Quantum Randomness

By Scott Aaronson

If there’s no predeterminism in quantum mechanics, can it output numbers that truly have no pattern?

If there’s no predeterminism in quantum mechanics, can it output numbers that truly have no pattern?

DOI: 10.1511/2014.109.266

How can you know whether a sequence of numbers is random? Suppose, for example, that you buy an alleged random-number generator for use in creating cryptographic keys, and suppose the generator spits out something like:

84, 67, 33, 68, 81, 29, 83, 90, 26, . . .

The numbers look pretty random, but can you be confident that there’s no hidden pattern—perhaps because of a backdoor secretly inserted by the manufacturer or some other privacy interloper?

Illustration by Tom Dunne.

So certifying randomness is both a philosophical problem and an urgently practical one. In the last issue’s Technologue column, I discussed an abstract, conceptual solution to the problem of how to certify randomness, based on a seminal idea from the 1960s called Kolmogorov complexity. To recap, the Kolmogorov complexity of a string of bits is defined as the length of the shortest computer program that produces the string as output. In several ways that one can make precise, a string of n bits can be called “random for all practical purposes” if its Kolmogorov complexity is close to n. In such a case, the string is “algorithmically incompressible”: The shortest computable description of it is the string itself.

Alas, although Kolmogorov complexity might lead to deep insights about the nature of randomness, there’s a huge problem with applying it to real life. Namely, as I proved in the last issue, there’s no algorithm to compute the Kolmogorov complexity of a given string! People sometimes try to get around this problem by approximating Kolmogorov complexity but it’s not always effective.

If we really want to be sure that a sequence is random, we’ll have to exploit some knowledge about how the numbers were generated: Did they come from die rolls? Radioactive decays? A computer program? Whichever physical process produced the numbers, what reasons do we have to believe the process was random?

At this point, the impatient reader might shout: If you want guaranteed randomness, why not just use quantum mechanics? After all, quantum mechanics famously says that you can’t predict with certainty whether, say, a radioactive atom will decay within a specified time period, even given complete knowledge of the laws of physics as well as the atom’s initial conditions. The best you can do is to calculate a probability.

But not so fast! There are two problems. Quantum-mechanical random number generators do exist and are sold commercially. But hardware calibration problems really can make the numbers predictable if they’re not fixed. Furthermore, even if you couldn’t predict the numbers better than chance, how could you be sure there wasn’t some subtle regularity that would let someone else predict them?

The second problem is philosophical, and goes back to the beginning of quantum mechanics. It’s well known that Einstein, in his later years, rejected quantum indeterminism, holding that “God does not play dice.” It’s not that Einstein thought quantum mechanics was wrong, he merely thought it was incomplete, needing to be supplemented by “hidden variables” to restore Newtonian determinism. Today, it’s often said that Einstein lost this battle, that quantum indeterminism triumphed. But wait! Logically, how could Einstein’s belief in a hidden determinism ever be disproven? Can you ever rule out the existence of a pattern, just because you’d failed to find one?

The answer to this question takes us to the heart of quantum mechanics, to the part that popular explanations usually mangle. Quantum mechanics wasn’t the first theory to introduce randomness and probabilities into physics. Ironically, the real novelty of quantum mechanics was that it replaced probabilities—which are defined as nonnegative real numbers—by less intuitive quantities called amplitudes, which can be positive, negative, or even complex. To find the probability of some event happening (say, an atom decaying, or a photon hitting a screen), quantum mechanics says that you need to add the amplitudes for all the possible ways that it could happen, and then take the squared absolute value of the result. If an event has positive and negative amplitudes, they can cancel each other out, so the event never happens at all.

The key point is that the behavior of amplitudes seems to force probabilities to play a different role in quantum mechanics than they do in other physical theories. As long as a theory only involves probabilities, we can imagine that the probabilities merely reflect our ignorance, and that a “God’s-eye view” of the precise coordinates of every subatomic particle would restore determinism. But quantum mechanics’ amplitudes only turn into probabilities on being measured—and the specific way the transformation happens depends on which measurement an observer chooses to perform. That is, nature “cooks probabilities to order” for us in response to the measurement choice. That being so, how can we regard the probabilities as reflecting ignorance of a preexisting truth?

