Revolutionary Minds

By Susan Solomon, John S. Daniel, Daniel L. Druckenbrod

Thomas Jefferson and James Madison participated in a small "revolution" against British weather-monitoring practices

Thomas Jefferson and James Madison participated in a small "revolution" against British weather-monitoring practices

DOI: 10.1511/2007.67.430

In 1790, Thomas Jefferson began his tenure as America's first Secretary of State in the cabinet of George Washington. In this role, he would wrestle with a host of issues facing the struggling new republic, including such weighty matters as neutrality or engagement should England undertake a war of conquest with Spain for Louisiana. But politics and government represented only one side of the life of the man who would become known as one of America's most cerebral presidents.

Photograph by Susan Solomon.

Among other pursuits, Jefferson had an abiding interest in science, including the science of weather and climate. As Jefferson took up the office of Secretary of State, he wrote to his son-in-law about his difficulties in finding a place to live, which were caused by an unusual, exacting and quite personal requirement:

I have not begun my meteorological diary; because I have not yet removed to the house I have taken. I remove tomorrow: but as far as I can judge from its aspects there will not be one position to be had for the thermometer free from the influence of the sun both morning & evening. However, as I go into it, only till I can get a better, I shall hope ere long to find a less objectionable situation. (TJ to Thomas Mann Randolph, May 30, 1790)

Jefferson's interest in meteorology was linked in part to its role in the plantation farming that was both his heritage and his livelihood. He apparently began taking daily data himself while still a student at Williamsburg, perhaps inspired to do so by his friendship with then-governor of the colony Francis Fauquier, who is believed to have followed a similar practice. Throughout his life, Jefferson corresponded widely with other weather observers, exchanging both data and musings:

Soon after receiving your meteorological diary, I received one of Quebec; and was struck with the comparison between -32 & +19-3/4 the lowest depression of the thermometer at Quebec & the Natchez (Mississippi). I have often wondered that any human being should live in a cold country who can find room in a warm one. I have no doubt but that cold is the source of more sufferance to all animal nature than hunger, thirst, sickness, & all the other pains of life & of death itself put together. (TJ to William Dunbar, January 12, 1801)

Jefferson's study of meteorology was also motivated in part by national pride, tracing to his profound displeasure with the work of one of the most distinguished naturalists of his day: French scientist Georges-Louis Leclerc, the Comte de Buffon. Buffon expressed the view that the climates of the colonies in America were degenerative, "that nature is less active, less energetic on one side of the globe than she is on the other" (Jefferson's translation), and asserted that climate in turn led to smaller and less diverse plant and animal life in the New World as compared to the Old. By way of counter-evidence, on October 1, 1787, a proud Jefferson sent Buffon the skeleton of a moose along with written descriptions of the massive antlers such animals often possessed, expressing the hope that it "may have the merit of adding anything new to the treasures of nature which have so fortunately come under your observation." Jefferson also vigorously disputed Buffon's claim in his own book, Notes on the State of Virginia, arguing for the need for more data and "a suspension of opinion until we are better informed" as to issues such as differences in temperature and humidity, as well as the effects of climatic differences on flora and fauna.

Jefferson not only took measurements himself but also encouraged others to do so, including his close friend and political ally, James Madison. The partnership between Madison and Jefferson as two leading figures in the political events of the American Revolution is well known and amply illustrated by correspondence that includes reflections on early drafts of the Constitution. Jefferson wrote to Madison in 1787 to express his view of the pressing need for "… a bill of rights providing clearly & without the aid of sophisms for freedom of religion, freedom of the press, protection against standing armies, restriction against monopolies, the eternal & unremitting force of the habeas corpus laws, and trials by jury in all matters of fact triable by the laws of the land…." It was just a few years before this that Jefferson made quite a different request to Madison:

I wish you had a thermometer … [to] observe at Sunrise & at 4 o'clock p.m. which are the coldest & warmest points of the day. If you could observe at the same time it would shew the difference between going North & Northwest on this continent. (TJ to JM, February 20, 1784)

David Schneider and Barbara Aulicino

The request was more demanding than it might appear. High-quality instruments were very difficult to come by in the late 18th century. Jefferson spared few expenses in pursuit of his interests and seldom purchased anything but the very best in wines, books and scientific instruments. In July of 1776, just as the Declaration of Independence on which he had labored was being signed, Jefferson purchased a Sparhawk thermometer for 3 pounds, 15 shillings—equivalent to at least several hundred dollars today. Madison acquired a thermometer as his friend requested, and he and his family recorded a series of high-quality daily measurements that spanned about 18 years at their Montpelier plantation near Orange, Virginia. (Madison's father's handwriting appears especially often in the record, along with that of the future president and others thought to be his brothers).

