This Article From Issue

May-June 2022

Volume 110, Number 3

Page 184

THE SCIENCE OF LIFE AND DEATH IN “FRANKENSTEIN.” Sharon Ruston. 152 pp. Bodleian Library Publishing, 2021. $40.

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, first published in 1818, is literally about the meaning of life: not a meditation on the nature of life in general, but a specific meditation on a debate unfolding as Shelley was writing. The book is most commonly read as a warning about scientific hubris, or more broadly as a warning about the uncontrollable consequences of dangerous endeavors in any realm of human activity—say, the “Frankenstein’s monster” one might unleash by fanning the flames of white nationalism or antivaccination paranoia or some hideous combination thereof. The novel openly invites those readings; it is also a powerful meditation on loneliness and friendship, freedom and slavery, generosity and injustice, and the promises and dangers of polar exploration. But as Sharon Ruston’s brief and lively new book, The Science of Life and Death in “Frankenstein,” makes vividly clear, the novel is thoroughly informed by, and a serious contribution to, early 19th- century debates about what it means for a clump of matter to be “alive.”

Image reproduced courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University. From The Science of Life and Death in “Frankenstein.”

It is stunning that this aspect of the novel was overlooked and underread for almost 200 years. It was not until the 1990s that British scholar Marilyn Butler situated the novel in the context of the explosive debate that began in 1815 between John Abernethy and William Lawrence, who were both professors at the Royal College of Surgeons. Over the next five years, the two men alternated in giving an annual series of introductory lectures to medical students about the nature of life, lectures in which they argued about vitalism (Abernethy’s belief that there is some ineffable essence that distinguishes organic from inorganic matter and human life from all other forms of life) and materialism (Lawrence’s belief that life is just matter that somehow managed to replicate itself and eventually become sentient). Each year’s lecture series was promptly published, and Mary and Percy Shelley were acutely aware of this debate, as were most European intellectuals of their day, even the ones who called themselves poets. Lawrence was personal physician to the Shelleys, who were quite familiar with various radical ideas in the air—the idea that maybe God didn’t exist, for instance, or that all humans were truly equal and therefore it was immoral to use sugar because it was produced by slave labor. (They refused to do so.)

Ruston demonstrates that Mary Shelley was an incredibly intellectually voracious teenager, well informed about recent scientific developments in chemistry and experiments with electricity. (Many people assume that Victor Frankenstein shocks his creation into life—this is a staple of the films—but Victor himself is very careful not to disclose his method lest others try to replicate his awful results.) The novel notes that when Victor arrives at the University of Ingolstadt, he is enthralled by one Professor Waldman, who tells his students that science has discovered wonders such as “the nature of the air we breathe.” That would of course be oxygen, isolated and identified less than a half-century earlier in one of the more tangled episodes in the history of science (tangled enough to serve as material for Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions). The science Mary Shelley focused on was chemistry, but as Ruston points out, Percy Shelley’s editing of the manuscript changed “chemistry” to “natural philosophy,” a more general term for the natural sciences at the time. But in Mary’s mind, Victor was a chemist—not a medical doctor, or indeed a doctor of any kind, but a precocious student of chemistry who is for some reason allowed to work alone on a secret project for two full years.

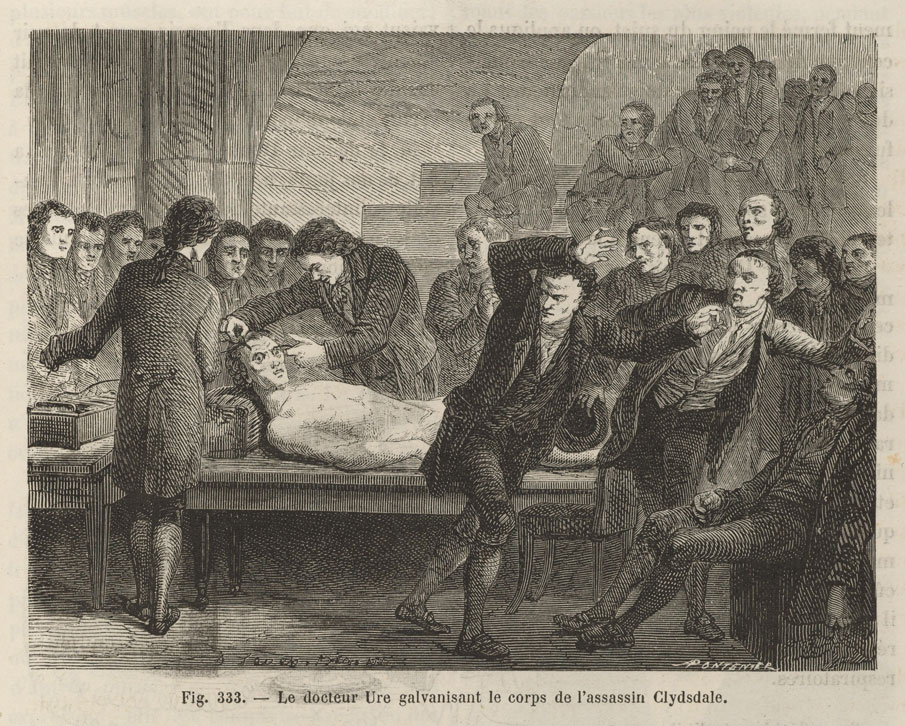

Ruston’s narrative is full of fascinating details. Although I knew that the era was one of extraordinary developments in the resuscitation of victims of drowning, leading many people to question the permeability of the boundary between death and life, I did not know that a critical ingredient in many such resuscitations was the insufflation of tobacco smoke into the rectum. Nor did I know that the 1752 Murder Act stipulated that the bodies of hanged murderers could be dissected by surgeons, which made it imperative to determine that the hanged murderers were actually dead and would not spring back into consciousness on the surgeon’s table (as some did, to everyone’s horror). Victor famously says, “Life and death appeared to me ideal bounds, which I should first break through, and pour a torrent of light into our dark world.” By “ideal bounds” he means boundaries that are not rigid, that are permeable; the sudden revival of apparently dead bodies, be they the bodies of hanged murderers or drowned innocents, led many people to wonder just how porous those boundaries are.

