Where the Xingu Bends and Will Soon Break

By Mark Sabaj Perez

A hotly contested megadam threatens an incubator for evolutionary diversity in Brazil.

A hotly contested megadam threatens an incubator for evolutionary diversity in Brazil.

DOI: 10.1511/2015.117.395

With its globally unique geomorphology, hydrology, and aquatic biota, Brazil’s Xingu River offers a seemingly foolproof argument for its preservation. Yet the will to harness the Xingu for hydroelectricity has prevailed

over decades of heroic efforts to sustain its natural course.

Verena Glass/Xingu Vivo

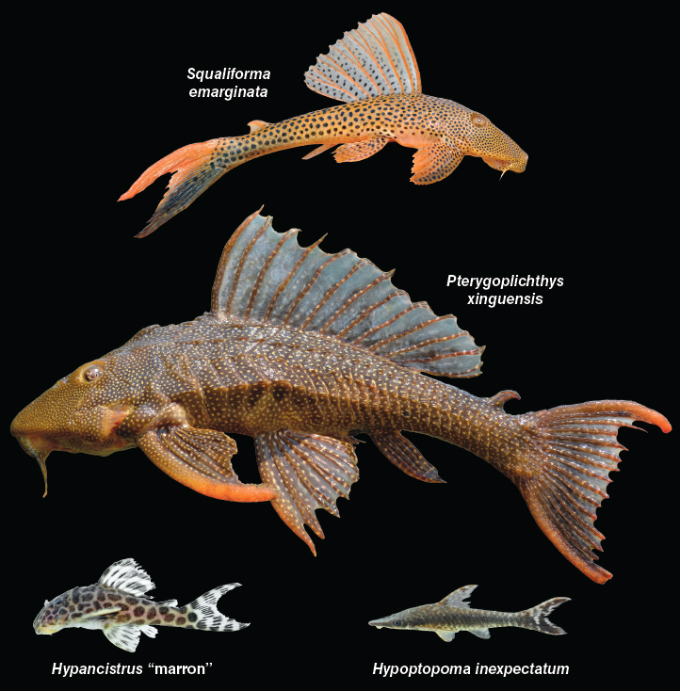

After four years of nearly round-the-clock construction, the Belo Monte megadam is set to become operational in the fall of 2015. At peak capacity, Belo Monte is expected to generate 11,233 megawatts, exceeded only by the Three Gorges Dam (22,500 megawatts) in China and the binational Itaipu Dam (14,000 megawatts) on the Paraná River between Brazil and Paraguay.

Belo Monte will directly affect at least 170 river kilometers of the Xingu channel by flooding nearly half that stretch and dewatering the rest. The response of rapids-loving fishes to the inundated portion will be as clear as the Xingu itself—they will decline in number if not disappear. Less clear is the fate of fishes inhabiting the Xingu below the reservoir and above Belo Monte, where the diverted water rejoins the main channel. That will depend largely on how much water is allowed to spill freely below the reservoir.

Tracking the environmental impacts of Belo Monte will require comprehensive data on local biodiversity and ecology prior to the dam’s completion. In the ongoing iXingu Project, American scientists such as myself have joined Brazilian efforts to establish that critical baseline.

“God only makes a place like Belo Monte once in a while. This place was made for a dam.” This remark by a barrageiro (dam builder), quoted by ecologist Philip Fearnside, echoes a distinct subculture in Brazilian society with grand ambitions for colossal dam projects, ostensibly to supply clean and renewable energy. At the close of 1984, the barrageiros could boast two important megadams: Itaipu, listed among the seven greatest civil engineering feats of the 20th century, and Tucuruí on the Tocantins River, the world’s fifth largest dam until Belo Monte is operational. In 1987, an epic national plan for electricity betrayed the barrageiros’ bravado. Produced by the Brazilian utility company Eletrobrás, the so-called “2010 Plan” listed 297 new dams to be constructed throughout Brazil in the coming decades. Included were five dams on the Xingu among a total of 79 dams sited throughout the Amazon Basin. Those dams would flood an estimated 10 million hectares or 3 percent of the originally forested Amazon Basin.

