This Article From Issue

November-December 2016

Volume 104, Number 6

Page 338

DOI: 10.1511/2016.123.338

The role of genetic diversity in extinctions appeared to be well understood—until recently, when data on one of the cutest endangered species were studied. These dainty creatures have big eyes, fluffy fur coats, and no fear of humans. They are Channel Island foxes, Urocyon littoralis, and they live only on six of the eight Channel Islands off the California coast. Each island has its own distinct subspecies; they have been on those islands for about 7,100 years.

In 2004, population levels were so low on four of the islands that the foxes were placed on the U.S. Endangered Species list. To my surprise, on August 11, 2016, three of the fox subspecies were removed from the U.S. Endangered Species list. The fourth population is increasing: a textbook example of the rescue and recovery of an endangered subspecies. Now there are more than 6,000 total Channel Island foxes.

Conservation measures rarely work so well or so fast. The Channel Island fox case involved several complex factors that led to their near-extinction and to their recovery.

Photograph by Lyndal Laughrin, courtesy of UCLA Institute for Quantitative and Computational Biosciences Collaboratory.

One danger to these foxes lay in other species introduced by humans—intentionally or by accident—that carried disease or parasites or drew new predators that expanded their prey repertoire. Ironically, the foxes themselves were probably originally carried to the islands by Chumash Indians, who lived there and considered the foxes sacred.

In the 1990s, drought, parasites, and disease brought in by a stowaway raccoon, and predation by golden eagles, triggered the drastic population crashes that led to the foxes’ endangered status. Elimination of nonnative livestock and feral animals, replacement of invasive plants with native ones, and capturing and translocating golden eagles (which had been drawn to the islands by livestock carcasses), stabilized populations. Foxes were also vaccinated against introduced canine distemper virus. While these human-caused problems were solved or removed, foxes were bred in captivity and then returned to their home islands.

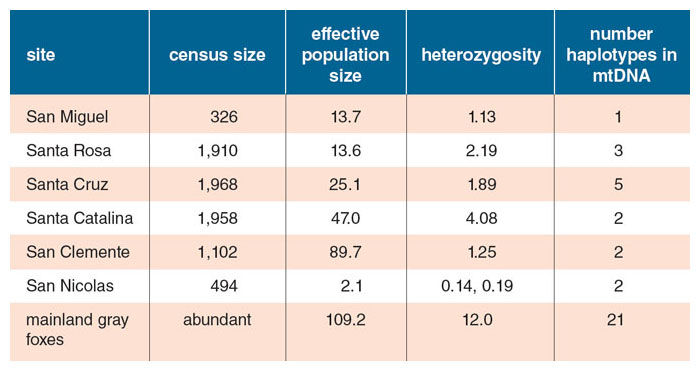

Comprehensive whole genome studies of nuclear DNA from the islands’ foxes, performed by Jacqueline Robinson and her colleagues in the genetics laboratory of Robert K. Wayne at the University of California, Los Angeles, uncovered additional factors in the near-extinction of the species. What they found was startling. Genetic diversity was low, and sequences from the two foxes from San Nicolas were so similar as to be almost identical genetically. The group calls it genetic flatlining

“We find a dramatic reduction of genetic variation, far lower than most other animal species,” Robinson said. No other wild species is known to have more limited genetic variability. Was this the underlying cause for the crash in fox populations?

Perhaps, but there is no sign of genetic deformity or deleterious inbreeding among the San Nicolas foxes. The UCLA team used population modeling to show that small, isolated populations with limited genetic diversity might succeed for hundreds of years without negative consequences. They attribute the genetic flatlining on San Nicolas to some recent event, not to long-term inbreeding.

Comparisons of relatedness among populations has been studied using the foxes’ mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA)— maternally inherited DNA that mutates faster than nuclear DNA but is not recombined through meiosis, the form of cell division that produces reproductive cells. Their mtDNA also showed limited diversity. Courtney Hofman of the University of Maryland and her colleagues recently analyzed mtDNA on 159 foxes from all Channel Islands to look at the size of the founding populations. They concluded that the original founding population was extremely small, possibly only one pregnant fox. Further movement of foxes among the islands must have involved human transport followed by random genetic drift.

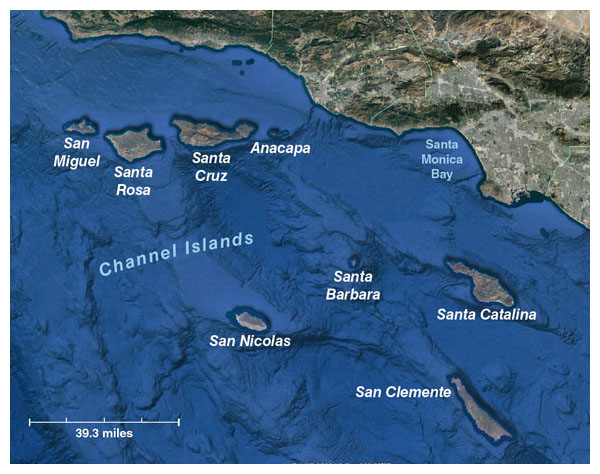

Map by Barbara Aulicino, Google Earth image.