Ruston is especially good at explaining the high stakes (and high drama) of the Abernethy–Lawrence debate. It was framed in explicitly moral terms: Ruston explains that for Abernethy, a belief in “the vital principle . . . had moral, religious, and personal implications. Those who see life as the same in all living creatures, from humans to animalcules, would not be able to claim that there is anything especially moral or divine about humans, and this idea is sacrilegious.” Lawrence’s responses involved a surprising degree of snark and shade. In the second lecture that he delivered to the Royal College of Surgeons in 1816, on “Life,” he mocked vitalism by directly attacking one of Abernethy’s 1815 lectures to the same body:

This vital principle is compared to magnetism, to electricity, and to galvanism; or it is roundly stated to be oxygen. ’Tis like a camel, or like a whale, or like what you please. . . . It seems to me that this hypothesis or fiction of a subtle invisible matter . . . is only an example of that propensity in the human mind, which has led men at all times to account for those phenomena, of which the causes are not obvious, by the mysterious aid of higher and imaginary beings.

Ruston’s paraphrase is brutal: “Believing in Abernethy’s idea of life was tantamount, Lawrence argued, to believing that supernatural beings control our fate. He flew dangerously close to saying that believing in God is for idiots.”

Lawrence paid dearly for his audacity. He was stripped of his position in the Royal College of Surgeons (and thereby barred from practicing medicine) and forced to recant his 1819 book, Lectures on Physiology, Zoology, and the Natural History of Man. The materialist theory of life went into hiding until it was resuscitated, decades later, by debates over the origin of species.

Ruston argues that Victor bases his experiment on Abernethy’s premises: “Having worked out what the vital principle is and how to infuse it into a body, [Victor] then has to create a body to receive it. The practice set out here fits Abernethy’s theory entirely.” I’m not convinced. There is no indication that the Creature (as he is generally known these days) is animated by anything but sublunary forces; his life seems to be purely a matter of matter. For that matter, there is no hint in the novel of any God at all. In her introduction for the 1831 version of the novel (about which more in a moment), Mary Shelley described her initial vision of Frankenstein’s experiment as “frightful . . . for supremely frightful would be the effect of any human endeavor to mock the stupendous mechanism of the Creator of the world.” This is a familiar refrain, surely, to biologists and geneticists who are routinely accused of playing God. But no such phrase occurs in the novel: No one ever refers to “the Creator of the world,” and Victor never thinks in these terms.

Ruston notes that “whether the Creature has a soul is a vital unanswered question in Frankenstein,” and that the question “has been asked many times” since the novel’s publication. The pun on vital is clever, but the crucial point obscured here is this: Whether the Creature has a soul is a vital unasked question in Frankenstein. When the Creature tells Victor, “My soul glowed with love and humanity,” and when Victor says, “His soul is as hellish as his form,” no one is invoking the word in its religious sense. Frankenstein seems to me a thoroughly “materialist” book, even if Shelley herself changed her mind about that at some point between 1818 and 1831, as the political backlash against materialism intensified in the United Kingdom.

As for that 1831 revision: Ruston explains that she has chosen to work with the 1818 text “because this version contains more science. By 1831 the novel had become more overtly Gothic.” That’s a good call, but I would make it for a different reason: namely, Shelley’s decision to rewrite her novel so that it explicitly equates Frankenstein’s experiment with Robert Walton’s quest to reach the North Pole. “You are pursuing the same course,” Victor says to Walton in the later edition, “exposing yourself to the same dangers which have rendered me what I am.” This comparison is just plumb foolishness, since polar exploration isn’t anything like the creation of sentient life from dead matter; worse still, it has given rise to the popular misconception that the function of literature is to chastise scientists for pushing the edge of the envelope. In 1831, the novel goes from saying, in effect, “Victor should not have abandoned his creature,” to “People should just stay home and not inquire too much into stuff.” It’s not just that the 1818 version has more science; it’s that the 1831 version is actively anti-science.

Ruston notes that even though spectacular resuscitations were much in the news, “Mary’s decision not to use a corpse for the Creature [is] a particularly interesting one.” That it is: Victor cobbles together his creature from assorted human and animal bodies. I wish Ruston had said more about that decision—and more about Victor’s indefensible decision to experiment with the creation of life by starting at the top of the food chain. Surely an enterprising young chemist at the end of the 18th century could have become renowned and celebrated simply for giving life to a lab rat. It is odd that critics of Victor’s hubris don’t make this rather obvious objection to his work, and Ruston is especially well positioned to do so. But then, the story tells better the way Mary Shelley wrote it.

Editor's Note: An interview with the author of this review—in which he discusses Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein—can be found here.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.