The barrageiro’s plans for the Xingu immediately ignited intense controversy, given the scope and magnitude of potential biological and cultural impacts. And so it began, the struggle over Belo Monte. Alongside the barrageiros, politicians publicly promoted Belo Monte as essential to energy security and economic progress. Aligned against Belo Monte were a broad coalition of indigenous tribes, grassroots organizations, academics, nongovernmental organizations, and government agencies responsible for protecting natural resources and the rights of dam-affected peoples. Early protests culminated in the First Meeting of Indigenous Peoples in Altamira in 1989 during which Tuíra, a member of the Kayapó tribe, laid her machete against the face of a chief engineer, becoming a global icon for hostility toward the Xingu dams.

The movement against the dams received a counterwarning in 2001 when the federal government began rationing electricity in response to a blackout crisis due in part to water shortages for hydroelectricity. That crisis revived plans for Belo Monte as a strategic interest for hydropower expansion. Since then, despite sustained and vocal opposition, Belo Monte has progressed through licensing to construction.

Amazon Watch/Spectral Q (top); Verena Glass/Xingu Vivo (bottom)

Over the course of one pilot and three full expeditions, the iXingu Project has gathered a wealth of specimens and empirical data that, when combined with Brazilian-led studies, afford a valuable snapshot of the fauna and ecology of the middle and lower Xingu. Such knowledge is essential for assessing the eventual impacts of Belo Monte and will inform future efforts to conserve what remains of the Xingu.

My first Xingu encounter was in 2007 on an expedition to its tributary, the Curuá, led by fellow ichthyologist José Luís Birindelli, then a doctoral student at the Universidade de São Paulo. On that trip I saw firsthand the effects of dam building on rapids.

Lalo de Almeida/Folhapress

The day we arrived at the Curuá, the barrageiros had just rerouted the entire river to dry down its streambed for construction of the impoundment dam. Trapped in pools of stagnant, muddy water were the tens of thousands of rapids-loving fishes that had occupied the river above a small waterfall. Such habitats are notoriously difficult to sample, their denizens kept secret by strong currents. That guilty glimpse taught me how productive such habitats can be and how little we know about tropical rapids.

After construction of Belo Monte began in 2011, I initiated a collaborative proposal to the U.S. National Science Foundation to inventory the aquatic diversity of lower Xingu rapids. Funded in 2013, the iXingu Project assembled an experienced team of aquatic biologists and their students from institutions in the United States and Brazil.

Barbara Aulicino

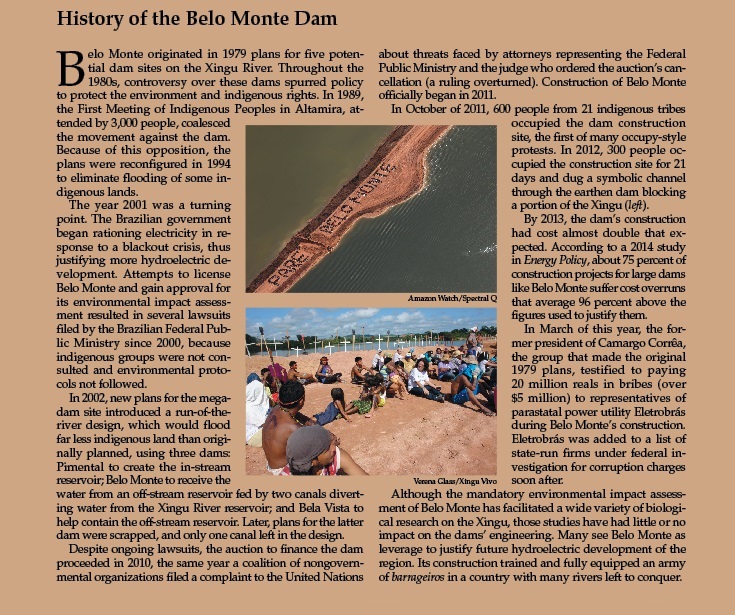

Our study focused on an extraordinary stretch of the Xingu known as Volta Grande, Portuguese for “Great Bend.” Over the course of 130 river kilometers, the third largest tributary to the Amazon falls 90 meters and changes course by about 90 degrees in each of three major bends. Volta Grande’s serpentine path marks the Xingu’s departure from the northern rim of the Brazilian Shield (above ). The first bend is at the riverfront city of Altamira, where a basalt sill halts the Xingu’s northerly course and sends it in a southeasterly direction. Just below Altamira, the Xingu is briefly a singular channel two kilometers wide. As it enters Volta Grande, the Xingu soon unravels into large and small braids loosely woven through countless lens-shaped islands and shoals. At the southern end of Volta Grande, the Xingu’s course is again disrupted, this time by the northwestern limits of the Três Palmeiras greenstone belt. Here, at the Xingu’s second major bend, the entire river is redirected northeasterly into the downstream half of Volta Grande.

