Nanoviews: The Eighth Continent, The Oceans, and more . . .

By The Editors

Short takes on eleven books

Short takes on eleven books

DOI: 10.1511/2000.35.0

In The Eighth Continent: Life, Death, and Discovery in the Lost World of Madagascar (William Morrow/ HarperCollins, $27.50), Peter Tyson recounts with humor and honesty marvelous stories, discoveries and adventures from separate research expeditions to "Le Grand Île Rouge" with a herpetologist, a paleoecologist, an archaeologist and a primatologist. Drawing on history, biology, anthropology and paleontology, he explores the arrival of the island’s animals and plants, about 80 percent of which are endemic; their diverse speciation (shown is one of 62 chameleon species found on the island); the disappearance of unique megafauna, such as the nearly 10-foot-tall, half-ton giant elephant bird; and the origins of the Malagasy people. Madagascar has lost several species over the past 2,000 years, including the giant lemur, the giant land tortoise, the Malagasy aardvark and the pygmy hippo, as well as the elephant bird, and has been named one of the most threatened biodiversity hotspots. Working together on conservation, scientists and the Malagasy people have made notable progress despite their struggle with problems such as poverty, population growth and shrinking resources.

The Eighth Continent:Life, Death and Discovery in the Lost World of Madagascar

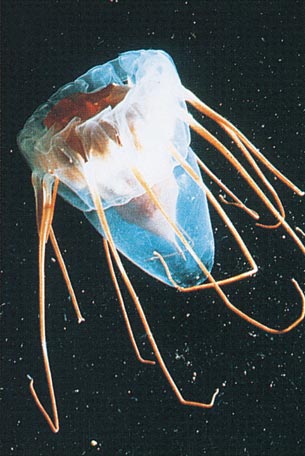

For lesser authors than Ellen J. Prager and Sylvia A. Earle, The Oceans (McGraw-Hill, $24.95) might more rightly be the title of an encyclopedia than of a 333-page book. Within this modest volume they have captured not only the physical and biological facts of the oceans but also their mystery, allure and even fragility. Although aimed at ocean oglers, rather than oceanographers, this work will offer anyone insights into the seas. Pictured is a gelatinous midwater creature.

Prides: The Lions of Moremi(Smithsonian Institution Press, $34.95) relates unexpected findings from a comparative study of four neighboring prides in northeastern Botswana. Pieter Kat's informative text and stunning photographs by Chris Harvey correct common misconceptions about these sleek predators. For example, lions prey on animals in their prime, not just the old, sick or weak; they often do not live up to their reputation as hunters (successful hunts can be the result of luck as much as strategy); and prides are loose associations based on familiarity, not tightly knit familial groups.

The Oceans

Cultures are sharply distinguished by their child-rearing practices. Here East and West do not meet; rather, social codes governing the "right way" to care for an infant form entire belief systems with remarkably little in common. This point is made in a clever and remarkably authoritative way in A World of Babies: Imagined Childcare Guides for Seven Societies (Cambridge, $49.95; $16.95 paper), edited by psychologist Judy DeLoache and anthropologist Alma Gottlieb. As the title suggests, between its covers a mother-to-be can get baby-care advice from a Micronesian version of Dr. Spock. She can either suspend her disbelief that a wise old Ifaluk woman would write a book chapter, or enjoy the notion of a gentle scholarly spoof of the very Western concept of a child-care manual. Pictured is an infant in Bali, where babies are viewed as gods.

Cultures are sharply distinguished by their child-rearing practices. Here East and West do not meet; rather, social codes governing the "right way" to care for an infant form entire belief systems with remarkably little in common. This point is made in a clever and remarkably authoritative way in A World of Babies: Imagined Childcare Guides for Seven Societies (Cambridge, $49.95; $16.95 paper), edited by psychologist Judy DeLoache and anthropologist Alma Gottlieb. As the title suggests, between its covers a mother-to-be can get baby-care advice from a Micronesian version of Dr. Spock. She can either suspend her disbelief that a wise old Ifaluk woman would write a book chapter, or enjoy the notion of a gentle scholarly spoof of the very Western concept of a child-care manual. Pictured is an infant in Bali, where babies are viewed as gods.

Feeling a little under the weather . . . but you’re not sure what might have caused it? In Was It Something You Ate?—Food Intolerance: What Causes It And How To Avoid It (Oxford, $25), science writer John Emsley and physician Peter Fell offer a readable introduction to some of the toxins, additives and contaminants that people often ingest (accidentally or otherwise) in the course of their daily meals. Beyond distinguishing food intolerance from food allergy (which is much rarer), the authors also offer insights into how eating a meal of several individually harmless items can provide a sufficiently toxic dose of a single chemical to do some serious harm. Included are some menus one might want to avoid.

