Edison took part in a radio play “designed to recreate the mythical moment when he tested his first successful carbon-filament lamp.”

The Age of Edison is destined to become a standard work on its subject. The book will interest a broad spectrum of readers—historians of science, students in high school science classes and nonspecialists alike.

Harold M. Green is a writer and lecturer in Liberty, N. Y. His primary areas of interest are the history of U.S. sociology and psychology. He has also written about the golden age of radio comedy and pioneers of radio broadcasting in the United States. He is an emeritus member of Sigma Xi.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.