Invitation to an Insect Rendezvous

By Leila Christine Nadir

Artist Brandon Ballengée asks us to spend an intimate evening with bugs.

Artist Brandon Ballengée asks us to spend an intimate evening with bugs.

DOI: 10.1511/2014.107.146

They bite. They sting. They suck our blood. They can ruin agricultural crops, infest our kitchens, and chomp away at the foundations of our homes. And they are everywhere, crawling into the crevices of buildings, wriggling into our beds, hiding in dark corners. Insects, the most diverse and numerous organisms on Earth, comprise more than 10 million different species—perhaps, by some estimates, as many as 30 million. At any given moment, approximately one million trillion arthropods are creeping, burrowing, flying, and buzzing around our planet. For most members of the human species, these gazillion bugs are purely pests, best left unseen, and modern life has armed us with an arsenal of weapons—poisons, sprays, traps, zappers—to destroy them and, by extension, wipe them from our consciousness.

Despite most humans’ instinct to shudder at the sight of bugs, we need them. Entomologist E. O. Wilson writes, “If all humankind were to disappear tomorrow, it is unlikely that a single insect species would go extinct, except three forms of human body and head lice.” On the other hand, he continues, “If insects were to vanish, the terrestrial environment would soon collapse into chaos.” Without their services, flowers would cease to reproduce, most plant and animal species would go extinct, and humans would endure “widespread starvation” and “a tumultuous decline to dark-age barbarism … unprecedented in human history.” Wilson encourages us to put down our pesticides and change our attitudes: “More respect is due the little things that run the world.”

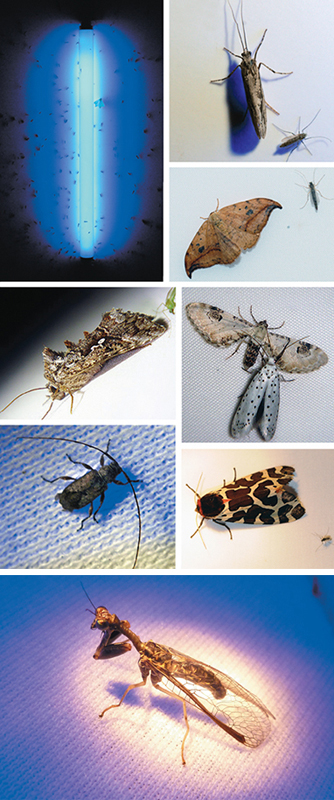

Transforming humanity’s vexed relationship to bugs has been one artist’s inspiration for creating a series of public art installations that encourage bugs to meet up, mate, and procreate. The pairing of visual creativity with scientific curiosity comes naturally to Brandon Balengée, who has exhibited his artwork in numerous presitigious galleries and public spaces throughout the world while also pursuing a doctorate in field biology. Ballengée constructs his installations out of eye-catching blue canvases, often shaped like insects or insect wings, and illuminates them by ultraviolet lights. As the sun sets, the structures begin to glow, attracting hundreds or thousands of nocturnal insects in search of a partner. Ballengée calls these artworks Love Motels for Insects, and he has designed them specifically to encourage people to watch the insects’ evening mating rituals.

The project began as an informal experiment more than a decade ago. Impressed with the biodiversity of the local tropical ecosystem during a trip to Costa Rica, Ballengée decided one evening to leave some bed-sheets and battery-powered flashlights on the forest floor to see what would happen. The results shocked him. Countless beetles, caddisflies, ants, lacewings, and other species appeared, and female moths left behind what Ballengée calls “paintings”: luminescent trails of pheromones released to attract mates. He found the experience so moving that he set out to bring this spectacle to the public. With Love Motels for Insects, people all over the world have been able to experience the charming qualities of amorous little bugs.

Since his Costa Rica experiment, Ballengée has installed Love Motels in shopping malls in New Delhi, on a boat in Venice, beside Aztec ruins in Mexico, on London rooftops, in New York City’s Central Park, and in a range of ecosystems, including forests, mountainsides, bogs, and marshes. He admits that occasionally some visitors run away in fear when the insects begin arriving on the scene, but much more often, distress gives way to admiration, aversion gives way to awe. Everywhere a Love Motel appears, human beings, eventually, are just as shocked by the arthropods’ diversity and the unexpected beauty of their one-night stands as Ballengée was that night in Costa Rica back in 2001.