Mark Sabaj Pérez

The lower leg of Volta Grande differs conspicuously from its upstream counterpart. Again, the river’s planform is extremely woven, but the braids are more intricate and often form linear channels where the water follows fractures in the basement rock. Some braids flow perpendicular to the overall course of the river, and many are redirected through acutely triangular turns. The result is a complicated labyrinth of watery channels, powerful rapids, and low waterfalls formed and bounded by granitic outcrops. The most spectacular cascades are cachoeira do Jericoá at the midpoint of Volta Grande’s lower leg, where much of the Xingu’s water tightly zigzags through a narrow Z-shaped channel in the broken bedrock (above). At the downstream limit of Volta Grande, three major braids coalesce into a channel that is about a half kilometer wide at its narrowest point and an astonishing 80 meters deep. Here, the Xingu completes its departure from the Brazilian Shield and gradually widens into an estuary-like ria as it flows through Paleozoic to Cretaceous sedimentary rocks to its confluence with the Amazon. Swift, rocky habitats persist in the so-called Xingu Ria, but as patchy remnants, many of them deeply submerged.

Belo Monte employs a run-of-the-river design with two major dams. The first, called Pimental, severs the upstream leg of Volta Grande. It will flood 382 square kilometers over an 80–river kilometer stretch of the Xingu, reducing its complexity of braids and rapids to an in-stream reservoir that will finish midway between Altamira and the mouth of its tributary, the Iriri. Just above Pimental, a large, artificial canal will divert the impounded water into an off-stream reservoir, flooding 134 square kilometers of land previously drained by four creeks. Water from the second reservoir will power the 20 turbines of the Belo Monte dam before rejoining the Xingu downstream of Volta Grande. A system of dykes will help keep the off-stream reservoir from escaping back into the downstream leg of Volta Grande. In effect, the entire dam complex will short-circuit the natural supply of water to over two-thirds of Volta Grande and attenuate the extreme seasonality of its hydrological cycle.

Google Earth

Rapids occur in many large rivers, but rarely if ever achieve the scale and complexity of Volta Grande. The hydrology of the Xingu further distinguishes it. With a catchment area of 446,573 square kilometers, nearly the size of France, the Xingu is the largest clearwater tributary to the Amazon, and second only to the rio Tocantins among all South American clearwaters. During the low-water season (August to November), visibility may exceed 2.5 meters, compared to 0.3 to 0.5 meters in the silt-laden Amazon.

Xingu waters run clear because their source is confined to the Brazilian Shield. Weathering over hundreds of millions of years has washed away soft sediments to expose the crystalline basement rock. The Xingu does carry a fair amount of coarse sand, supplied in part by the erosion of sandstones and shales in the Parecis sedimentary basin drained by the Xingu’s headwaters. The sand accumulates as beaches and shoals among the rocky outcrops. Brazilian geologist André Sawakuchi describes the Xingu as a prodigious polishing machine wherein rocks are worn smooth by sand suspended in the powerful rapids.

All images courtesy of the author except Pseudacanthicus "Xingu," by Leandro Sousa.

The Pimental Dam will transform much of the upstream leg of Volta Grande from a free-flowing lotic system to a still, depositional system. Sawakuchi notes that the river bottom in the reservoir will shift from bedrock to sand, silt, and mud, resulting in an environment similar to the Xingu Ria downstream. Below Pimental, the reduced supply of water will add blind alleys to Volta Grande’s maze of channels and diminish habitats and migratory routes suitable for rapids-loving fishes.