Well, maybe it’s possible, and maybe not. The answer’s not obvious, and wasn’t until the 1960s—after Einstein had passed away—that the situation was finally clarified, by physicist John Bell. What Bell showed is that, yes, it’s possible to say that the apparent randomness in quantum mechanics is due to some hidden determinism behind the scenes, such as “God’s unknowable encyclopedia” listing everything that will ever happen. That bare possibility has no experimental consequences and can never be ruled out. On the other hand, if you also want the hidden deterministic variables to be local—that is, to obey the inherent impossibility of faster-than-light communication—then there’s necessarily a conflict with the predictions of quantum mechanics for certain experiments. In the 1970s and 1980s, the requisite experiments were actually done—most convincingly by physicist Alain Aspect—and they vindicated quantum mechanics, while ruling out local hidden variable theories in the minds of most physicists.

To clarify, these experiments didn’t rule out the possibility of any determinism underneath quantum mechanics; that’s something that no experiment can do in principle. There’s even a theory, Bohmian mechanics (named after physicist David Bohm), that reproduces all the predictions of quantum mechanics, by imagining that besides the amplitudes, there are also actual particles that move around in a deterministic way, guided by the amplitudes. Bohmian mechanics is extremely strange, because it involves instantaneous communication between faraway particles, though not of a kind that could actually be used to send messages faster than light. In essence, what Bell’s theorem shows is that if you want a deterministic theory underpinning quantum mechanics, then it has to be strange in exactly the same way Bohmian mechanics is strange: It has to be “nonlocal,” resorting to instantaneous communication to account for the results of certain measurements. In fact, understanding this aspect of Bohmian mechanics is what motivated Bell to prove his theorem in the first place.

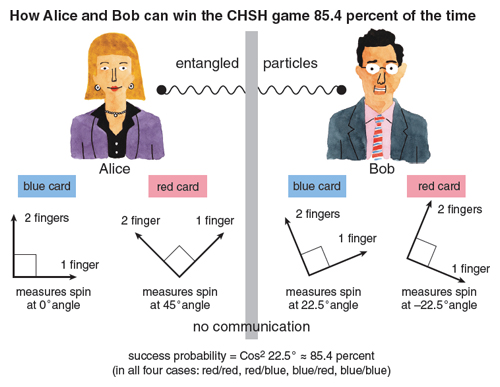

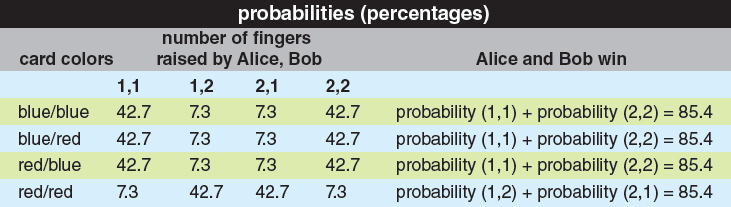

I’d like to explain Bell’s idea as a simple mathematical game (called the CHSH game, after its inventors, Clauser, Horne, Shimony, and Holt). This game involves two players, Alice and Bob, who are cooperating rather than competing. Alice and Bob can agree on a strategy in advance: There can be unlimited “classical correlation” between them. Once the game starts, however, no further communication is allowed. (We can imagine, if we like, that Alice stays on Earth while Bob travels to Mars.)

After they separate, Alice and Bob each open a sealed envelope, and find either a red or a blue card inside. The cards were chosen randomly, so that there are four equally likely possibilities: blue/blue, blue/red, red/blue, and red/red. After examining her card, Alice can raise either one or two fingers, and after examining his card, Bob can do likewise. Alice and Bob win the game if either both cards were red and they raised different numbers of fingers, or at least one card was blue and they raised the same number of fingers.

The question that interests us is, what is the best strategy for Alice and Bob—the one that lets them win this strange game with the maximum probability? As an exercise, I invite you to check that the best strategy is a rather boring one: Alice and Bob both just ignore their cards and raise one finger. Using this strategy, our heroes will win 75 percent of the time, whenever one or both cards are blue. The Bell inequality is simply the statement that no strategy does better than this.

