This Article From Issue

September-October 2014

Volume 102, Number 5

Page 325

DOI: 10.1511/2014.110.325

To the Editors:

In the article “Can Skinny Fat Fight Obesity?” (July–August), the authors Philip A. Rea, Peter Yin, and Ryan Zahalka tell a wonderful and insightful story about brown fat cells. Forty years ago I married a woman who very seldom felt cold. I told her then that I thought she must have some brown fat, because I knew from my training in biochemistry that brown fat has more heat-generating mitochondria than white fat.

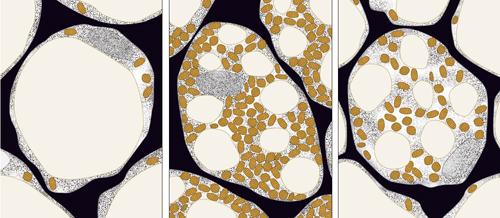

As the article details, so-called brown fat started appearing in medical images of adults in 2002. A white fat cell is made up of a single fat droplet with only a few mitochondria. In contrast, brown fat is rich in mitochondria, as illustrated on page 275 of the article (shown above), and contains an uncoupling protein, UCP1, which accelerates fuel consumption as well as releases energy as heat—instead of storing energy as adenosine triphosphate, better known as ATP.

The article also records that these beige-brown fat cells can switch from accumulating fat and burning it, depending on the metabolic needs of the organism at particular times. This strongly suggests to me that there is epigenetic control over this phenomenon, where genetic control is affected not by DNA but by, for example, alterations in the chromatin packaging of the DNA in our chromosomes. Do the authors agree?

Royden Hunt

Cardiff University, Wales

Dr. Rea, Mr. Zahalka, and Mr. Yin reply:

Yes, there is now evidence to indicate that not only do the sequences of the genes one is born with determine beige and brown fat content, but also epigenetic factors alter the structure of genes without changing their sequences.

Epigenetic factors, which can include DNA methylation and the chemical modification of chromosomal proteins such as histones that package DNA, are capable of explaining how cells with identical DNA sequences can differentiate into diverse cell types with distinct properties. In the case of the epigenetic control of the beige fat transition associated with the browning of white fat, Dr. Hunt’s question is especially timely, because some of the most compelling evidence for it was published in Nature Communications just last month.

A team led by Drs. Roland Schüle and Delphine Duteil of Freiberg University, Germany, has shown a direct link between cold-induced activation of an epigenetic enzyme, whose acronym is LSD1 for lysine-specific demethylase 1, and the browning of white fat. By stripping histone H3 of its methyl groups, this enzyme switches on a whole raft of genes that collectively contribute to the formation of beige fat cells from their progenitors. Under cold conditions, LSD1 ups the beige fat cell content of white adipose tissue to increase nonshivering thermogenesis. When animals are fed a high-fat diet, LSD1 also can diminish weight gain and predisposition toward the development of type 2 diabetes.

Therefore, one wonders whether there are at least two explanations (and perhaps many others) for why Dr. Hunt’s wife seldom felt cold. One is that she simply started off with more beige or brown fat than most of us because of the genetic hand she had been dealt. The other is that her epigenome was programmed by factors that took effect in her early youth (possibly perinatally or even prenatally) that forced her genetic hand by switching on a beige fat genetic program that many of us also have, but which is not epigenetically activated to the same extent.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.