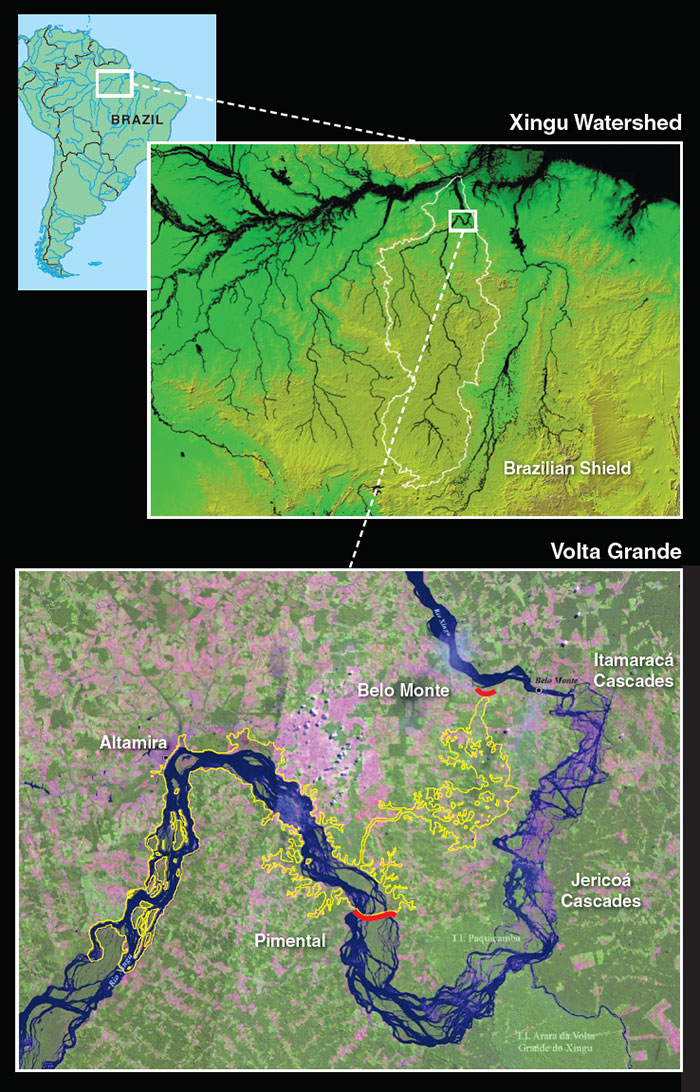

Like the Xingu, tributaries that drain the Brazilian Shield into Volta Grande are clearwaters. They resemble the Xingu channel with respect to temperature, pH, and clarity, but may differ in other qualities. For example, smaller tributaries tend to have lower concentrations of dissolved oxygen. Large tributaries, like the Bacajá, can have relatively high conductivity (a measure of dissolved ions), up to 66.2 microsiemens during the dry season, compared to a contemporary average of 18.9 microsiemens in the Xingu mainstem.

Barbara Aulicino; image courtesy of Daniel Fitzgerald.

The water qualities of tributaries that drain sedimentary beds into the Xingu’s Ria are quite different still. They are mostly blackwaters, darkly stained like tea by tannins leached from decaying vegetation. One such tributary, the Acaraí, is relatively cool, acidic, weakly conductive, and oxygen poor during the low-water season. In contrast, the Xingu channel is warmer, scarcely basic, moderately conductive, and richly oxygenated (above). The end result is a mosaic of seasonably variable water chemistries that add to the overall intricacy of the Xingu ecosystem. The direct impacts of Belo Monte on Xingu tributaries are relatively small; the in-stream reservoir will flood the mouths of some, and the off-stream reservoir will obliterate a few small creeks. The greatest threats to the Xingu’s tributaries are increased erosion and pollution due to the region’s rapid growth in population and infrastructure.

The Xingu’s extreme hydrological cycle superimposes yet another layer of complexity. During the high-water season (February to May), river discharge may exceed 32,000 cubic meters of water per second at Altamira, compared to minimum flows reaching 450 to 500 cubic meters per second in September and October. Furthermore, high-water flow rates during an average dry year (about 10,000 cubic meters per second) are only one-third that of an average wet year, resulting in a highly variable flood pulse from season to season. In any given year, the volume of water that enters Volta Grande during the driest month is only about 4 to 7 percent of peak flow, accounting for a 5-meter drop in river level. The drastically reduced flow further fragments Xingu habitats by isolating floodplain channels, pools, and lakes from the mainstem.