The effort to intervene and save the Channel Island foxes was further complicated because the decision to act rested with several different groups that each bear the responsibility for monitoring and protecting the species in partnership with the others. Several of the northern Channel Islands are national parks, another one is owned by private individuals, and two are owned by the U.S. Navy. All stakeholders are bound by the stringent legal protections attached to endangered species. In general, the National Park Service favors a “no intervention” policy of management, yet they are explicitly charged with conserving “unimpaired many of the world’s most magnificent landscapes.... [and] prevent[ing] impairment of park resources and values….” The Channel Island foxes surely qualify as a unique and valuable resource.

Despite the dramatic population recovery on the northern Channel Islands, the struggle is not over yet. In 2014, the number of individuals on San Nicolas, where genetic diversity is lowest, had shrunk to 263 foxes. While populations on other islands were increasing, the San Nicolas fox population was diminishing from a high of 725 in 2008.

Ecologists often use estimates of effective breeding population—based on the diversity expressed in the genes of all individuals—as a measure of likelihood of extinction. W. Chris Funk of Colorado State University and his coworkers estimated that the 263 foxes on San Nicolas show so little genetic diversity that a breeding between any male and any female will yield basically the same genetic result. Their calculations yielded an astonishingly low estimate of effective breeding population: 2.1, with 2.0 being the lowest possible value for a sexually reproducing species.

For this reason, Funk and his colleagues advocate “supplementing a severely threatened subspecies with individuals from another subspecies.” By translocating foxes among the islands, the genetic diversity of each island will be increased, which should lessen the risk of extinction.

All data from J. A. Robinson et al., 2016; and C. A. Hofman et al., 2015; table by Barbara Aulicino.

On the other hand, such an action will destroy the uniqueness of each subspecies and probably the best documented example of long-term viability in a genetically limited population. Robinson and Wayne see no compelling need to step in because there is no sign of genetic deformity or deleterious inbreeding among the San Nicolas foxes. Possible dangers may include deaths by motor vehicle, perhaps the use of some new pesticide or rodenticide, or a factor yet to be discovered.

“I don’t favor attempting a genetic rescue because I don’t believe we are seeing a genetic problem,” Wayne explains. “Something else is going on. It is crucial that some biologists look at San Nicolas as soon as possible to find out what is causing this dramatic drop in population.”

When Wayne, Robinson, and their colleagues calculated the effective breeding population of the San Nicolas foxes over time, they found that it had been much higher, probably at least 64, for most of the past 500 years.

The Channel Island foxes have shown how successful conservation measures can be, when applied thoughtfully and promptly. But they also raise the possibility that we have misunderstood the importance of genetic diversity in long-term survival of endangered species. More work is urgently needed to discern what other factors might be at work among the Channel Island foxes.

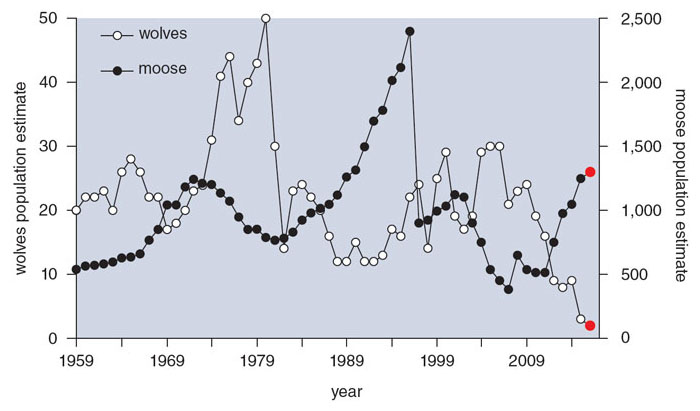

Wolf Diversity on Isle Royale

A similar debate over the role of human actions and genetic diversity in provoking or mitigating extinction threats is playing out in Michigan in the Isle Royale National Park. By 1930, with no predators on the island, the moose population had decimated the forest. Trees were mere nibbled stumps, and moose were starving. The island was named a national park in 1940 and has been free of nearly all human interference since then. For the next two decades, ecologists urged the National Park Service to introduce wolves to hold the moose population in check. Wolves solved the problem themselves by crossing an ice bridge to the island one winter. As predicted, an active wolf population seemed to balance out the moose and restore health to the ecosystem.

