This Article From Issue

September-October 2014

Volume 102, Number 5

Page 391

DOI: 10.1511/2014.110.391

WHAT IF? Serious Scientific Answers to Absurd Hypothetical Questions. Randall Munroe. 320 pp. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2014. $24.00.

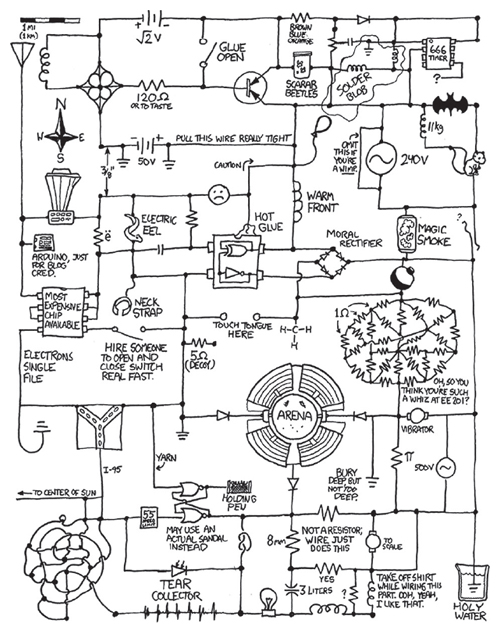

Question: What if you took a celebrated Internet cartoonist and set him loose on a bunch of wildly hypothetical science questions? Answer: You would get an incredibly fun book with quirky, hand-drawn pictures.

The cartoonist in question is Randall Munroe, and his much-anticipated first book, What If?, debuts in early September. In it, he presents a collection of essays that address queries submitted by readers of his acclaimed Web comic xkcd. For the past two years Munroe has been writing and illustrating weekly blog posts along these lines. The book selects from these posts and expands on them, taking the opportunity to discuss a breadth of scientific, technical, and mathematical topics in whimsical, illuminating ways.

Is it possible, one reader asks, to build a jetpack using downward-firing machine guns strapped to your back? Surprisingly, the answer is yes. From another reader: How many kilowatts of power can Yoda generate using the Force? Turns out, it’s about 19.2 kilowatts, depending on your estimates for the weight of an X-wing starfighter and the gravitational constant on Dagobah. At least it’s green energy. (Green, like Yoda. Get it?) How much suction power does a lifetime of kissing generate? We’re on our own with this one: There are some questions even Munroe won’t answer. He relegates them to purgatory-like interchapters called “Weird and Worrying Questions from the What If? Inbox,” which present queries he has deemed too strange for any response other than a wry drawing.

The many questions that receive full replies are the kind you might imagine inquisitive youth (or drunk physics majors) asking themselves in moments of boredom. Munroe raises the ante with answers that are both playful and erudite, all of them illustrated with good humor in his signature stick-figure style.

Most of Munroe’s insights don’t lead to a happy ending. What would happen if the Sun suddenly went out? We’d all die, of course. What if you threw a baseball at nearly the speed of light? There would be a giant explosion. What if you flew a Cessna over Venus? It would erupt in flames immediately. But the direct answer is only the beginning. Munroe typically addresses the reader’s question in the first paragraph; from there his response often takes a 90-degree turn to explore a surprising implication or an interesting deeper question hidden within each seemingly simple opening scenario. For example, in answering what would happen if everyone in the world got together and jumped at the same time (little beyond brief pressure to the Earth’s crust and a loud noise), Munroe goes on to explore the post-jump logistics of 7 billion people dispersing from one place (this scenario doesn’t end well either).

From xkcd.

What If? has a lot of material, and a lot of audience, to draw on. xkcd launched in 2005 and according to Alexa, a company that measures Internet traffic, it is currently the most popular comic on the Web. Estimates put its Web traffic at well over a billion page views per year. Munroe covers a wide range of topics in xkcd; regular readers expect to see everything from programmers engaged in technical conversation to sprawling infographics to experimental comic art experiences. I suspect Munroe started the “What If?” project as an outlet for material that fell outside even the wide perimeter of xkcd—topics he couldn’t quite turn into comics but wanted to investigate in depth, then share his findings.

And share he does. Each answer allows readers to accompany Munroe on a “deep dive” of what Michael Stevens of the YouTube channel VSauce calls “hyper-curiosity”: an experience similar to what happens when you visit a site such as Wikipedia to answer a question and you follow link after link, exploring a topic layer by layer, until you end up in a thoroughly unexpected place. Munroe serves as an inspired guide for just this sort of quest. Although he may wander, it’s with purpose, and in the end each response generally finds its way to a thought-provoking conclusion brought home with a comical punchline. For instance, what if a glass of water was, all of a sudden, literally half empty? After a six-page, microsecond-by-microsecond play-by-play that details how the glass would implode, spraying glass shards everywhere, Munroe concludes: “If the optimist says the glass is half full, and the pessimist says the glass is half empty, the physicist ducks.”

Munroe has hit on a wonderful form of science and engineering communication that can do so much—extolling the value of analytical thinking, examining data, and doing back-of-the-envelope calculations (things that, to my annoyance, television programs such as Mythbusters don’t seem to do)—while entertaining readers at the same time.

The book opens with a disclaimer: “The author of this book . . . likes it when things catch fire and explode, which means he does not have your best interests in mind.” To dispel any doubt, it states outright, “Do not try any of this at home.” So in real life, don’t stand in your front yard and try to shoot enough arrows to blot out the Sun. Don’t even think about loading a firearm with a bullet as dense as a neutron star and shooting it at the Earth. Instead, block off a Saturday afternoon and try wrapping your mind around this cleverly entertaining book.

Jorge Cham is the creator of the comic strip Piled Higher and Deeper. He has a PhD in robotics from Stanford University.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.