Searching for Great Adventures

By Tony Rothman

There are an infinite number of inspirational scientific journeys awaiting out there, and not all of them require looking up.

There are an infinite number of inspirational scientific journeys awaiting out there, and not all of them require looking up.

DOI: 10.1511/2014.106.10

In July 1969 I spent 14 straight hours glued in front of not one but two televisions, so as not to miss a moment of the first lunar landing. My captivation was more than that of a scientifically inclined youngster; it was a Great Adventure shared with hundreds of millions of other people around the world. Due to the inspiration provided by the space program, an overdose of speculative fiction, and a physicist parent, I ended up pursuing a career in relativity and cosmology. Yet 40 years down the road, when NASA announces the latest discovery of water on (your favorite planetary body here), my first response is an involuntary shudder.

The Pavlovian reflex has arisen over the decades largely in reaction to NASA’s propensity for outrageous hype. A crucial instance for me took place in 1994, when Daniel Goldin, then NASA’s chief administrator, advocated the construction of a lunar-based observatory to search for Earth-like planets on the grounds that their discovery “might inspire us to invent warp drives.” At that moment I parted universes with NASA. Mine was and remains ruled by physics; Goldin’s was evidently ruled by Star Trek. I felt ashamed that one of the country’s top scientific leaders could propose violating the laws of nature as an argument to secure funding.

A more public embarrassment followed two years later, when NASA unleashed a scientific derecho over the country by announcing meteoric evidence for life on Mars. So inflated were the claims of microscopic fossils, announced with velvet and trumpets at a Washington, D.C., press conference, that every one of my colleagues immediately assumed it was a bid for money. The squall passed as quickly as the claims were discredited, but it confirmed what was by then blindingly clear: NASA’s raison d’être in the post-Apollo era is the discovery of extraterrestrial life. That motivation is inherently problematic. There is fantasy, there is adventure, and there is science, and we have never learned where one leaves off and the others begin.

NASA uncomfortably straddles all three terrains, and yet space boosters have had remarkable success in monopolizing the concept of Great Adventure. Doubling NASA’s budget, according to my friend Neil DeGrasse Tyson, the director of the Hayden Planetarium, would “transform the country from a sullen, dispirited nation, weary of economic struggle, to one where it has reclaimed its 20th century birthright to dream of tomorrow.” Neil’s words could easily have come, with slightly more sobriety, from the lunch-table conversations at the National Radio Astronomy Observatory in West Virginia, where I worked for a few summers in the 1970s and where the discovery of extraterrestrial life was viewed as potentially the most important event in the history of humankind.

The discovery of extraterrestrial life would surely have profound philosophical effects. Nevertheless, I recoil at the notion that space is not just the final frontier but the only frontier. It is not entirely clear whether the relative banishment of other endeavors to the shadows is due to the spotlight NASA’s agency-sized publicity budget casts on an already romantic cause, or due to the dismal failure of proponents of those other undertakings to adequately promote them. What is clear is that the concept of adventure must be broadened, and that requires more distinctly perceiving the indistinct borders separating fantasy, hype, starry-eyed romanticism, and science.

Who defines a Great Adventure? If to a scientist, science itself is the adventure, one need only cast an eye back on the ill-fated Superconducting Super Collider—the giant particle accelerator that would have discovered the Higgs boson a decade ago had it been built in Texas as planned—to recall that such an attitude is far from universally shared. The Super Collider had many detractors within the scientific community, but none doubted that its mission was scientific. Not so for the politicians.

Physicist Steven Weinberg recollects that at one House of Representatives hearing, a congressman confessed that he could understand how the International Space Station would help us learn about the universe, but he couldn’t understand how the same applied to the Super Collider. When the question “What will it find?” met no response other than “Higgs boson,” the $8 billion Super Collider was canceled in favor of the largely science-free Space Station, which has ended up costing an order of magnitude more. (Earlier that year, physicist Leon Lederman branded the Higgs boson as the “God particle,” but too late.) That the Super Collider lacked government contractors beholden to it in every state was certainly not incidental to the outcome.

In any case, high scientific return is apparently not sufficient to help Congress pinpoint a Great Adventure. The United States also declined to become a major player in the European Union’s Large Hadron Collider, which did discover the Higgs boson and revealed something fundamental about the universe. Lawmakers have failed as well to find inspiration in another project that is potentially as practical as the Super Collider was not: ITER. Currently under construction by the EU and a half-dozen other countries in Cadarache, France, ITER is a giant experimental device whose aim is to create the world’s first self-sustaining nuclear fusion reaction. ITER is over budget and behind schedule, and there is no guarantee that fusion will ever prove to be economically viable. For all that, one might think that the idea of creating a star on Earth, and the prospect of limitless energy, should fire the world’s imagination.