Rolf O. Peterson

But an outbreak of canine parvovirus in 1980—probably introduced by a dog brought onto the island against regulations—caused the wolf population to plummet. For the next 15 years, the moose population grew out of control, while the wolves became dangerously inbred; successful predation thus also diminished. In 1997, a male wolf crossed an ice bridge to the island, though such bridges had become increasingly rare with climate change. Within one wolf generation, the “Old Gray Guy,” as he became known, had sired so many offspring that 56 percent of the genes in the Isle Royale population could be traced back to this individual. By 2007, every wolf on the island was a direct descendant of the Old Gray Guy. Extreme inbreeding was inevitable.

As a result of long-term inbreeding, every wolf skeleton examined since 1994 shows striking skeletal deformities involving the ribs and vertebrae. This issue is a striking contrast to the situation among the Channel Island foxes, which show no such deformities. The difference probably lies in the details of the inbred wolves’ genomes. In any case, survival of pups is very low. The wolf population dropped from a high of 50 in 1980 to two individuals in 2016. Details of those two individuals just about ensure that the population will soon be extinct. The male and female share the same mother, and the male is also the female’s father. They produced a pup that was visibly deformed when seen in an aerial photograph taken in 2015. The pup is now believed to be dead.

These events may spell the end of the Isle Royale study, which after 59 years has provided ground-breaking results and revolutionized our understanding of wolves, moose, and predator-prey relations. In 2012, longtime leaders of the study, Rolf Peterson and John Vucetich of Michigan Technological University, called on the National Park Service to import some mainland wolves to revitalize the population. Skeptics, including wolf expert L. David Mech, whose early research was carried out on Isle Royale, advised “watchful waiting” instead.

In contrast to the Channel Islands case, waiting prevailed in Isle Royale, and no rescue or conservation efforts were undertaken. It is now clear that the National Park Service waited too long. A genetic rescue cannot work now, with only two aging and inbred wolves left. The only hope for preserving the forest, the moose, and the ecosystem is to start over.

“At this point I advocate a restart for the wolf population, with animals from the mainland released on Isle Royale,” Peterson wrote in an email. Climate change is making it impossible for new wolves to migrate to Isle Royale on their own; ice bridges are even rarer than in the past. Doing nothing will encourage moose overpopulation that could irreparably damage the island forest and ecosystem.

Data from R. O. Peterson and J. A. Vucetich, 2016.

Distinctive or Doomed?

Should we intervene when human-caused problems heighten the chances of the extinction of a species or ecosystem? No one-size-fits-all policy is likely to work in all situations.

Genetic diversity is apparently not as vital as we once thought, based on the Channel Island foxes, nor can it be ignored, as the dwindling Isle Royale wolf population shows. Distinctive populations need to be monitored carefully and thoughtfully to improve our understanding of how ecosystems work. We also need to learn more about how widely the rise or fall in the population size of one species can affect other animals, plants, and sometimes water retention in the ecosystem.

Although there is much to be said for a “hands-off” approach, there is no denying that humans have already greatly modified the ecosystems of our world and will continue to do so. Conservation activities need to be taken early, when deleterious effects are observed and while there are still enough individuals in the various species to make ecosystem recovery possible.

Special, distinctive ecosystems and the species in them are of immense value. We should not sit idly by and watch them disappear.

Bibliography

- Coonan, T. 2014. Sixteenth Annual Meeting, Island Fox Working Group. Summary Report. Ventura, CA: Accessed September 14, 2016. http://www.mednscience.org/download_product/2085/0

- Funk, W. C., et al. 2016. Adaptive divergence despite strong genetic drift: Genomic analysis of the evolutionary mechanisms causing genetic differentiation in the island fox (Urocyon littoralis). Molecular Ecology 25:2176–2194.

- Hofman, C. A., et al. 2015. Mitochondrial genomes suggest rapid evolution of dwarf California Channel Islands foxes (Urocyon littoralis). PLoS ONE 10:e0118240.

-

- Mech, L. D. 2013. The case for watchful waiting with Isle Royale’s wolf population. The George Wright Forum 30(3):326–332.

- Peterson, R. O., and J. A. Vucetich. 2016. Ecological studies of wolves on Isle Royale annual report 2015–16. Accessed September 14, 2016. http://www.isleroyalewolf.org/sites/default/files/annual-report-pdf/annual%20rep%202016%20webversion.pdf

- Robinson, J. A., et al. 2016. Genomic flatlining in the endangered island fox. Current Biology 26:1183–1189.

- Vucetich, J. A., M. P. Nelson, and R. O. Peterson. 2012. Should Isle Royale wolves be reintroduced? A case study on wilderness management in a changing world. The George Wright Forum 29(1):126–147.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.