Mark Sabaj Pérez

Temporarily cut off from the Xingu’s buffering capacity, the water characteristics of such habitats diverge widely. Stagnant pools become oxygen depleted and over 10 degrees Celsius warmer than the river. Larger lakes can become oxygen rich due to blooms of phytoplankton. The main channel itself is more dissected—a “river of rivers,” with some braids approximating the fluvial morphology of much smaller rivers, brooks, and creeks. Conversely, in the high-water season, the water chemistry of the entire system is more homogenized, as once isolated habitats become connected to the main stem. The Xingu expands to fill the mouths of its tributaries and becomes highly integrated as rocky rapids and smaller channels disappear beneath the floodwaters.

After Belo Monte is operational, the barrageiros will determine the Xingu’s hydrological cycle to maximize the efficiency of the hydroelectric production. The amount of water received by the lower leg of Volta Grande will mimic seasonal fluctuations, but at a level far below average for the Xingu and without the natural variation between high-water seasons. The severe and chronic attenuation of the Xingu’s flood pulse will permanently isolate peripheral aquatic habitats from the main stem, rendering them unsuitable for many species. Furthermore, the Xingu’s annual flood pulse is likely the most biologically productive feature of the river’s ecosystem. The ultimate response of Volta Grande’s inhabitants to the new environmental flow regime is part of a grand experiment that no aquatic biologist would risk. The results could be catastrophic.

Mark Sabaj Pérez

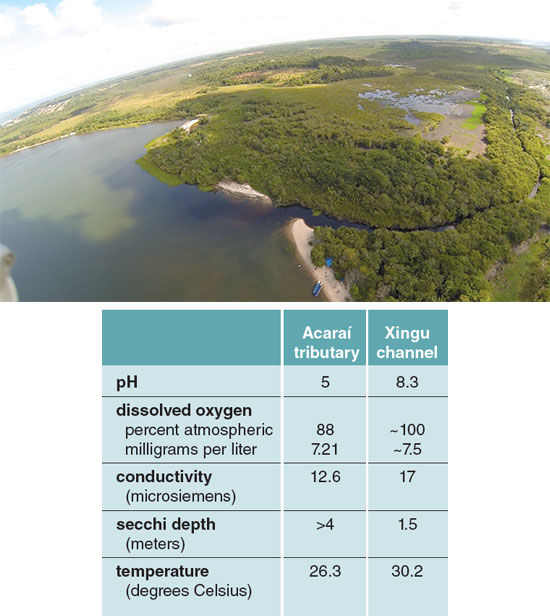

The Xingu’s complex geomorphology, collage of chemistries, and drastic hydrological cycle set the stage for brilliant performances of speciation and adaptation by an ensemble of over 450 fish species in 48 families. The stars of that stage are the plecos (above), catfishes of the family Loricariidae native to South and Central America. Their spectacular diversity and abundance in Volta Grande is unmatched. All plecos are ventrally flattened, with lips expanded and fused into a suction cup–like disk, adaptations for a prostrate lifestyle on silt, sand, stone, or wood. Leandro Sousa, an ichthyologist at the Universidade Federal do Pará in Altamira, has documented at least 45 species-level taxa representing 26 genera within the Xingu rapids. Based on his work with ornamental fishermen, Leandro hypothesizes that the life histories of plecos are finely tuned to Xingu’s habitat complexity, with different species or age groups specializing on particular niches segregated by depth, flow, and substrate.

Mark Sabaj Pérez

Most Xingu plecos are endemic to the basin, and two are exclusive to Volta Grande: Hypancistrus zebra and a taxonomically nameless congener. The former, commonly known as the zebra pleco for its black and white stripes, is an archetype of the tropical fish hobby. Formally described in 1991, the species first gained international attention after aquarists Minoru Matsuzaka and Grande Ogawa exported it to Japan in 1987. Today, a breeding pair of wild-caught zebras can fetch over $600 in the United Kingdom. Although profits go largely to intermediaries, many Altamira fishermen earn a modest living collecting zebra and other Xingu plecos for the tropical fish trade. Belo Monte will eliminate not only the zebra pleco’s natural habitat, but the most profitable fishing grounds for local ornamental fishermen. Ironically, zebra plecos now inhabit shop and home aquariums in such quantities that captive stocks may soon outnumber wild ones.