Jefferson and his circle of contacts fully appreciated the need for care and attention to calibration. One correspondent wrote that it was important to "ascertain the accuracy of the division by plunging it in boiling water," suggesting that Jefferson and his associates were well aware of the standards prescribing this procedure that had been established by a commission of the Royal Society led by Henry Cavendish.

In 1723, the Royal Society set out recommendations for instrument placement in a paper published by James Jurin, its Secretary: "We judge the most suitable position for a thermometer to be in a closed room, oriented to the North, where a fire is rarely, if ever lit." The Society also invited observers to publish such results in its Philosophical Transactions. Considerable debate about instrument placement ensued in the Philosophical Transactions and elsewhere, with a number of weather observers (particularly in continental Europe) arguing that outdoor measurements would be more useful. Although the need to keep instruments out of the sun was evident, the role of radiative exchange from all sources, including the heat sink of the sky and the emitting temperature of the ground or other nearby objects, was not yet understood. It was not until the period from about 1840 to 1870 that the dual problems of retaining air flow while shielding from the cooling and warming effects of radiation of the surroundings on the air thermometer were managed through the use of louvered boxes or sheds (see Figure 1 for a current system). A well-calibrated indoor instrument might still obtain an accurate daily or multi-daily mean, albeit one with a variable thermal lag induced by its surroundings.

In continental Europe, outdoor measurements, as well as some indoor and outdoor observations, were carried out in a few well-organized observing networks as early as the 1770s, but a number of early observers worldwide dutifully did as the prestigious Royal Society prescribed for many decades, making indoor measurements a major obstacle to the interpretation of many key early meteorological series such as those interpreted by Dario Camuffo, and by Gordon Manley and his colleagues.

Madison informed Jefferson that the temperature on April 27, 1785, "on the second floor and the NW side of the house was on the 24th at 4 o'clock at 77°[F]." Jefferson's notes, for example in December 1802 and February 1803, indicate that data were being taken in a bedroom with "no fire." Thus both men took some data following the Royal Society indoor method, but neither persisted in that mode throughout their lives.

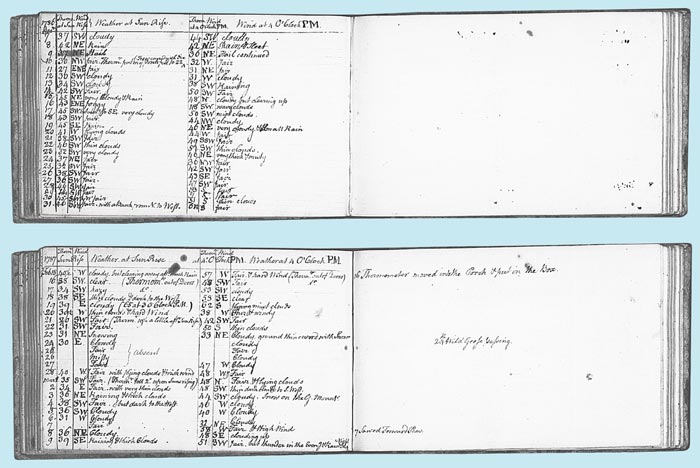

Madison appears to have been the first to probe other options. The future president left his home to attend the constitutional convention in late January 1787, but it is clear that he and his family began to wonder about instrument placement shortly before his departure. On December 10, 1786, the Madison family weather diary (see Figure 7) noted that trees were covered in ice and that the thermometer dropped from 30 degrees Fahrenheit to 22 when put "on the porch." On February 16, 1787, the thermometer was moved to the porch and "put in the Box." This arrangement represented a key step forward, beginning to resemble that employed in modern observations.

