Picturing to Learn

By Felice Frankel

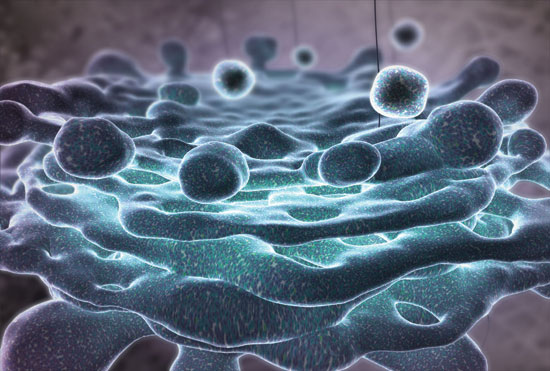

The Inner Life of the Cell is an eight-minute animation from Harvard's Biovisions Initiative

The Inner Life of the Cell is an eight-minute animation from Harvard's Biovisions Initiative

DOI: 10.1511/2007.64.166

"Makes you want to go back and take biology," commented Charles Gibson, anchor of the ABC World News, after the national news show aired a story about The Inner Life of the Cell (video linked below). "Inner Life," as it is referred to by its creators, is a knockout science animation unlike any other one sees these days, at least those produced for undergraduate education. The eight-minute piece was funded by a grant from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) to Robert Lue, who directs life sciences education at Harvard.

F.F. Rob, can you briefly describe what you set out to do when you first received the funding?

R.L. My goal with the Biovisions Initiative is to create more powerful ways to communicate ideas in biology. For some time I have felt that the potential of multimedia in biology education has yet to be fulfilled. Indeed, multimedia as a means of imparting biological information is years behind its use in entertainment and other areas. The support from HHMI finally allowed me to tackle this gap by combining high-quality multimedia development with careful pedagogy and rigorous scientific models of biological processes.

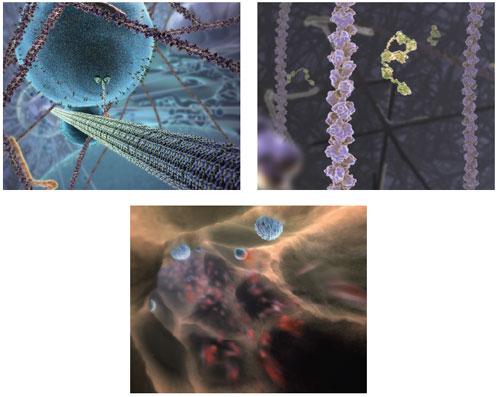

All images created by John Liebler of XVIVO and Robert Lue and Alain Viel of Harvard.

For this to happen, I needed to form a community of scientists, students and multimedia professionals. The Inner Life project was a proof-of-concept preview in which the conception and scientific content were co-authored by myself and a Harvard faculty colleague, Alain Viel, working closely with a remarkable animator, John Liebler, at XVIVO. This collaboration over more than a year is what enabled Inner Life to happen. I should point out that the version of Inner Life that has been released is a preview of a much longer animation with labels and narration that we will make available later this spring.

F.F. I've seen excerpts on a host of Web sites in addition to the TV piece. Why do you think Inner Life has received so much attention?

R.L. The attention and discussion illustrate the public's hunger for some way to understand what happens inside the body at the level of cells and molecules. The press is full of references to stem cells, small-molecule drugs and protein activity, yet these things remain abstract and mysterious to most outside of the sciences. Because the animation is a synthetic representation of cellular events that shows models for how molecules interact and behave in context, it serves as a window into this inner universe and imparts an intuition for molecular function that students and the public seem to find compelling. We chose to represent these events with an eye toward how best to teach and communicate a concept by ensuring maximum visual engagement.

All images created by John Liebler of XVIVO and Robert Lue and Alain Viel of Harvard.

F.F. You and I have talked about criticism from the science community about some of the animation's content. Here's your chance to respond to what some consider "incomplete."

R.L. We believe that the criticisms are based on a misunderstanding of what our animations are designed to achieve. They are not meant to be mirrors held up to reality. Rather than being simulations, our animations are representations designed to teach a very specific concept based on current science—models with a specific pedagogical goal. Each uses the actual structures of proteins when known, together with the latest models of how these proteins are arrayed and behave in the cell. As with any well-thought-out educational presentation, decisions must be made on what to show and what not to show, and on how the behavior of a particular element is portrayed.

All images created by John Liebler of XVIVO and Robert Lue and Alain Viel of Harvard.

For example, we have been asked why the protein monomers assembling into an actin filament (above) are not shown undergoing more random movements based on diffusion. The simple reason is that to show diffusion behavior risks obscuring the primary message, the polymerization of the monomers into a helical filament. Every sequence is the culmination of scores of such decisions, and when the animation is formally released this spring it will be accompanied by a storyboard and decision tree that will explain these choices—yet another important learning opportunity.

F.F. What plans do you have for more of this sort of work?

R.L. With support from HHMI, we are working on visualizations that dig deeper into several of the biological processes previewed in this first animation. Given the tremendous response, we hope to develop a dynamic archive of visual models that will grow and evolve as our understanding advances.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.