Yet when ITER was proposed, America’s first action was to pull out of the project. The country eventually rejoined, as a minor player, and Congress continues to make noises about zeroing the U.S. ITER budget. Energy sustainability in general has inspired scientists and engineers far more than it has politicians and the public, both of whom—whether because of fear of fracking or the influence of Big Oil—regard energy as less romantic than necessary. China and South Korea have both intimated that they will go the fusion path alone should ITER fail, but in the United States, a sustainable energy future has not attained the mantle of Great Adventure.

Among the sciences, cosmology has perhaps come closest to attaining Great Adventure status. It sells magazines, editors assure me, and some billions have been spent on cosmological probes like WMAP and Planck. To many cosmologists, myself included, there is deep romance in the adventure. On a psychological level, the field may even serve as a substitute religion for doubters and nonbelievers—witness the many “faces of God” metaphors cosmologists routinely trot out. The public’s interest (and, according to legend, certain lawmakers who want to find the Creator) in cosmology is undeniably stimulated by the God question.

But cosmology is first and foremost a science, one which requires higher mathematics, exact observations, and sophisticated data reduction. At the same time, though, it is not space exploration: One of the triumphs of 20th-century science is that we managed to learn so much about the universe without going anywhere. Thus, what cosmology has gained over the years as a science, it has lost in intelligibility to the public, and it does seem that if Congress and the public view cosmology as a Great Adventure, they do so largely for the wrong reasons.

Much of this confused view of Great Adventure derives from a peculiarly American demand for “useful romance.” The obsession should surprise no one in a country founded on Manifest Destiny—a useful romance if ever there was one—and where Thomas Edison is a far greater hero than J. Willard Gibbs. The self- contradictory desire for both utility and romance is reflected in media coverage of science. It’s a fair bet that All Things Considered has devoted an order of magnitude more air time to string theory than to combustion physics. On the other hand, regardless of whether the topic is the Higgs boson or the mathematics of ponytails, any scientist facing a reporter knows there is no escape, none, from: “What are the practical applications?”

Reporters are almost instinctively drawn to the “woo factor.” At least that is what they called it at Discover magazine, where the editor-in-chief deemed it advisable to include a woo-factor article in every issue. I know this first hand because for a year in the 1980s I was the magazine’s designated Woo-Master. But the “What are the practical applications?” guillotine, dropping at the close of every science interview, shows that if we take inspiration from the far-out, the cosmological, and the spiritual, we nevertheless demand that “woo” raise our standard of living. In other words, we demand spinoffs.

NASA itself publishes a journal called Spinoffs, and claims credit for more than 1,600 practical inventions, though not Tang or Teflon. But the space agency is hardly alone in enlisting practical results to support the scientific cause. In a recent interview, Robbert Dijkgraaf, director of Princeton’s Institute for Advanced Study, promoted basic research on the grounds that 50 percent of all industry is now based on quantum mechanics, which a century ago was viewed as infinitely stranger than practical. (This figure presumably reflects the percentage of the economy involving semiconductors. By the same argument one could claim that 100 percent of modern industry is based on electricity and magnetism—even though the founders of the communication and power industries understood little of their underlying physics.)

Mathematics is one of the greatest adventures. The mathematical universe is vast, fully infinite. But truly, the directions to adventure are myriad.

The appeal to spinoffs demonstrates that the argument from inspiration has never entirely persuaded the American public, lawmakers, or scientists themselves. Yes, the Apollo mission did inspire many Americans, but our rose-colored glasses should not tint away the fact that it wasn’t called the “space race” for nothing: The effort to beat the Soviets to the moon jostled with adventure and completely eclipsed a sensible scientific program. Let us also not forget that Apollo’s huge budget divided the nation into camps pro and con, and that within a few years of Neil Armstrong’s first steps, moon landings were met by a yawn.

Arguments over trickle-down science, a direct product of our demand for practical romance, are more complex than they are generally treated in public discourse. Some science always pays off in the long run, but most doesn’t, and the trouble is that one can never predict which discovery will change civilization. Advocates of applied research argue, often pointing to the Manhattan Project or Bell Labs, that such an approach has a better track record of producing results than the random walk of pure science. The debate is not trivial, but in the present context, they miss the mark. If we seek inspiration, wherefore spinoffs? If we demand spinoffs, wherefore inspiration?

No natural law compels the adoption of such an oxymoronic attitude, and it would be wise to change our attitudes and expectations. Most scientists may work in applied fields, but a substantial number pursue “curiosity-driven science.” Lawmakers should pronounce those words without derision, and we would do well to rethink the current model for research grant applications—a model that seems to require knowing the outcome of a program in advance, in contravention of the old joke: “If we knew what it was we were doing, it would not be called research, would it?” Nevertheless, one congressional leader recently drafted a bill requiring that the National Science Foundation fund only research that would manifestly “advance the national health, prosperity, or welfare.”