Barbara Aulicino

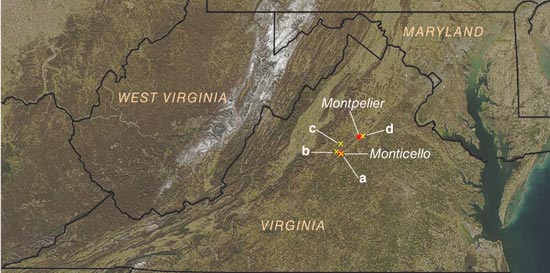

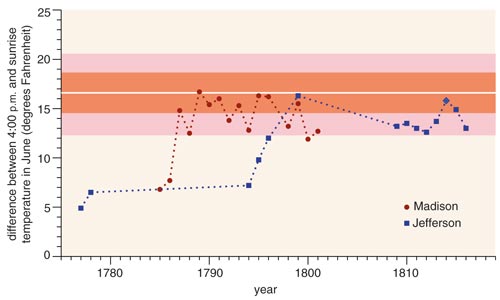

Figure 2 shows the locations of the Madison Montpelier plantation, Jefferson's Monticello and the closest nearby modern stations where high-quality daily weather records have been routinely kept for decades. Figure 3 compares the difference between 4:00 p.m. and sunrise data observed by Jefferson as well as by Madison for the month of June, to the average values of hourly data from Charlottesville (the nearby modern station that has the most complete hourly series of data).

Illustration from the Library of Congress. Photograph at upper right by Susan Solomon and at lower right by Mary Anne Sullivan.

The siting of Madison's instrument inside the home before 1787 (irrespective of the lighting of fire) clearly greatly reduced the morning-to-afternoon changes in the data compared to outdoor values: The indoor morning data were much warmer than the outside air temperature, and the afternoon data decidedly cooler, so that the range in temperature through the course of the day was greatly reduced by the thermal lag of the home.

After noticing that the data were inconsistent with the occurrence of ice and taking the bold step of moving the instrument outdoors to the box on the porch in 1787, Madison's morning and afternoon observations are dramatically different, and the morning-to-afternoon changes immediately approach modern outdoor data. Thus, in meteorology as in politics, Madison was among the American founders of measures that represented a revolution against British practices.

The Montpelier Foundation

In the late 1780s, Madison was engaged in the struggle for a Bill of Rights and in decisions over the positioning of his thermometer, while Jefferson was in France, serving as what might today be called ambassador. Jefferson negotiated a close relationship with France as the separation of the newly established United States from Britain took shape, and he was a party to the events that led to the French Revolution. Despite his strong interest in European science, he appears to have been unaware that systematic outdoor meteorological measurements were being collected in France and Germany, organized through the Société royale de médicin and the Societas Meteorological Palatina (Mannheim Meteorological Society). Jefferson continued to take daily measurements of temperature following the Royal Society indoor approach throughout the 1780s and 1790s, as indicated in a January 28, 1790, letter from his personal secretary William Short noting that his "little thermometer which was in the passage is now in the alcove at the foot of your bed."

Jefferson, like Madison, also appears to have begun considering other approaches in the 1780s, but his ideas differed from those of the Madison clan. On December 10, 1788, he wrote to an instrument maker named William Jones to commission construction of two thermometers "graduated from boiling water down to the congelation of spirits of wine … they are intended to be hung on the outside of a glass window, with the face of the plate next to the window so that it may be seen without opening the window."

Jefferson's imagination led to a number of inventions, including a new type of plow offering less resistance and greater efficiency. He had an eye for and a deep appreciation of style, as well as a craftsman's approach to substance and utility. Nowhere are these more apparent than in his many unique designs of his home at Monticello, and positioning of his thermometer directly on a window for easy viewing would have been consistent with a number of other innovations Jefferson built into the dramatic home. The Great Clock could also be viewed from both inside and outside, as could the dial of the weathervane (Figure 4). These indoor-outdoor design features may have been considered elegant by Jefferson, but placement of the thermometer against the window of the stately and massive house can certainly be expected to have affected the data. Some of the brick walls that were made from Monticello's own clay were more than two feet thick, yielding a formidable thermal lag in temperature measurements.

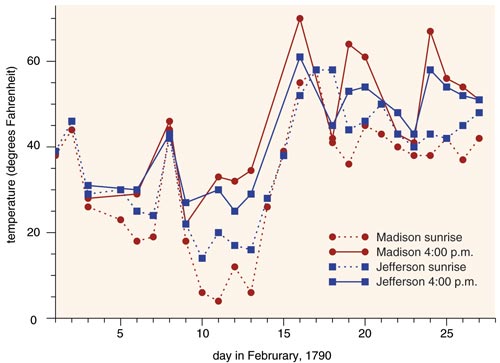

In early 1790, Jefferson returned to the United States, spending a few months at his home at Monticello and taking daily meteorological data as he always did. These provided the first chance for direct comparison of simultaneous data from Monticello to those at the Madison plantation just 21 miles away. Jefferson was not specific about the location of his instrument while taking these data. He found to his apparent dismay that there were great differences in the two measurement series. He wrote to his son-in-law about the large discrepancy, trying to explain it by the change in elevation between the two, all the while noting that even in his own view this explanation seemed far-fetched:

You know that during my short stay at Monticello I kept a diary of the weather. Mr. Madison has just received one, comprehending the same period, kept at his father's in Orange. The hours of observation were the same, and he has the fullest confidence in the accuracy of the observer. All the morning observations in Orange are lower than those of Monticello, from one to, I believe, 15 or 16 degrees: the afternoon observations are near as much higher than those of Monticello. Nor will the variations permit us to ascribe them to any supposed irregularities in either tube, because, in that case, at the same point the variations would always be the same, which it is not. You have often been sensible that in the afternoon, or rather evening, the air has become warmer in ascending the mountain. The same is true in the morning. This might account for a higher station of the mercury in the morning observations at Monticello. Again when the air is equally dry in the lower & higher situations, which may be supposed the case in the warmest part of the day, the mercury should be lower on the latter, because, all other circumstances the same, the nearer the common surface the warmer the air. So that on a mountain it ought really to be warmer in the morning & cooler in the heat of the day than on the common plain; but not in so great a degree as these observations indicate. As soon as I am well enough I intend to examine them more accurately" (TJ to Thomas Mann Randolph, May 30, 1790)

Barbara Aulicino

Figure 6 shows the morning and evening observations taken in February 1790 at Monticello and Montpelier that were the subject of Jefferson's consternation. Elevation does not explain the differences, as despite being referred to by Jefferson as a "mountain," Monticello is only a few hundred feet higher than Montpelier. Jefferson's measurements reflect the clear influence of the thermal lag of his home, whereas Madison had already moved his instrument to the box on the porch by then and was therefore taking data with a morning-to-afternoon range in broad agreement with modern outdoor data as shown in Figure 3.

Many historians have puzzled over Jefferson's early observations and have wondered for example whether the apparently rather mild temperatures he recorded for July 4, 1776, are consistent with other suggestions that the Declaration of Independence was signed during a sweltering week. Figure 6 illustrates that the indoor bias was often more than 10 degrees. If the placement of Jefferson's thermometer in Philadelphia were similar to that at Monticello, then the outdoor conditions during the historic week of July 4, 1776, were virtually certain to have been much warmer than those recorded at that time by the man who had led the crafting of the document that would become an icon of American government.

Jefferson's observations through much of the 1790s largely suggest an indoor (or perhaps window-mounted) bias. Monticello was also under frequent remodeling and construction over decades, with roofing and other changes throughout. The northeast portico (Figure 4) took many years to complete, and in the late 1790s it became the location for the thermometer. But Jefferson doubted the data obtained there, writing in his log book that "all the thermometrical observations of the year 1798 and those of 1799 to June 17 inclusive are to be rejected. During that period my thermometer had been placed in the N.E. portico, newly built, and it was not until Jun 17 … that I discovered it to be artificially heated, probably by the mound of earth in it." Figure 3 makes it evident that the morning-to-afternoon differences for June of 1799 were actually more representative of the outdoors than his earlier data rather than less so. Although he did not realize it, he was not measuring the effect of an "artificially heated" mound but more likely a genuine improvement afforded by better ventilation of his instrument. His friend Madison had much earlier written a letter that should have provided a clue:

The most remarkable occurrence of late date here was the excessive heat on Sunday the first instant. At two Oclock the thermometer in its ordinary position was at 99°[°F]. At four it had got up to 103°. On being taken into the passage the coolest part of the House it stood at the former hour at 97° and at the latter at 98°.… (JM to TJ, July 5, 1792)

Images from the American Philosophical Society.

These remarks about instrument positioning demonstrate that not only his family but also Madison himself were quite engaged with the issue of thermometer location. But Madison's remarks went unanswered by Jefferson. Further, it is not clear whether Jefferson ever expressed his quandary over the differences in their observations directly to Madison.

History leaves no doubt that Jefferson and Madison were the closest of friends. But it would be natural for a Virginian aristocrat to decline to criticize data obtained by a friend at considerable time and expense, particularly when these observations had been acquired in direct response to a request. Their correspondence during the 1790s also makes clear that both men were engrossed in matters of far greater urgency and national importance, including the deepening rift with Alexander Hamilton. Jefferson described his conflicts with Hamilton in Washington's cabinet as akin to "cocks in a pit."

