Nanoparticle Visions

By Robert Frederick

Too small to be seen by the human eye, nanoparticles are already transforming many scientific fields, from electrical engineering to materials science. Now scientists are working to optimize production.

Too small to be seen by the human eye, nanoparticles are already transforming many scientific fields, from electrical engineering to materials science. Now scientists are working to optimize production.

In a recently expanded lab at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory, Yevgeny Raitses and his colleagues are using a variety of techniques to study nanoparticle formation via plasma—hot, ionized gas, also called the fourth phase of matter. “What’s unique in our research,” Raitses says, “is that there’s never been such an integrated, team effort by such a diversified group.”

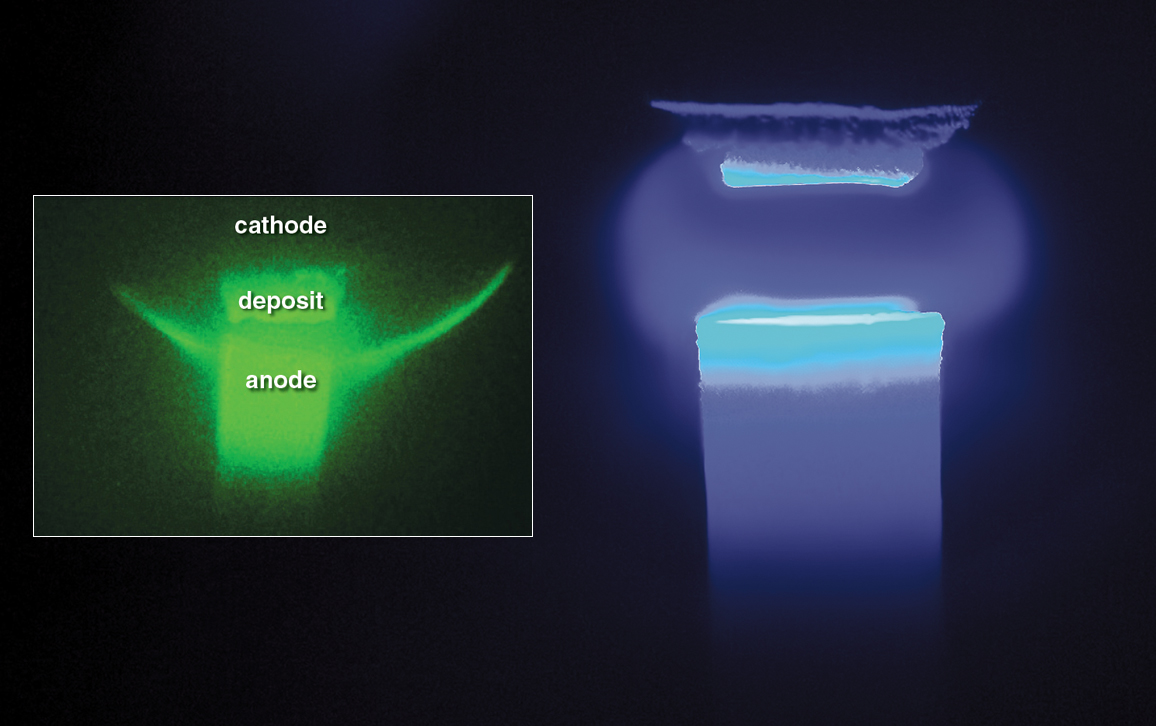

The team consists of theorists and experimenters, modelers, materials scientists, physicists, and chemists. Their basic research, funded by the DOE’s Basic Energy Sciences program, will inform how to optimize plasma-based nanosynthesis, which has proven a challenge even after decades of research on carbon-arc nanosynthesis (vaporizing carbon via an arc of electric current between anode and cathode, below).

Photo at the left by Shurik Yatom. Photo on right by Vlad Vekselman and Elle Starkman.

Carbon nanotubes, wanted for their remarkable electrical conductivity and strength, were first produced in 1991 by Sumio Iijima at Japan’s NEC Corporation. Since then, experimentation has shown what works and what doesn’t in terms of production, but only from an end-product result, meaning it hasn’t led to techniques to produce reliably high-quality nanoparticles at low cost. “So what we’re trying to do is understand the details of the nanoscale physics that are going on,” says Raitses, “and perhaps, if we’re successful, we can suggest methods of improving plasma nanosynthesis.”

The form of carbon-arc plasma nanosynthesis the team is studying takes place in a chamber filled with an inert gas, such as helium, at normal atmospheric pressure. With sufficient current, the anode (the positively charged electrode made from carbon) is vaporized—at a rate of a few milligrams per second—first becoming gaseous before being ionized (where positively charged ions and free electrons separate) to become plasma. The plasma then condenses as nanoparticles on the cathode (the negatively charged electrode). Temperatures are between 3,200 and 3,500 kelvin.

“We selected carbon nanotubes and carbon arc because there’s a huge amount of work done by scientists around the world,” says Raitses, “so it’s a convenient benchmark to test our approaches, our diagnostics, our modeling.” After that, the team plans to study the formation of other nanoparticles by plasma nanosynthesis.

“Carbon is just the starter,” Raitses says, but it’s a starter that, if successful, could transform many scientific fields that already employ carbon nanotubes—from electrical engineering to materials science—fields long frustrated by the current shortcomings of carbon nanotubes.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.