On the other hand, suppose that before Alice and Bob separate, they put two electrons into a so-called Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen pair, a configuration where there’s some amplitude for both electrons to be spinning left, and an equal amplitude for both electrons to be spinning right. This pair is the most famous example of an entangled state: Roughly speaking, a combined quantum state of several particles that can’t be factored into states of the individual particles. (For our purposes, it doesn’t matter what it means for an electron to be “spinning left or right,” it’s just some property of the electron.) Then, when they separate, Alice takes one electron and Bob takes the other.

Illustration by Barbara Aulicino.

In this case, Bell showed that there’s a clever strategy where Alice and Bob use measurements of their respective electrons to correlate their responses—in such a way that no matter which cards they get, they win the game 85.4 percent of the time. Because 85.4 percent is more than 75 percent, there can be no way to describe the state of Alice’s electron separately from the state of Bob’s electron—if there were, then Alice and Bob couldn’t have won more than 75 percent of the time. To explain their success in the game, you need to accept that no matter how far apart Alice and Bob are, their electrons remain quantum mechanically entangled. (See the figure on the first page and table above.)

Before going further, it’s worth clarifying two crucial points. First, entanglement is often described in popular books as “spooky action at a distance”: If you measure an electron on Earth and find that it’s spinning left, then somehow, the counterpart electron in the Andromeda galaxy “knows” to be spinning left as well! However, a theorem in quantum mechanics—appropriately called the No-Communication Theorem—says that there’s no way for Alice to use this effect to send a message to Bob faster than light. Intuitively, this is because Alice doesn’t get to choose whether her electron will be spinning left or right when she measures it. As an analogy, by picking up a copy of American Scientist in New York, you can “instantaneously learn” the contents of a different copy of American Scientist in San Francisco, but it would be strange to call that faster-than-light communication! (Although this might come as a letdown to some science fiction fans, it’s really a relief: If you could use entanglement to communicate faster than light, then quantum mechanics would flat-out contradict Einstein’s special theory of relativity.)

However, the analogy with classical correlation raises an obvious question. If entangled particles are really no “spookier” than a pair of identical magazines, then what’s the big deal about entanglement anyway? Why can’t we suppose that, just before the two electrons separated, they said to each other “hey, if anyone asks, let’s both be spinning left”? This, indeed, is essentially the question Einstein posed—and the Bell inequality provides the answer. Namely, if the two electrons had simply “agreed in advance” on how to spin, then Alice and Bob could not have used them to boost their success in the CHSH game. That Alice and Bob could do this shows that entanglement must be more than just correlation between two random variables.

To summarize, the Bell inequality paints a picture of our universe as weirdly intermediate between local and nonlocal. Using entangled particles, Alice and Bob can do something that would have required faster-than-light communication, had you tried to simulate what was going on using classical physics. But once you accept quantum mechanics, you can describe what’s going on without any recourse to faster-than-light influences.

Bell’s theorem can also be understood in another way: as using the assumption of no faster-than-light communication to address the even more basic question of predictability and randomness. It’s probably easiest to explain this idea via an example.

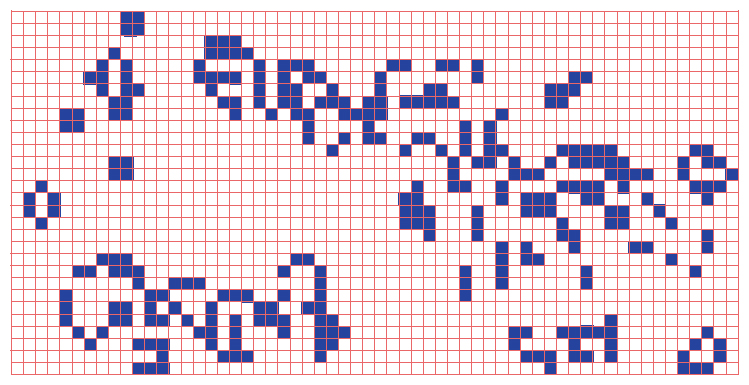

In 2002, Stephen Wolfram published his 1,200-page book A New Kind of Science, which set out to explain the entire universe in terms of computer programs called cellular automata. You can think of a cellular automaton as a giant array of 0s and 1s that get updated in time by a simple, local, deterministic rule. For example, “if you’re a 0, then change to 1 only if three of your eight neighbors are 1s; if you’re a 1, then stay 1 only if either two or three of your eight neighbors are 1s.” (This rule defines Conway’s Game of Life, one of the most popular cellular automata, invented by mathematician John Conway in 1970.)