Mark Sabaj Pérez

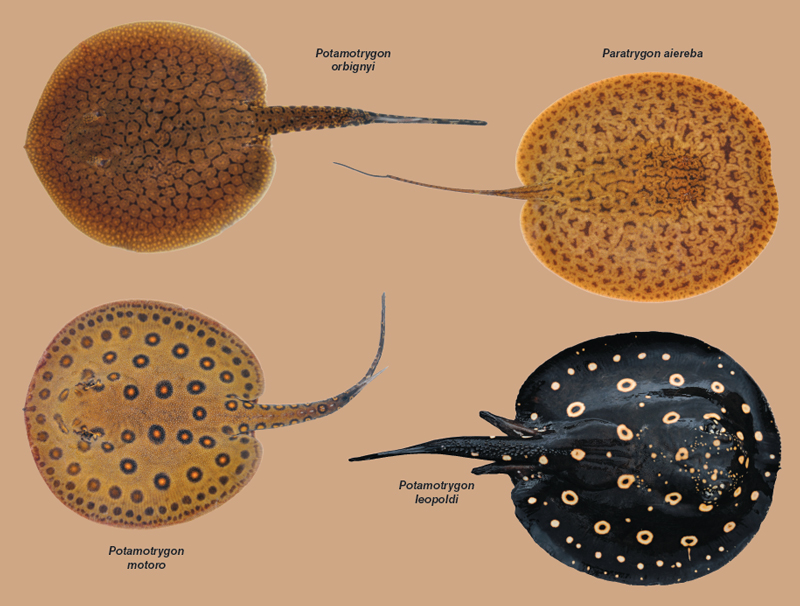

Plecos share dominion over the river bottom with freshwater stingrays, family Potamotrygonidae (above). River ray species in the lower Xingu exhibit four patterns of distribution that are repeated across many groups of fishes as well as some aquatic invertebrates. Generalist species, like Potamotrygon orbignyi, exemplify the first pattern and are distributed continuously throughout much of the Xingu and Amazon basins. Others, like Potamotrygon motoro, are restricted to lowland habitats below the Volta Grande rapids. Conversely, Volta Grande marks the downstream limit of many rheophilic (rapids-loving) and lithophilic (rock-loving) species, like Potamotrygon leopoldi. The fourth pattern is the replacement of a species occurring in Volta Grande and parts upstream, like Paratrygon “Xingu,” by a more cosmopolitan relative found widely in the Amazon, in this case Paratrygon aiereba.

Lowland diversity increases as one nears the Xingu’s mouth, especially for species widespread in the Amazon Basin or adapted to blackwaters supplied by the Xingu’s lower tributaries. The downstream leg of Volta Grande, with its swift, narrow channels, powerful rapids, and low waterfalls, acts as a faunal barrier or filter that impedes the upstream movement of many lowland fishes and other aquatic organisms. Species lost or replaced below Volta Grande presumably evolved on the Brazilian Shield, where rocky rapids dominate the Xingu. Their absence from the Xingu lowlands may be due to a scarcity of suitable habitat or an accident of drainage history. For example, the closest relatives of some Xingu fishes are found in the rocky Shield portions of neighboring basins to the east (Tocantins) and west (Tapajós).

Discontinuous distributions across modern drainage divides imply historical connections between basins. Biogeography and river geometry suggest that parts of the Tapajós, Xingu, and Tocantins were integrated into an ancient Shield river system separate from that of the early Amazon. Over time, that Shield system was dismantled as the Amazon Basin subsided and captured the lower courses of the Tapajós, Xingu, and Tocantins. Although hypothetical, such a scenario may also account for the abrupt faunal transition between Volta Grande and the Xingu lowlands. The Pimental Dam will add to the system’s discontinuity, particularly for widespread generalist species and migratory ones that seasonally move through Volta Grande.