Although it seems remarkable in view of the other demands on him at the time, Jefferson continued his daily sunrise and 4:00 p.m. measurements of temperature as he assumed the presidency in 1801, after a contentious election against John Adams that was decided by Congress.Even more remarkable is the fact that it was while holding the nation's highest office that Jefferson finally began to probe the issue of thermometer exposure, through measurements in which he recorded data taken with open versus closed windows. In early 1803 while at the White House, just as he dispatched Monroe to France to negotiate with Napoleon for the Louisiana purchase (which ultimately would be viewed as one of the major accomplishments of his presidency), he took a series of measurements outside, inside and inside with an open window, noting the "great difference in the thermometer when accompanied by o.w." (open window). The data taken after about this time consistently display more plausible diurnal ranges, suggesting that it was after this series of observations that Jefferson began systematically exposing his instrument far better than he had previously done.

Barbara Aulicino

Although it is not known whether they ever discussed it, in 1803 Jefferson joined Madison in opting for a quiet revolution, choosing to measure temperature outdoors instead of in rooms without a fire as suggested by Britain's Royal Society.

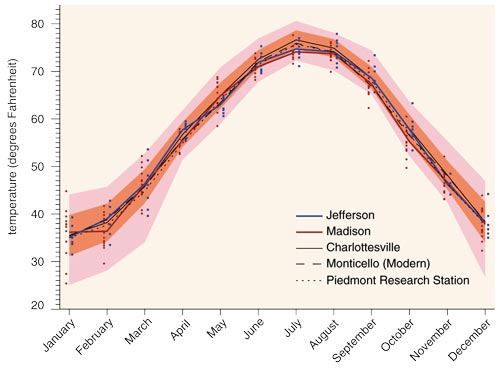

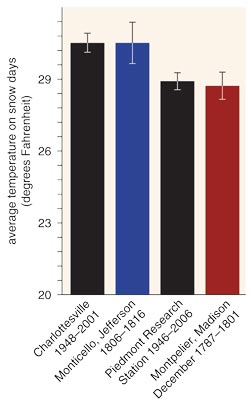

The averages of Madison's measurements at Montpelier and Jefferson's at Monticello for each available month of the year (outdoor only) are compared to modern data in Figure 8. The graph shows excellent agreement of the historical and modern data to within a few degrees, attesting to the general quality of the work done by the various Madison family observers as well as by Jefferson, including their own calibration corrections using boiling water.

Barbara Aulicino

An independent check on the accuracy of the historic data is provided by comparison of the temperatures on days with snowfall to modern measurements at sites nearby. Snow falls on days typically characterized by specific types of meteorological conditions, and the corresponding characteristic temperatures at the two modern Virginia stations that are closest to the Madison and Jefferson plantations match the historical data well as shown in Figure 8, strongly supporting the accuracy of both instruments. Similar comparisons were used by Gordon Manley in establishing the long-term averages of Central England historical records of temperature.

Is Virginia warmer today than it was a few hundred years ago? Climate studies suggest that human activities have caused a globally averaged warming of the order of 1.5 degrees Fahrenheit due mainly to emissions of greenhouse gases, mostly in the 20th century. Determination of such changes requires a very high level of both precision and accuracy, and care must be exercised in interpreting local data, which can be influenced by such factors as land use and nearby aerosol pollution. A great deal of further analysis beyond the scope of the present work would be needed to determine whether the Jefferson or Madison observations may be of scientific value in the context of the modern challenge of global warming, but it is interesting that the Madison record (which is far more complete than that of Jefferson) is not inconsistent with cooler conditions in the late 18th century, particularly in summer.

Jefferson continued to deal not only with political exchanges with France but also with scholarly ones. In 1805 he wrote to the Comte de Volney, who had written a book about America, including its climate. Volney's work was decidedly less negative than that of his countryman Buffon, and Jefferson wrote: "I have read it, and with great satisfaction." Jefferson also commented on the differences in extreme temperatures between Europe and the United States, noting the importance of adaptation in determining the responses to extremes:

In no case, perhaps, does habit attach our choice or judgment more than in climate.… The changes between heat and cold in America, are greater and more frequent, and the extremes comprehend a greater scale on the thermometer in America than in Europe. Habit, however, prevents these from affecting us more than the smaller changes of Europe affect the European. (TJ to Volney, Feb. 8, 1805)

Both Madison and Jefferson have left confused legacies that have confounded attempts at simple descriptions. Both decried slavery in some of their writings, yet both owned slaves throughout their lives and declined to free them at their deaths. Both embraced ideals that today would be viewed as a mixture of liberal and conservative. Understanding their 18th century characters on a human level will likely continue to challenge people of the 21st century and beyond. But the stark numbers of their meteorological records add a different and objective dimension to their remarkable legacies—and open a window into their revolutionary minds.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.