This Article From Issue

March-April 2018

Volume 106, Number 2

Page 73

Nanoparticles are now commonplace in consumer products, and their disposal is leading to more nanoparticles entering the environment. Although questions about the toxicity of such nanoparticles have been in the news lately, Alexander Orlov, a materials scientist at the State University of New York at Stony Brook and a Sigma Xi Distinguished Lecturer, believes there are ways of designing nanoscale materials that avoid any such potential problems, even those that may not yet exist. Orlov focuses on the use of nanoscale materials in environmental cleanup and energy production. He spoke about his research with American Scientist editor-in-chief Fenella Saunders. A video of the full discussion is available below.

Alexander Orlov

What defines the nanoscale?

There’s a little bit of a debate on that, but conventionally it’s the size below 100 nanometers. When you go below that size regime, you start getting very unusual and very exciting properties.

What are some examples of recognizable things at that scale?

Some large-scale molecules can reach a nanometer in size; viruses can be below a micron and can approach that 100-nanometer size. You can see nanoparticles indirectly if you go to a medieval church and look at the stained glass windows. Even though you don’t see nanoparticles, a combination of very small particles of gold and silver are creating the vivid color.

Why does the nanoscale change the properties of some very familiar materials, so that a different color is created from gold and silver?

When you decrease the particle size of gold to around 10 nanometers, you start seeing colors that are not typical for gold. If you have 5 to 10 atoms, they are very reactive. When you have 100 atoms, they are not. It’s almost like a human analogy to unhappy nanoparticles. If you’re a lonely, solo atom and you don’t have neighbors, you’re not happy and you try to form a bond with a similar atom or some molecule flying nearby. When you have 10 or 15 atoms, you’re not reaching outside the ones surrounding you, and you become less unhappy. You’re not trying to reach those molecules nearby and convert them to something else. And if you’re surrounded by a lot of atoms, in this case you’re probably very happy and reactivity goes down.

How does your research into energy production work?

Gold nanoparticles can decompose various molecules. One way we utilize this property is to add these very small particles to water, shine a light, and they can produce fuel out of the water, because they can split it to hydrogen and oxygen.

How do you use nanoparticles to decompose pollutants?

We collaborate with a company and use an inexpensive material, titanium dioxide. It’s the same material in your toothpaste, but there’s a way to process it so it is activated by sunlight. When it absorbs light, it becomes active in decomposing pollutants. For example, if we could coat a large building or stadium with these nanoparticles, those buildings could clean up the air, removing the most dangerous pollutants.

Sunlight is your driving force—it’s the engine. It excites electrons in the particles to the next energy level, which leaves behind a hole. The molecule tries to oxidize various molecules from anywhere it can, to get an electron into that space. And those target molecules are absorbed from the surface of the particle. In the meantime, the excited electron also is trying to react with other types of molecules on the surface.

How do you create some of these nanoparticles?

There probably are at least 10 different methods of making nanoparticles. It can be something you do easily by mixing chemicals in a beaker, but there are more exotic methods. In one of the recent ones we used, we cooled helium almost to absolute zero, and by pushing it through a nozzle, we created helium nanodroplets. And when those droplets were flying from the nozzle, we infused them with nanoparticles, so in the end we had very pure and uniform particles with really incredible properties.

Do you take any inspiration from nature’s nanoscale methodology?

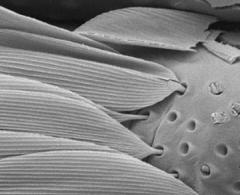

Rather than copying nature in a blind way, a better way of being in control to solve a problem is to try to understand why nature has done it that way and what challenges it was trying to solve, and then to modify the approach. When we try to use nature as an inspiration to solve engineering problems or to create nanoparticles, we have to be very careful, because nature had millions of years to optimize those solutions and it’s optimizing for multiple challenges. For example, we’re looking at the structures in butterfly wings, and they use nanotechnology to solve two problems: color and water repellence. Nature optimized the structures for these two challenges. But if you try to use those structures for just one of the challenges, it might not be the most optimal solution.