Reporters and lawmakers should recognize that in pursuing their passions, scientists and mathematicians are not unlike artists, at least until the need for funding rises. (A Large Hadron Collider admittedly costs more than even Van Gogh’s Sunflowers and demands more justification.) At the same time, the potential practical applications of an endeavor should not damn it to the realm of the mundane. We take for granted that flipping a switch produces light, but 150 years ago the same act was a revelation. That our power grid functions at all strikes me to this day as a miracle. Constructing a national smart grid should be viewed as a Great Adventure.

The 19th-century American artist Thomas Cole once painted a series entitled “The Voyage of Life.” In the first canvas, Childhood, the infant voyager sets off on a skiff down a stream surrounded by lush overgrowth, the far landscape hidden from his naive eyes. In the second panel, Youth, the stream has widened to reveal majestic castles floating above distant, beckoning horizons. In the third panel, Manhood, darkness colors the scene and our hero holds his hands in supplication as his skiff approaches swirling rapids. In the fourth panel, Old Age, well, you get the idea …

As romantic as Cole’s allegory strikes us at a distance of 200 years, it holds much truth. With the onset of adulthood, expectations diminish, adventures become smaller. Be that as it may, I see adventures everywhere, even more than I did as a youth gazing only skyward at far pavilions and moon landings.

Twenty years ago, plastic grocery bags routinely tore at the slightest provocation. Now, they display the character of flexible steel. They are a wonder of modern materials science, a subject lying at the intersection of physics, chemistry, and engineering. A 1-farad capacitor used to be a monstrous thing (and this former boy scientist remembers collecting such beasts from junkyards: two feet tall and 50 pounds). Due to recent advances in nanotechnology, in our freshman lab this year we employed 1-farad capacitors the size of a thumb. Surely, the development of such devices, and the novel materials that make them possible, is a Great Adventure.

At the artistic end, mathematics is one of the greatest adventures. The mathematical universe is vast, larger than the physical universe, fully infinite. Unfortunately, it is also, as German poet Hans Magnus put it, “a blind spot in our culture—alien territory, in which only the elite, the initiated few have managed to entrench themselves.” We hear vanishingly few segments about mathematics on NPR, much less Fox News, and those few are invariably capped by the demand for practical romance.

To be sure, the quantity of curiosity- driven mathematical explorations, amusements, and games that turned out to bear enormous practical fruit is astounding: number theory and cryptology, quaternions and satellite pointing, topology and the delivery patterns of FedEx. Nevertheless, one shouldn’t need to resort to counting mathematical spinoffs, even if their numbers exceed NASA’s. The very infinity of the terrain should inspire. Unfortunately, mathematicians are a particularly inarticulate species. If they do not wish to stand perpetually shouting for attention from the sidelines, that must change.

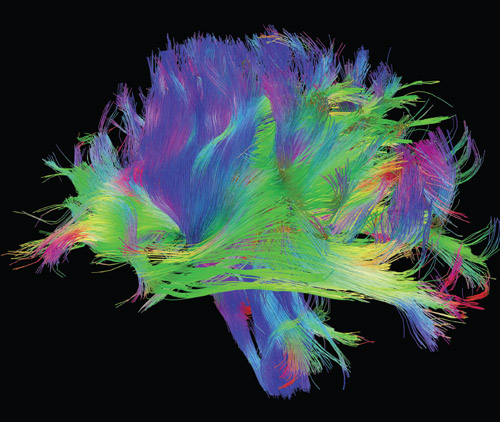

Because I am a mathematically inclined physicist, my perception of great adventures tends to be biased in that direction, but truly the directions are myriad. President Barack Obama, in announcing the 2013 Brain Research through Advancing Neurotechnologies initiative, recognized that the exploration of the human brain is a Great Adventure. With its hundred billion neurons—about the same number as stars in the Milky Way—and a quadrillion synapses, the brain presents one of the most expansive terrains for new discoveries. Looking outward, we cannot fail to mention the oceans. As marine researchers regularly proclaim, we know more about the surface of the moon than about the ocean floor. Exploring there is not only a path to inspiration; it is also of crucial importance to the survival of the planet. And then, of course, there are origin-of-life studies. I do not mean the mere identification of Earth-like planets but an understanding of the pathways to the first cell here on terra firma.

As a scientist who has spent his career tangling with fundamental issues and never getting to the bottom of any of them, I long ago came to the realization that I would be happy to understand just one thing in nature. My embrace of a micro-goal may indicate that I have passed out of Thomas Cole’s second stage of life, but it may also be that civilization itself has voyaged past Youth. In our epoch it is unlikely that any single adventure will lift the spirit of a nation, as the moon race once did, for the simple reason that society has become too diverse to obsess over just one inspiration. I am not alarmed; my muses stand everywhere, waiting to be acknowledged.

Sooner or later there will be a colony on Mars. That is gratifying and inspiring. But a colony on the ocean floor would be equally gratifying and inspiring. The creation of an effective malaria vaccine, a molecular computer, a proof of the Riemann hypothesis….

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.