This Article From Issue

May-June 2015

Volume 103, Number 3

Page 230

DOI: 10.1511/2015.114.230

COSMIGRAPHICS: Picturing Space Through Time. Michael Benson. 320 pp. Abrams, 2014. $50.00.

INFINITE WORLDS: The People and Places of Space Exploration. Michael Soluri. vii + 344 pp. Simon and Schuster, 2014. $40.00.

“When I behold the stars which thou hast ordained, what is man that thou are mindful of him?” Harvard science historian Owen Gingerich quotes from Psalm 104 in his introduction to Cosmigraphics—the latest from Michael Benson, author of Beyond and Planetfall—encapsulating in one line the grand theme of the 310 pages that follow. The vastness of the universe is both exhilarating and existentially terrifying. In response, artists and mapmakers have struggled to reduce the cosmos to a comprehensibly human scale, creating works of extraordinary beauty in the process.

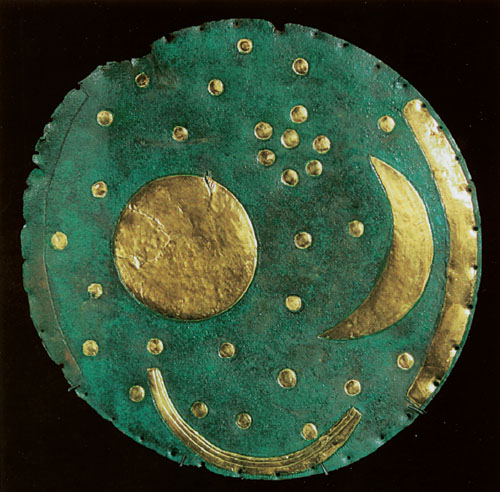

From Cosmigraphics.

That effort began long before art and mapmaking were even recognizably different things: The Nebra Sky Disc, the oldest known representation of the heavens, dates from approximately 2000 BCE. You will see it here, along with hundreds more celestial depictions running all the way up to the latest maps of dark matter and intergalactic structure. The illustrations are all full color, lavishly sized, meticulously reproduced, and almost indescribably gorgeous. I cannot ever recall getting shivers of pleasure so often simply by flipping from one page to the next.

From Cosmigraphics.

Benson’s accompanying text pulls off the hat trick of being simultaneously erudite, lyrical, and accessible. The author also proves himself a wily curator. Cosmigraphics is a comprehensive course in science history, covering the most famous astronomical drawings and images while also making room for quirkier creations, like a 16th-century map that transforms our planet into the face of a court jester, or an 1893 broadsheet that attempts to revive a flat Earth. There is no snicker in these asides. They reemphasize the vast range of ways the human imagination has attempted to come to terms with the incomprehensible.

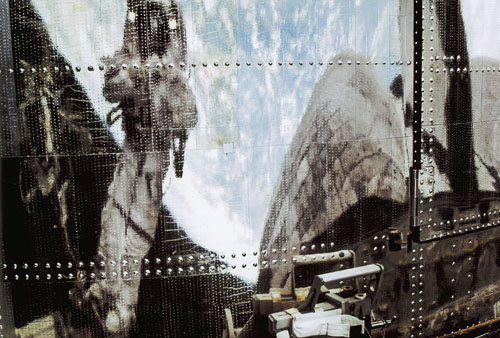

From Infinite Worlds.

Where Benson leaves off, photographer Michael Soluri picks up. His Infinite Worlds is a unique photographic chronicle of NASA’s 2009 space shuttle mission to repair the Hubble Space Telescope. (Full disclosure: I worked with Soluri and ran some of his photos while I was an editor at Discover.) That may sound like a more limited theme, but Infinite Worlds is every bit as grand as its title suggests. In an intriguing echo of Cosmigraphics, the book begins with a visual journey through the history of artistic abstraction, starting with the 75,000-year-old rock etchings of Blombos Cave in South Africa, before rocketing into the space age.

Even the photo essay at the book’s core is expansive and unexpected. Soluri’s roving lens captures rarely seen aspects of astronaut training in NASA’s Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory; the many unsung technicians and engineering innovations needed to support a major space mission; and startlingly fresh perspectives on the iconic space shuttle. And in a clever twist, the Hubble Space Telescope, humanity’s greatest eye on the universe, itself becomes the center of attention here.

From Infinite Worlds.

The shuttle program was discontinued and Hubble will be shut down later this decade, realities that lend an elegiac quality to Infinite Worlds. Mindful of these transitions, Soluri spent time teaching the astronauts to be adept photographers, hoping to spur more and better views from space. The outpouring of imagery from recent International Space Station crews testifies to the success of Soluri’s campaign. His effort also yielded the most memorable shot in the book: A self-portrait by astronaut John Grunsfeld, seeing himself in the reflection of the Hubble telescope, with the cloud-flecked Earth behind. It captures the terrestrial and the cosmic, the human and the infinite, all at once.

Corey S. Powell is senior consulting editor for American Scientist and former editor-in-chief of Discover magazine. His blog, Out There, appears at http://blogs.discovermagazine.com/outthere.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.