Short takes on five books

By Linda Schmalbeck, David Schneider, Roger Harris, Christopher Brodie, Greg Ross

The Cartoon Guide to Chemistry · Patents · The Andes · Oak · What's Out There

The Cartoon Guide to Chemistry · Patents · The Andes · Oak · What's Out There

DOI: 10.1511/2006.58.187

THE CARTOON GUIDE TO CHEMISTRY. Larry Gonick and Craig Criddle. HarperResource, $16.95.

For teachers on the lookout for accurate and entertaining classroom material, cartoonist Larry Gonick's wonderful series of guides on topics as diverse as American history, physics and sex is a godsend. The latest addition to the group, coauthored by Gonick and Stanford environmental engineering professor Craig Criddle, is The Cartoon Guide to Chemistry.

From The Cartoon Guide to Chemistry

You don't need to be an instructor to enjoy the novelty and unexpected comprehensiveness of this cartoon treatment of chemistry. The lessons are spiced with the antics of a hapless, pun-prone alchemist and a well-chosen assortment of historical figures that are more or less accurately presented. Any reader interested in brushing up a bit on topics like "equilibrium" or "heats of reaction" will appreciate the authors' light touch.

Conveniently, the book adheres rather closely to a standard introductory chemistry curriculum and even, good grief, works through a reasonable number of calculations! Surprisingly for such a slim and entertaining volume, the table of contents looks respectably like that of any number of textbooks used by high school students or college freshmen. The book moves with wit and humor from atomic theory to thermodynamics to electrochemistry, even including quite a decent index and an appendix with instructions on how to use logarithms.

The authors have used the liberating medium of a comic book to produce a chemistry companion that can be read in one or two short and amusing sittings and will lead to a clearer understanding of the chemists' world.—Linda Schmalbeck

PATENTS: Ingenious Inventions: How They Work and How They Came to Be. Ben Ikenson. Black Dog and Leventhal Publishers, $19.95.

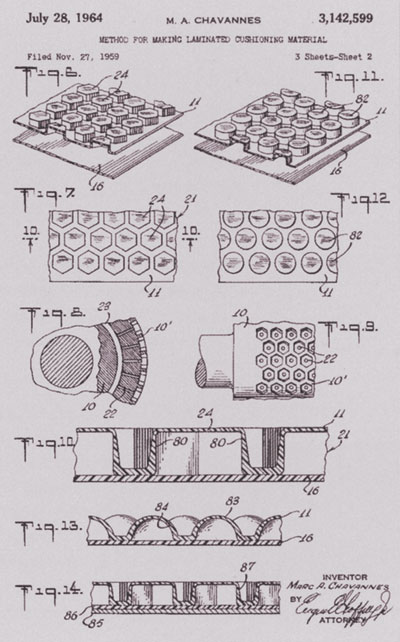

A copy of Ben Ikenson's book Patents appears at first glance to have just come out of the box, with plastic packing material clinging to it. Only after probing this charming survey of more than 100 famous and not-so-famous inventions does one realize that the book's unsightly cover is, in fact, an homage to one of the inventions described therein—Bubble Wrap, which received U.S. patent number 3,142,599 in 1964 (right). As Ikenson explains, Bubble Wrap, like many influential inventions, began with some garage tinkering and ended up revolutionizing an industry.

From Patents: Ingenious Inventions

Although this compendium covers such well-known inventions as the lightbulb, the airplane and television, the real value of the book is in the equal weight it gives to many of the offbeat inventions that also shaped modern culture: the Slinky, Post-It Notes and Band-Aids, for example. One can't help but chuckle over many of the facts that Ikenson unearths about them.

Technophiles looking for insights into operating principles will, however, be disappointed. Ikenson provides a section titled "How It Works" with each entry, but these descriptions often fall short of what's needed for clear understanding. And historians of science and technology will have no trouble spotting errors or oversights. To give one instance, Ikenson's description of the history of the air bag misses completely the fact that the roots of this invention reach back to World War II, when air bags were first devised to protect the occupants of aircraft.

Still, Patents is a pleasure to explore. And one can have some fun, too, popping the bubbles on the cover.—David Schneider

THE ANDES: As the Condor Flies. Tui De Roy. Firefly Books. $35.

In The Andes, world-famous photographer Tui De Roy takes the reader on a journey of mythic proportions down the mountain range's full 4,500-mile length. The book's 350 images, some of which are stunning, maintain the high standards set by De Roy in her photographs of Galápagos Islands wildlife. Some of the most remarkable pictures—like the one to the right of a young condor flying high above the snow-tipped peaks lining the Colca Canyon—integrate wildlife into the landscape.

