This Article From Issue

September-October 2004

Volume 92, Number 5

DOI: 10.1511/2004.49.0

Mathematics in Nature: Modeling Patterns in the Natural World. John A. Adam. xxvi + 360 pp. Princeton University Press, 2003. $39.50.

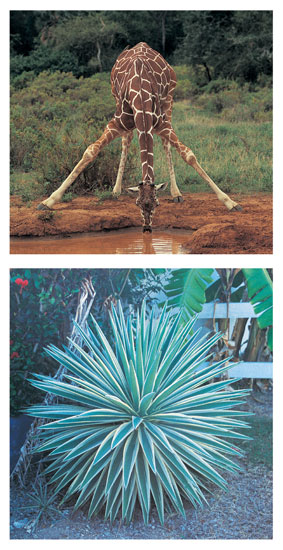

I've always loved math, and as a child I especially loved word problems about everyday things. The idea that the real world can be described mathematically was, to me, simply wonderful. Today I get the same enjoyment from mathematical descriptions of nature, which are just more complicated versions of the word problems I adored in my youth. A truly breathtaking range of such problems can be found in John A. Adam's Mathematics in Nature, which tackles quite a broad assortment of nature's patterns, going beyond the typical ones with which we might all be familiar. Most, however, are within nearly everyone's realm of experience. For example, the book's 24 color plates present fascinating cloud patterns, a double rainbow, sand dunes, ocean waves, plant and floral forms, patterns on animals and cracks in asphalt. Adam builds the reader's mathematical intuition as he discusses these phenomena.

From Mathematics in Nature

The word problems I was raised on dealt with a more select subset of experiences: bobs on strings, baseballs and missiles flying through the air, and cars accelerating on highways. Later the problem fodder got more diverse—but not by much. Even when I got to graduate school in physics, it was pretty limited. I recall once having a contest in a bar with some fellow grad students in which the goal was to imagine the most implausible scientific discipline. I came up with "theoretical biology." (Ironically, I'm now a professor of theoretical ecology.) Certainly my contest entry was the result of my own lack of imagination, but it was also a product of the limited scope of word problems I had faced during my education. A more diverse set would have given me, and other mathematically oriented students, a better sense of how broadly mathematics can be applied.

Mathematics in Nature is an excellent resource for bringing a greater variety of patterns into the mathematical study of nature, as well as for teaching students to think about describing natural phenomena mathematically. However, the book is not a light read for anyone who is not already well versed in the solution of partial differential equations. It could be used for an upper–level undergraduate course, or more likely a graduate–level seminar. It may be perfect for biology types who like math well enough but were immensely bored or put off by studying blocks sliding down inclined planes.

The initial chapters of the book define some terms, present guidelines and principles, and provide a warm–up set of two dozen estimation problems. These include such challenges as estimating "how fast human hair grows (on average) in miles per hour" and "the speed of descent of a cloud droplet in still air." I can't recall ever seeing these types of problems used so explicitly in any book; they're employed to overall good effect here.

I'm happy to report that dimensional analysis is given full coverage in a separate chapter on the problem of scale, with useful word problems to get the point across. I find that estimation and dimensional analysis are quite lacking in mathematical biology, particularly population biology and the dimensionally suspect concept of "population density." More attention needs to be paid to these features, but I've never known how to bring them up. That problem is solved here.

Next Adam examines various categories of patterns. Two chapters on meteorological optics deal with such subjects as shadows, rainbows, halos and the sun's reflection off rippled water. (I hadn't realized that a math problem lurked behind that last item.) These problems morph into questions regarding clouds ("How heavy is a cloud?" "Why do we see farther in rain than in fog?") and sand dunes, and there is an excellent discussion of hurricanes. Another chapter deals with all sorts of wave phenomena, bravely presenting a clear mathematical discussion of dispersion relations. This is followed by an excellent treatment of spatial stability analysis. These concepts, which involve some heavy math, are covered remarkably well.

A chapter on the Fibonacci sequence and the Golden Ratio represents a departure from the differential–equations mindset. A really sensible argument, based on efficient packing, is put forth for the striking seed patterns seen in sunflower heads—patterns that are based on the Fibonacci numbers. Adam then moves on to describe applications of packing to honeycombs, bubbles and mud cracks. After that, he brings differential equations back to discuss river meanders. Certainly many people have been fascinated with river meanders and the concomitantly formed canyons that can be observed from the sky. This work is then extended to tell you everything you've always wanted to know about trees—how they grow, bend, and filter light.

There is a short chapter on bird flight, and then the final chapter touches on biological pattern formation. The latter chapter is no match for what can be found on that topic in James D. Murray's book Mathematical Biology, now in its third edition. Murray provides excellent coverage of the application of reaction–diffusion models to biological pattern formation, and probably nothing will ever beat his presentation.

Adam could have included more patterns in his book. Ecological patterns are essentially absent (except for the implicit natural selection motivation for maximal seed packing in sunflower heads). Population dynamics, behavior, mating systems and evolutionary patterns—phenomena that constitute a huge part of theoretical biology—are not considered. However, the first three chapters alone make Mathematics in Nature an incredibly useful source for lecture material, and the breadth of patterns studied is phenomenal.—Will Wilson, Biology, Duke University

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.