Although the basic structure of Love Motels for Insects remains consistent, the installation never appears the same way twice. At each site, visitors observe local insect behavior and engage with landscape, biodiversity, and science in ways that are different every time. Sometimes the Motels coincide with festivals or concerts, picnics or film screenings. In New Haven, Connecticut, for example, Yale Peabody Museum scientists worked on identifying the mating insects while local artists created insect-themed graffiti. At each Love Motel, art and science collaborate, and bugs and humans come together, in recognition of the arthropods’ importance to life on this planet. The artistry extends beyond the physical object or installation, and beyond its visual beauty, into the unique events, interactions, and collaborations that result.

As much an experience as a physical installation, Love Motels for Insects works in the tradition of the 1960s Fluxus movement—an art movement that tried to break art out of the closed “white cube” of the gallery and into the public arena, often outdoors, where it could start discussion and stimulate the imagination of people on the street. Fluxus artists claimed their work had no singular mission, no specific message to disseminate; instead, they were attempting to create experiences, or “happenings,” that opened up participants’ eyes in some way. The artists left it to their audiences to decide what had occurred in the process.

To understand Ballengée’s Love Motels as part of the Fluxus tradition, German artist Joseph Beuys’s concept of “social sculpture” is particularly helpful. For Beuys, society is one artistic medium among many. The idea of social sculpture includes “how we mold our thoughts or how we shape our thoughts into words or how we mold and shape the world in which we live.” For Beuys, this type of art transforms the artist from his traditional definition as a creative genius into a facilitator of transformative events and interactions—just as Ballengée does each time he sets up a Love Motel. The artwork, rather than being a static object, becomes an opening of new possibilities and new ways of thinking and seeing.

As social sculpture, Love Motels for Insects sways the Fluxus impulse toward ecological concerns and scientific inquiry, engaging the public to challenge perceptions of insects as dirty pests. At the Love Motel installed in Delhi, India, Ballengée worked with local collaborators to create bilingual placards displaying statistical research that demonstrated the ecosystem services provided by insects: dragonflies as mosquito control, bees and butterflies as pollinators, praying mantises as predators of crop-eating insects. Many passersby were surprised to discover that creatures they had regarded as lowly and inconsequential provided such effective and sustainable alternatives to chemical pesticides.

Discussions of the importance of insect life to the planet’s ecosystems are a common part of Love Motel installations, as are new scientific revelations. At a Love Motel in Gongju, South Korea, professional entomologists from Gyeryongsan Natural History Museum identified three arthropod species that hadn’t been known to exist in that area. Because the public is so engaged with observing insects at Love Motel installations, such findings are often produced with the help of untrained citizen scientists, leading to a newfound awareness of ecological relationships. In Ireland’s Lough Boora Parklands, near Dublin, a Love Motel inspired visitors to examine arthropod species that may have returned to the park as a result of recent wetland restoration efforts. Ballengée has also trained a group of citizen scientists in New York City to collect Love Motel data. Some of their contributions to science have included the discovery that the most productive, or rather reproductive, time period for insects begins one hour after sunset and lasts for approximately ninety minutes.

Unless otherwise specified, images courtesy of Kevin O’Dwyer, from Exhibition at Aras an Chontae Gallery, Tullamore, Ireland.

It turns out there is a lot to learn from bugs. Fifty years ago, in Silent Spring, Rachel Carson encouraged her readers, including scientists specializing in agricultural insecticide production, to consider the complex roles played by six-legged animals in the “vast web of life.” Since then, entomologists are increasingly publishing popular books extolling the importance of insects not only to planetary ecosystems but also to better understanding humanity. Thomas Eisner makes one of the most compelling points: Insects, he writes, “have succeeded in one major respect where humans have failed. They are practitioners of sustainable development. Although they are the primary consumers of plants, they do not merely exploit plants. They also pollinate them, thereby providing a secure future, both for themselves and for their plant partners.”

Unless we rethink the tendency to kill insects rather than respect them, such lessons go unlearned. Ballengée’s hope is to create experiences and events that enable us to rethink our cultural climate—“to activate community, to make people learn something and become inspired, to cause them some increased awareness to help protect insects, to make people a more invested part of the natural community.” In the illuminated space of Ballengée’s Love Motel for Insects, participants have the chance to focus on insects they do not normally consider, either because it’s usually too dark outside to see them or because we have been conditioned to squash them before we take a closer look. In that moment of peering into the motel structure, to observe, concentrate, appreciate, and study—to think about the ecological threads that connect the lives of insects and humans—participants’ imagination can grow in new directions. That’s when the Love Motel turns into a social sculpture, and that’s where the art happens.

Watch a video that includes an interview with Dr. Ballengée and visuals from the July 2014 RTP180 event in Research Triangle Park, NC:

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.