Illustraion courtesy of the author.

Despite their almost childish simplicity, cellular automata can produce incredibly complex behavior (see the figure above), such as “particles” and other structures that travel across the array, collide, merge, and disintegrate, and sometimes even seem to act like living organisms. Witnessing this behavior, generations of programming hobbyists have speculated that our own universe might be a cellular automaton at its base, a speculation that Wolfram embraces with gusto.

Personally, I have no problem with the general idea of describing nature as a simple computation—in some sense, I’d say, that’s the entire program of science! When I read Wolfram’s book, however, I had difficulties with the specific kind of computation he asserted could do the job. In particular, Wolfram insisted that the known phenomena of physics could be reproduced using a classical cellular automaton: that is, one where the bits defining “the state of the universe” are all either definitely 0 or definitely 1, and where the apparent randomness of quantum mechanics arises solely from our own ignorance about the bits. Wolfram knew that such a model would imply that quantum mechanics was only approximate, so that (for example) quantum computers could never work. However, it seemed to me that Wolfram’s idea was ruled out on much simpler grounds, namely Bell’s theorem. That is, because a classical cellular automaton would allow only correlation, rather than quantum entanglement, it would lead us to predict wrongly that the CHSH game can be won at most 75 percent of the time.

Wolfram had a further complication up his sleeve, however. Noticing the difficulty with explaining entanglement, he added a conjecture that, when two particles become entangled, a “long-range thread” forms in the cellular automaton, connecting two locations that would otherwise be far apart. Crucially, these long-range threads would not be usable for sending messages faster than light, or for picking out a “preferred frame of reference”; Wolfram knew that he didn’t want to violate special relativity. Rather, in some way that Wolfram never explained, the threads would only be useful for reproducing certain predictions of quantum mechanics, such as the one that the CHSH game can be won 85.4 percent of the time.

It turned out that the idea was still unworkable. In a 2002 review of Wolfram’s book, I proved that the long-range thread idea can’t possibly do what Wolfram wanted. More precisely, I showed that if a long-range thread can be used to win the CHSH game more than 75 percent of the time, then that thread also picks out a preferred frame of reference, or (worse yet) creates closed timelike curves, where time loops back on itself, which would allow Alice and Bob to send messages to their own pasts. (Note that Bohmian mechanics doesn’t contradict this theorem, because it does pick a preferred frame of reference. But such a frame—that is, something that tells you whether Alice or Bob made their measurement “first”—is what Wolfram had been trying to avoid.)

At the time I wrote down this observation, I didn’t think much of it, because the argument was just a small variation on ones that Bell and the CHSH game creators had made decades earlier. In 2006, however, the observation attracted widespread attention, when John Conway (the same one from Conway’s Game of Life) and Simon Kochen presented a sharpened and more general version, under the memorable name “The Free Will Theorem.” Conway and Kochen phrased their conclusion as follows: “if indeed there exist any experimenters with a modicum of free will, then elementary particles must have their own share of this valuable commodity.” To put it differently: Assuming no preferred reference frames or closed timelike curves, if Alice and Bob have genuine “freedom” in deciding how to measure entangled particles, then the particles must also have “freedom” in deciding how to respond to the measurements.

Unfortunately, Conway and Kochen’s use of the term “free will” generated a lot of avoidable confusion. For the record, what they meant by “free will” has almost nothing to do with what philosophers mean by it, and certainly nothing to do with human agency. A better name for the Free Will Theorem might’ve been the “Freshly-Generated Randomness Theorem.” For if you want to understand what the theorem says, you might as well imagine that Alice and Bob are dice-throwing robots rather than humans, and that the “free will of the elementary particles” just means quantum indeterminacy. The theorem then says:

Suppose you agree that the observed behavior of two entangled particles is as quantum mechanics predicts (and as experiment confirms); that there’s no preferred frame of reference telling you whether Alice or Bob measures “first” (and no closed timelike curves); and finally, that Alice and Bob can both decide “freely” how to measure their respective particles after they’re separated (i.e., that their choices of measurements aren’t determined by the prior state of the universe). Then the outcomes of their measurements also can’t be determined by the prior state of the universe.

