Climate Control in Termite Mounds

By Robin Lynn Arnette

X-ray–based imaging reveals the natural ventilation structures that these insects build into their homes.

X-ray–based imaging reveals the natural ventilation structures that these insects build into their homes.

When architects design a building, they may plan extensively around factors such as whether it will be aesthetically pleasing, or how much eco-friendly material will be used in its construction. But termites, one of nature’s most gifted structural engineers, build dwellings that hold hundreds, thousands, or millions of individuals without any planning or direct communication with one another. Large structures, human or insect made, also have to take climate control into account. The internal temperature of termite mounds remains relatively constant, even when outside temperatures can fluctuate by 20 degrees Celsius. Understanding the mechanisms behind these ventilation systems could give architects new tools to apply to buildings for people.

To study how termites optimize mound ventilation, temperature, and humidity, a European research team adopted an imaging method used in medicine—computed tomography (CT)—and a closely related technique, x-ray microtomography. These technologies work at different scales, but both use x-rays focused on thin areas of an object. They create sectional images that are then combined in a computer to output a scan of the entire internal structure of the object. Geological engineer Kamaljit Singh of Heriot-Watt University in Edinburgh, along with one of his doctoral students, Nengi Fiona Karibi-Botoye, worked with animal behaviorist Guy Theraulaz from the University of Toulouse in France to produce numerous, highly intricate images of termite mounds, the analysis of which the group recently published in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface.

To make their mounds, termites take bits of sand, clay, and feces into their mouths and fuse them together with saliva. Mounds are usually most noticeable above ground, but they can also be formed completely underground or in trees, among other places. On the inside, the mound is compartmentalized, with chambers set aside for particular functions. Generally, the queen’s chamber is near the bottom, and her only job is to lay eggs. Workers transport the eggs to another chamber. This dedicated nursing corps of workers tends to several other chambers that contain larvae at various developmental stages. There are also chambers where workers grow mushrooms to feed the larvae. All of these rooms are connected by small corridors.

N. F. Karibi-Botoye et al., Journal of the Royal Society Interface 22:20250263 (all images)

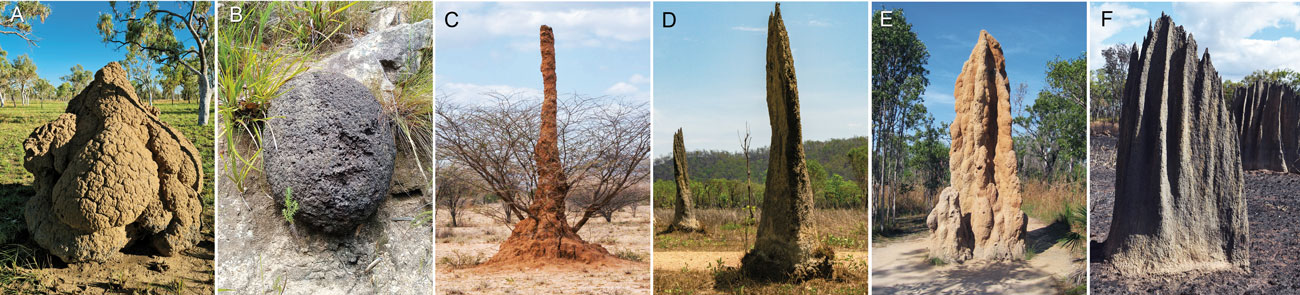

On the outside, termite mounds can be divided into two categories: large fortresses that can be many meters tall, or small configurations that measure a few centimeters high (see figure above). Soil composition influences mound structure, so the final type of mound depends on the type of soil available locally.

And the structures are not static; termites are always remodeling. “When the temperature becomes really low, the structure of a large mound changes from an elaborate, cathedral shape to a dome shape,” Karibi-Botoye says. “The termites change the structure to adapt to changing temperatures.”

N. F. Karibi-Botoye et al., Journal of the Royal Society Interface 22:20250263 (all images)

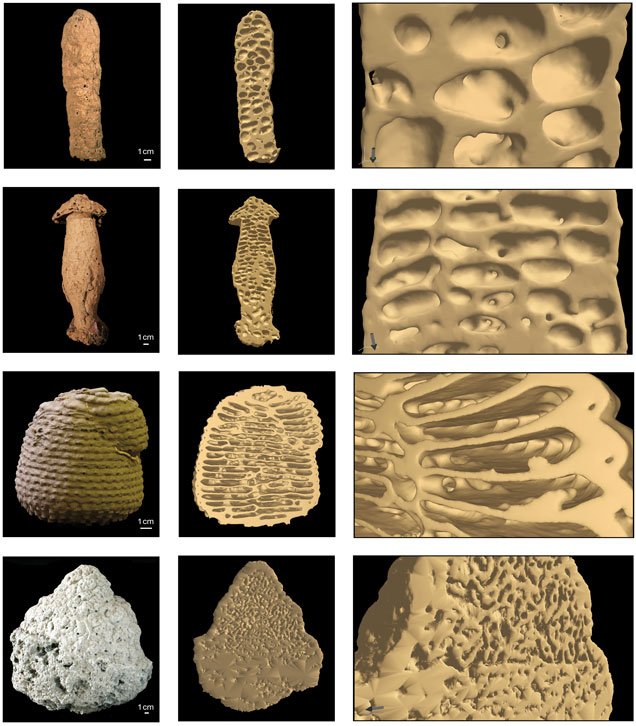

Karibi-Botoye and her colleagues collected several small termite mounds from different field sites (see figure above). Theraulaz and his team used a medical CT scanner to visualize the inner workings of the mounds at the millimeter scale, recording the holes in the outer wall and chambers. Next, Karibi-Botoye and her colleagues in Singh’s lab used an x-ray microtomography scanner, allowing them to see smaller features such as micropores in the walls. After incorporating the micrometer results into the millimeter outcomes, they had a multiscale view of the mounds they could use to do airflow simulations.

These simulations helped the researchers examine whether current theories of how ventilation occurs in termite mounds are accurate. For example, several years ago other scientists proposed that the Sun plays a role in the ventilation of large termite mounds. When the Sun heats up a termite mound during the day, the surface of the mound has a higher temperature than the inside of the mound. As the warmer air rises, it pulls cooler air from the inner part of the mound to the surface, where carbon dioxide is exchanged through the outer wall. In the evening, the reverse happens: The outer surface becomes cooler, and air in the inner mound is warmer. The colder air forces the warmer air from the inner mound to the surface and out of the mound. This process also removes carbon dioxide.

Such a system works in large mounds, but what about smaller nests that are a few centimeters in size? Theraulaz argues ventilation has to work differently because a mound needs to have a critical size to exhibit that air circulation.

“In the beginning, when the nest is small, the processes involved in ventilation are different from those that happen later, when the colony enlarges the nest,” Theraulaz says. “For smaller nests, ventilation is by diffusion.”

BBC Earth

Termite building behavior, the team says, is regulated by both temperature and carbon dioxide levels. When mound size increases, the variability of carbon dioxide increases, which affects how termites build and reshape the nest. And reaction to different local conditions explains why the internal structures of small nests are different from large mounds, even if they are built by the same species.

Singh adds that the knowledge they had before they started using this combined technique was mostly from models and fieldwork. Now, they can compare fieldwork measurements with simulations to produce a fundamental understanding of termite mounds.

“We are doing simulation modeling for the first time on an actual structure,” Singh says. “The group started from scratch and are filling the gaps in a way that has not been done previously. I think this is really important because if we start building prototypes, we need the concepts right."

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.