How should concerns about the safety of nanoparticles be addressed?

When a material in bulk form is inert, but becomes reactive at the nanoscale, in this case there’s a possibility of toxicity. One solution is to ask toxicologists to test it before you start producing it. But a lot of toxicological testing can be contradictory, so it would take some time to understand the full meaning of those tests, and even now we are discussing contradictory studies about relatively simple nanoparticles. For seven years I was an advisor to the secretary of state in the United Kingdom on safety of nanotechnology, and working with toxicologists you realize the limitation of their studies and knowledge. But we need to overcome barriers and push together nanotechnology scientists and toxicologists to have testing early enough, especially when we start putting nanoparticles in consumer products. That’s something we are working on; we’re looking at the safety of carbon nanotubes incorporated in various polymers.

How can you change the design of nanoparticles right from the beginning to make them potentially less harmful?

If you’re never exposed to a substance, and it never gets into your body, it doesn’t matter whether it is toxic or not. If you have nanoparticles and they’re incorporated in concrete, or are always encapsulated in something that will never degrade and you’ll never release them into the environment, you don’t need to worry too much about them. This is green chemistry design, so you think about what would happen after the end of life of this product—where it’s going to end up, whether there’s a possibility that particles are going to get released, and whether you need to collect them before you dispose of them in a trash bin. You may not have all the information about toxicity, so you design the consumer product for the worst-case scenario so that the particles will never get released into the environment.

This area of research has seen steady funding for a number of years, but could that change in the current political climate because of the connections to energy and the environment?

The National Nanotechnology Initiative started under President Clinton. When the Bush administration came in, continuation of funding was probably the least controversial idea because the economic benefits are significant. During the Obama administration, the budget remained almost the same. Hopefully it will continue under the new administration. You can see the application of nanotechnology in everything from your phone to medicine. You can justify the economic benefits of nanotechnology relatively easily, so based on the record of going from Republican administrations into Democratic ones and vice versa, it hasn’t been a controversial initiative.

What motivates you to continue your research focus in nanotechnology?

One of the reasons I try to combine energy and environment into my research is my childhood experience in Ukraine. I was there during the Chernobyl explosion, and I remember doing shopping with a Geiger counter. At that particular time they didn’t evacuate kids, because they didn’t want to disclose the nature of that explosion, and the products coming to the capital of Ukraine were contaminated to the level that sometimes the Geiger counter was going off the scale.

There is also overlap between energy and environment in developing countries. I shared this experience when I was giving a lecture at the World Bank about sustainability and nanotechnology in Vietnam, because a public official asked why they should care about the environment when they need to feed people. It made me realize that culturally there’s diversity in understanding the value of human life and a clean environment. Sometimes sharing a painful experience like I had helps others in understanding what would happen at the extreme; when you don’t care about the environment, you don’t care about human life.

The pollution-absorbing materials you helped develop were used in a sculptural installation at a facility of New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 2012. What role can art play in the public understanding of nanotechnology?

The idea was fascinating in a way that, when you have this wonderful property of cleaning up the air, it’s a bit difficult to demonstrate it publicly. If you say the air is cleaner, you might be able to sense it, but air pollution has relatively indirect effects. The New York City Department of Health says 3,000 people die there every year because of air pollution. But if air is contaminated, sometimes you can feel it, sometimes you cannot. That particular project showed that the buildings can be greener, they can actually serve as something that can clean up the environment rather that pollute it. I think educating the public about air quality and environmental issues in a creative way is very important.

Another project the company I work with did was in collaboration with the London Institute of Fashion. They coated jeans with that material, and the idea was that you walked around the city and purified the air. So it’s a sort of distributed purification type of approach.

In another project, my colleagues at Sheffield University in the United Kingdom had a billboard on which they wrote a poem about how it’s wonderful to have clean air. Meanwhile this billboard was covered with this air-purifying coating, and they’re claiming that it’s the first-ever air-purifying poem in the world. Those are some of the creative ways to demonstrate nanotechnology and improve public understanding of it.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.