Mark Sabaj Pérez

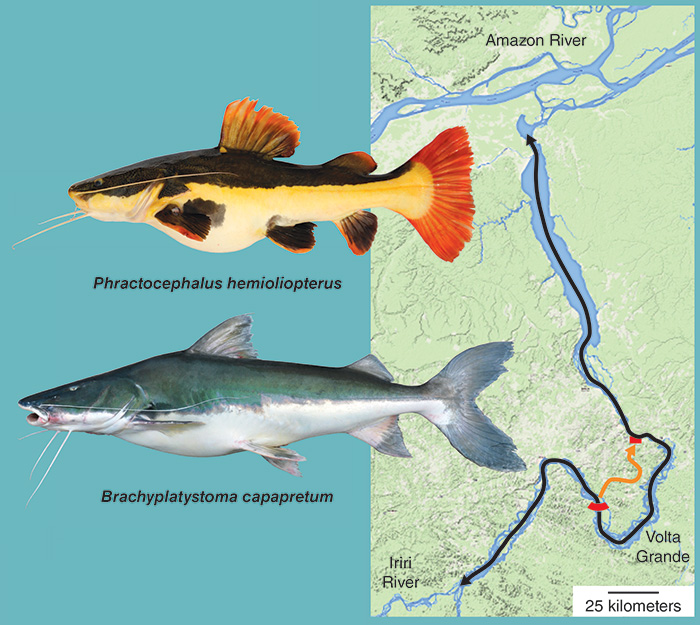

Long-distance migrants form one league of fishes that defy natural boundaries imposed by habitat or history. A team of Brazilians led by Lisiane Hahn is using combined acoustic and radio telemetry, or CART, to monitor the migratory movements of fishes along a 700–river kilometer stretch of the Xingu. Their preliminary data suggest that redtail and tiger-shovelnose catfishes (Phractocephalus hemioliopterus and Pseudoplatystoma reticulatum, respectively) migrate to distant upstream habitats during the flood season, presumably to spawn, and that Volta Grande is not a barrier to their movement. A venturesome redtail covered a distance of at least 329 river kilometers before escaping the limits of the study’s receivers (above).

The barrageiros have built a 1.2-kilometer fish ladder to help fishes circumvent the Pimental Dam, but the effectiveness of such artificial passes is highly questionable in tropical systems. For example, the concentration of migratory fishes in the fish ladder attracts a variety of aquatic and terrestrial piscivores, some of which take up residence in the confined passage.

During our own work in the high-water season, we captured an adult goliath catfish, Brachyplatystoma capapretum, in the rio Iriri near its confluence with the Xingu and upstream from Volta Grande. That catch, made using trot lines set overnight, was particularly exciting. Seven species of goliath catfishes are endemic to South American rivers east of the Andes. In the Amazon Basin, the young mature in the lower channel and estuary. Adults, which range in length from 0.5 to 3.6 meters, make long-distance migrations into the upper Amazon, ascending large tributaries to spawn in the Andean foothills. It was questionable whether adults entered the Xingu and its major tributaries. The rapids of Volta Grande are apparently no obstacles to such large and powerful swimmers. The ability of goliath catfishes to navigate a relatively narrow, 1.2-kilometer fish ladder, however, remains untested.

Despite fish ladders, captive breeding programs, and other mitigation efforts, Belo Monte will have a transformative affect on Volta Grande. When considering the impacts of a dam, people often focus on species extinctions. That view has some merit. If the impacted area harbors the only or the last remaining population of a species, it is certainly worth preserving. But in the case of Belo Monte, the loss of a few narrowly distributed species is trivial compared to the disruption of an entire system operating on such a grand scale.

We are not just losing dots on a map, a shorthand expression for the distributions of organisms documented by biological inventories. We are losing the extensive rapids, deep flowing channels, highly reticulate braids, and extremely variable flood pulses that contribute to the Xingu’s exceptional physical and seasonal complexity. We are losing the resiliency of a system that has been an incubator for aquatic diversity and evolution in large river rapids. The loss is especially acute because the Xingu is the second-largest clearwater basin in South America. The largest clearwater system, the Tocantins, was dammed in 1984.

Our efforts have been to document the complexity of the Xingu River as a baseline for future studies to measure the impacts of Belo Monte. Each new generation grows up in a world that is more engineered and less biologically diverse. As a result, baselines shift as new generations lose touch with what the world looked like and how it functioned before trampled underfoot. It’s hard for me to imagine a greater loss to the few remaining stretches of large river rapids. I hope our work will keep the memory of Volta Grande fresh and at the forefront of debate over future megadams. As long as rivers are made for dams, not biodiversity, barrageiros will certainly build them.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.