Although the assumption that Alice and Bob can “measure freely” might seem strong, all it amounts to in essence is that there’s no “cosmic conspiracy” that predetermined how they were going to measure. At least one distinguished physicist, the Nobel laureate Gerard ‘t Hooft, has actually advocated such a cosmic conspiracy as a way of escaping the implications of Bell’s theorem. To my mind, however, such a conspiracy is no better than believing in a God who planted fossils in the ground to confound paleontologists.

So now that we know something about Bell’s theorem, and the inherent randomness of quantum measurement outcomes, what are the implications for our original subject—how to generate numbers that are guaranteed to be random? You might think that the problem is now solved! After all, Bell’s theorem reassures us that quantum measurement outcomes really are unpredictable, just as quantum mechanics always claimed they were.

Well, not so fast. There’s still the problem that you might not believe that some particular quantum random-number generator is free of hardware problems that introduce subtle biases. Or you might even worry about more bizarre possibilities, such as that nature delivers true random numbers “when it needs to” (as in the specific case of the CHSH game) but reverts back to determinism for other quantum experiments.

For both reasons, a natural idea would be to use Alice and Bob’s outputs in the CHSH game themselves as a source of random numbers. After all, if we find Alice and Bob winning the CHSH game 85.4 percent of the time, despite being far away from each other, then we become authorized to make an extremely strong statement: “Either Alice and Bob’s outputs had genuine unpredictability to them, or else the causal structure of spacetime itself is nothing like what we thought it was.”

Crucially, nowhere in this statement do we need to assume the correct functioning of Alice and Bob’s hardware, or even the truth of quantum mechanics itself. Yes, both of those assumptions are relevant to explaining why Alice and Bob can win the CHSH game 85.4 percent of the time. However, once a skeptic sees that they are winning the game with the requisite probability, that fact (plus the causal structure of spacetime) is all the skeptic needs to know. There’s nothing further about physics that needs to be accepted on faith.

However, when we think more about this idea of using the CHSH game as a random number source, a new difficulty crops up. Namely, for Alice and Bob to play the CHSH game in the first place, they need inputs (the colors of their respective cards), and those inputs are already supposed to be random! So to get randomness out, we need to put randomness in, and it’s not clear that there’s ever any net benefit.

Maybe there’s a way to modify the game, so that we get out more randomness than we have to put in. If so, then even if we had to start with a small random “seed,” there could still be an immense gain as we use CHSH to grow our seed into a much larger number of random bits.

The question of whether this sort of “quantum-certified randomness expansion” is possible was firrst asked by Roger Colbeck, in his 2006 Ph.D. thesis. Along with Adrian Kent, Colbeck gave a protocol that used a CHSH-like game to increase the number of random bits available by a fixed percentage. For example, starting with 100 random bits, the scheme could produce 130 or so as output, whereas starting with 1,000, it could produce 1,300. Then, in a 2010 Nature paper, Stefano Pironio of the Free University of Belgium and his colleagues did better, showing how to use CHSH to expand an n -bit random starting seed into about n2 bits of random output. How far could this go? In 2012, Umesh Vazirani and Thomas Vidick showed for the first time how to achieve exponential randomness expansion, using only about n bits of random input to get 2n bits of random output.

The central idea in all of these protocols is simply to be stingy with the use of randomness. We ask Alice and Bob to play the CHSH game over and over again. However, in almost all of the plays, they simply both receive red cards—leading to a boring but also “cheap” (in terms of randomness) game. Only for a few randomly chosen plays does one of them receive a blue card. However, if, say Alice receives a red card, she has no idea whether this is one of the rare plays that “counts” and is one where Bob received a blue card, and vice versa. So, not knowing which plays they’re being “tested on,” Alice and Bob have no choice but to play the game correctly, and therefore generate random bits, for almost all of the plays. The cleverer you are at sticking in the “spot checks,” the more randomness expansion you can get.