From Andes: As the Condor Flies

De Roy shows a flair for nature writing. The book offers an introduction to the biogeography and biodiversity of Andean habitats. But in some passages, her words take on a fantastical quality reminiscent of the prose of William Beebe or Laurens van der Post, as in her description of the Bolivian altiplano as "a fairytale land of color, space, and sheer wonder; a wild land of raw, frigid winds and smooth, sunwarmed stones, of few people and teeming wildlife." I found the combination of personal anecdote and natural history delightful.

The book is an unashamed testament to the beauty of wilderness. Its lack of coverage of environmental issues facing the Andean region gives it an element of escapism. But readers will be left longing to visit the area, for, as De Roy says, "To walk among these mountains is to taste the spirit of freedom that only utmost wildness can convey."—Roger Harris

OAK: The Frame of Civilization. William Bryant Logan. W. W. Norton, $24.95.

Arborist William Bryant Logan covers a lot of ground in Oak: The Frame of Civilization. His thesis, that "no tree has been more useful to human beings," is buttressed by compelling arguments, which hint at a lifelong affection for the genus Quercus in all its variety.

From Oak: The Frame of Civilization

Oak forests are strangely communal, sharing food through a contiguous root system. Oaks share with other species too, often supporting hundreds or thousands of fungi and animals, including humans. Logan makes a case that balanoculture—the eating of acorns—was once prevalent. Perhaps for that reason, oaks became an important part of ancient societies.

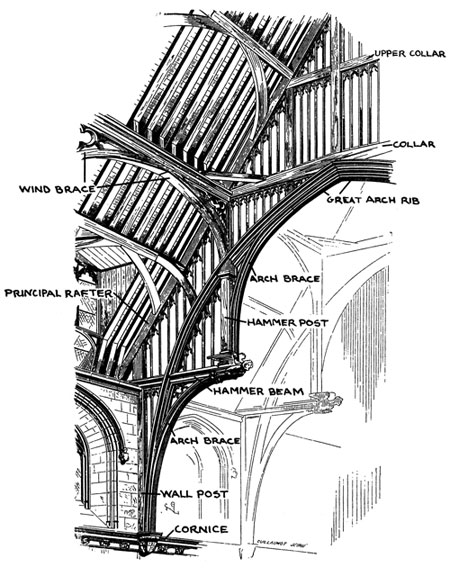

The Celts associated wisdom with oak-knowledge, and the honorific name druid stems from the roots dru, or oak, and wid, to see or to know. In medieval Europe, carpenters sat with the priests in the great halls of kings, and according to Logan, "the greatest work of art of the European Middle Ages is . . . 660 tons of oak, the timber-framed roof of Westminster Hall." The roof's structure is shown above; engineers still disagree on exactly how it distributes forces. The U.S. Constitution and the Declaration of Independence were drafted with oak-gall ink. The republic they founded commissioned the U.S.S. Constitution to be built from 1,500 oaks from New England and the Sea Islands of Georgia, and its 22-inch-thick live-oak sides proved strong enough to repel a cannon blast, earning the vessel its nickname, "Old Ironsides."

After a stroll through this great garden of a book, readers will have difficulty resisting its claim that oak trees have an important, underappreciated place in human history.—Chris Brodie

WHAT'S OUT THERE: Images From Here to the Edge of the Universe. Mary K. Baumann, Will Hopkins, Loralee Nolletti and Michael Soluri. Duncan Baird, $29.95.

The simply titled What's Out There is a striking gazetteer of our universe, a picture dictionary of astronomical images from Asteroid to White Dwarf. The authors spent two years reviewing 10,000 images before choosing 180, many of them stunning and some of them previously unpublished. A coronal mass ejection large enough to engulf Earth erupts from the Sun's surface. Infrared cirrus glows like a frozen cosmic firestorm. A rare shot of Earth eclipsing the Sun, taken quickly by Apollo 12, is a masterpiece of stark composition. The Cone Nebula is a giant column seven light-years "tall" in the constellation Monoceros (see the Hubble image at right).

From What's Out There: Images from Here to the Edge of the Universe

The volume includes an illuminating essay on the significance of color in astronomical images, and a useful appendix describes the 37 instruments used to gather the images. This material illustrates how much we still have to learn, but that's part of the point. "Science after finding all the answers would be like mountaineering after Everest," writes Stephen Hawking in a brief foreword. "It would be boring to have nothing left to discover."—Greg Ross

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.