For technical reasons, the protocol of Vazirani and Vidick couldn’t provide more than exponential expansion. But, frustratingly, there was no proof that even greater expansion wasn’t possible. Indeed, no one could rule out the amazing possibility of so-called infinite expansion: Starting from a fixed random seed (say of 1,000 bits), we could use Alice and Bob to get as many more random bits as we wanted, with no limit whatsoever. There was even an intuitive argument that suggested that infinite expansion should be possible; why not reinvest the randomness? That is, after running the Vazirani-Vidick protocol to turn n random bits into 2n bits, why not use the 2n bits to get 22n bits, and so on forever?

The difficulty comes down to a simple question: The output bits might be random, but to whom? They may look random to you, or to any third party (say, an eavesdropper), but not to Alice and Bob, because they generated the bits. So for example, suppose you were foolhardy enough to use those 2n bits as the seed for a second run of the Vazirani-Vidick protocol—greedily asking Alice and Bob, like the mythical Rumpelstiltskin, to spin them into 22n random bits. In that case, Alice and Bob could quickly figure out that your new “random challenges” were deterministically generated by the seed that they themselves had given you in the last round. So from that point forward, Alice and Bob could cheat, giving you bits that were almost entirely deterministic, and using randomness only to pass your occasional, predictable challenges. Maybe there’s a way to confuse Alice and Bob and force them to spin more randomness, but no one has figured it out yet.

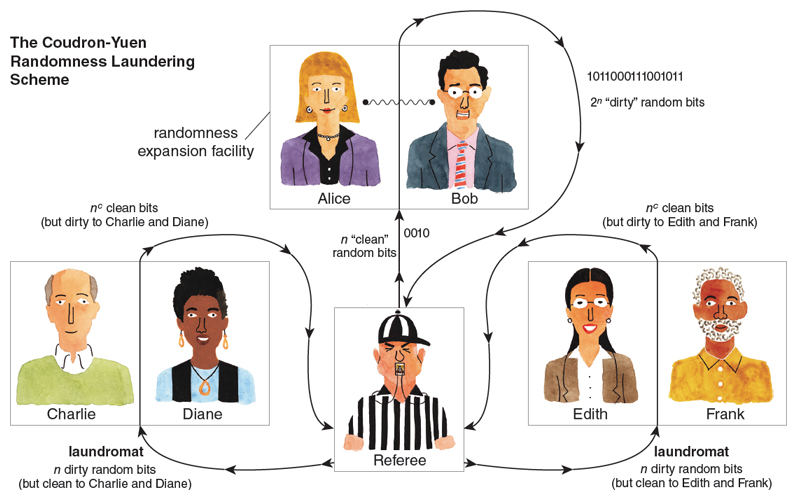

In the meantime, a simple fix is to bring in additional players. Suppose we have not only Alice and Bob, but also Charlie, Diane, Edith, and Frank. In that case, we can use Alice and Bob to spin n random input bits into 2n random output bits (random to everyone else, though not to Alice and Bob), then use Charlie and Diane to spin Alice and Bob’s 2n bits into 22n random bits, then use Edith and Frank to spin 22n bits into 222n bits, and so on. However, an obvious problem with this approach is that the more random bits we want, the more players we need.

If we want infinite randomness expansion with a fixed number of players, then we also need a “randomness-laundering scheme,” a way of taking random bits that are “dirty” (correlated with the players’ knowledge in some complicated way), and converting them into random bits that are “clean” (uncorrelated with at least some players’ knowledge). Crucially, such a randomness-laundering scheme would need to work even though Alice, Bob, and anyone we might use to execute the scheme might try to cheat, and keep the randomness “dirty” (that is, predictable to at least some of them).

Fortunately, it turns out that the CHSH game is a multipurpose tool: It also lets us launder randomness! That this ability is possible emerged from a seemingly unrelated 2012 breakthrough by Ben Reichardt, Falk Unger, and Umesh Vazirani. They proved a “rigidity theorem” for the CHSH game, showing that, if Alice and Bob play many instances of the game and win about 85.4 percent of them, then they must be measuring their entangled particles in a way that’s nearly “isomorphic” to the procedure shown in the figure on the first page. Even if we allow unlimited quantum entanglement, there’s no fundamentally different strategy that does as well at the CHSH game.

In 2013, MIT graduate students Matt Coudron and Henry Yuen put all the pieces together. First, by using Reichardt, Unger, and Vazirani’s rigidity theorem, they showed how to design a randomness laundering protocol which uses the two players Alice and Bob, takes n “dirty” random bits as input, and produces n c “clean” random bits as output, where c is some small positive constant (say, 1/10). The “dirty” bits could be correlated with anything except Alice and Bob themselves, whereas the “clean” bits are guaranteed to be uncorrelated with anything except Alice and Bob themselves. Notice that, just like a real laundry machine, the protocol actually shrinks the number of random bits every time it runs—the exact opposite of what we wanted! However, this polynomial shrinkage will be dwarfed by the exponential expansion provided by the Vazirani-Vidick protocol, so ultimately it won’t matter.

Illustration by Tom Dunne.

Coudron and Yuen’s final protocol (illustrated above) involves six players who perform alternating rounds of expanding and laundering. First Alice and Bob expand the original n -bit random seed into 2n dirty random bits. Next Charlie and Diane launder the 2n dirty bits to get 2cn clean bits. Then, having been laundered, these 2cn clean bits are ready for Alice and Bob to expand again, into 22cn dirty bits. Then Edith and Frank launder these 22cn dirty bits into 2c2cn clean bits, which Alice and Bob expand, and so on forever. We need two laundromats, working in alternate shifts, to clean the bits for the other players, so no one sees the same “dirty” bits twice.

Earlier this year, a simpler approach to infinite randomness expansion emerged from work by Carl Miller, Yaoyun Shi, Kai-Min Chung, and Xiaodi Wu. The new approach bypasses the need for Reichardt, Unger, and Vazirani’s rigidity theorem, and requires only four players rather than Coudron and Yuen’s six. It’s still not known whether infinite randomness expansion is possible using just two or three players. Also unknown, at present, is the exact number of random seed bits needed to jump-start this unending process: Do 1,000 seed bits suffice? 100? (In general, the answer will depend somewhat on just how statistically certain we want to be that the output bits are random.)

How can we know for sure if something is random? In this two-part series, I’ve tried to cover a century’s worth of thought about that question. We’ve seen statistical randomness tests, Kolmogorov complexity, Bell’s theorem, the CHSH game, the “Free Will Theorem,” and finally, recent protocols for generating what’s been called “Einstein-certified randomness.” Starting with a small random seed, these protocols use quantum entanglement to generate as many additional bits as you want that are guaranteed to be random—unless nature resorted to faster-than-light communication to bias the bits.

Pironio’s group has already done a small, proof-of-concept demonstration of their randomness expansion protocol, using it to generate about 40 “guaranteed random bits.” Making this technology useful will require, above all, improving the bit rate (that is, the number of random bits generated per second). But the difficulties seem surmountable, and researchers at the National Institute of Standards and Technology are currently working on them. So it’s likely that before too long, we will be able to have copious bits whose randomness is guaranteed by the causal structure of spacetime itself, should we want that. And as mentioned before, for cryptographic purposes it can matter a lot whether your randomness is really random.

Although there is a need for randomness, we normally don’t need huge amounts of it. Even for cryptographic applications, our computers rely heavily on pseudorandom number generators: Deterministic functions that start with a small random seed and stretch it out into a long string that “looks random for all practical purposes.” To clarify, the output is certainly not completely random, because the number of possible seeds is so much tinier than the number of possible long strings. However, according to current understanding in theoretical computer science, even if the seed was only a few thousand bits long, and the output was thousands of terabytes, telling the output apart from a truly random string could require astronomical amounts of computation. Indeed, even if the entire observable universe were converted into supercomputers working on telling the output from random, those supercomputers would probably have degenerated into black holes and radiation before they’d made a dent in the problem. Assuming that’s true, it would seem fair to say that the pseudorandom string is “random- looking enough,” and that the only true randomness we needed was that in the initial seed. When it comes to randomness, then, a little can go a long way—but you do need a little to get things started.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.