If you lived through the years of Mercury, Gemini and Apollo, Failure Is Not an Option, by Gene Krantz (Simon & Schuster, $26), may well send a chill up your spine and bring patriotic tears to your eyes. Krantz, the mission controller who wore white vests and a crew cut, recaps his sometimes hair-raising personal experiences, beginning with America's first suborbital flight, through the tragedy of the Apollo 1 fire, the triumph of Apollo 11, and the near-disaster of Apollo 13. Despite a somewhat uneven text, the reader gets the sweaty-palm experience of the controllers (average age, 26) who had to make the split-second decisions that would put astronauts in the history books or kill them. This inspiring story of the Americans who sent men into space and brought them back is a Go.

A World of Babies; Imagined Childcare Guides for Seven Societies

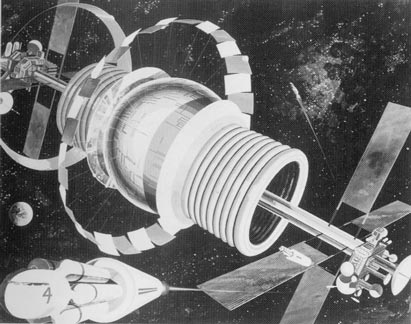

Science-fiction enthusiasts, among others, will find a nice summary of various ideas about the fate of our species in Our Cosmic Future: Humanity’s Fate in the Universe (Cambridge University Press, $24.95) by French astrophysicist Nikos Prantzos. The time scale ranges from our next baby steps into space to the physical evolution of the universe. Freeman Dyson meets Olaf Stapledon. Shown is the Bernal sphere, a design for a space colony near Earth.

It is often said that if the human brain were simple enough for us to understand, then we would be too simple to understand it. In The Private Life of the Brain: Emotions, Consciousness, and the Secret of the Self (John Wiley & Sons, $27.95), neuroscientist Susan Greenfield thoughtfully considers how our anatomically identical brains might be capable of creating the unique experiences and perceptions we recognize as ours alone. According to the author, emotions are the materials with which our individual minds are constructed; this model, like many in theory of mind, creates as many new questions as it answers.

Our Cosmic Future: Humanity's Fate in the Universe

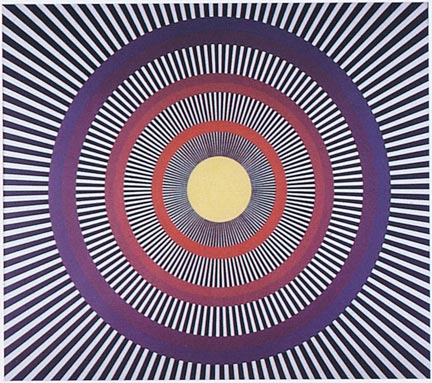

In Inner Vision: An Exploration of Art and the Brain (Oxford, $35), Semir Zeki attempts "to relate the func-tions of the visual brain to the functions of art." Zeki, who is well known for his research on the visual cortex, gives an up-to-date account of the functions of the cortical fields associated with aspects of visual experience such as color, shape and movement. He also writes perceptively about visual art from the medieval to the modern age. His exposition of these two very different lines of discussion is superb, but his efforts to integrate neurophysiology of the visual system and art appreciation—as he himself well realizes—are very much a work in progress. An understanding of the putative brain mech-anisms that add the aesthetic and emotional content to enjoyment of fine arts is apparently still far in the future. The book's many beautiful reproductions of art include the painting (Enigma, by Isia Leviant), in which the rings appear to be moving—an illusion associated with a change in local cerebral blood flow confined to area V5 of the cortex.

Inner Vision:An Exploration of Art and the Brain

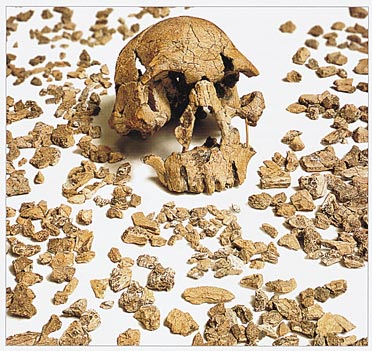

In Dawn of Man: The Story of Human Evolution (DK Publishing, $30.00), Robin McKie, a science journalist with The Observer in Britain, compares most of our evolutionary past to sitting at the Star Wars bar, because for all but the most recent period human beings were just one of several intelligent hominid species wandering about. This and other similarly evocative descriptions in the text fit with the many stunning photographs and attractive illustrations lavished on this book, which is published in conjunction with a documentary series airing on The Learning Channel. Shown is a Homo rudolfensis skull constructed from fragments found by Richard Leakey's team in Kenya.

How would the world's religions respond if intelligent life were discovered elsewhere in the universe? In Many Worlds: The New Universe, Extraterrestrial Life and the Theological Implications (Templeton Foundation, paper, $14.95), editor Steven J. Dick brings together 13 essays by various thinkers who consider whether traditional ideas about humanity’s relationship with God will change if we find out we’re not the only kids on the block. As one of the essayists, philosopher Ernan McMullin, asks, "Ought we expect these aliens to possess souls, and if they do, will some analog of the Christian doctrine of salvation apply to them?" The Church used to burn people for asking such things.

Dawn of Man:The Story of Human Evolution

Nanoviewers: Randy Black, Aili Petersen, G. G. Pinter, Rosalind Reid, David Schneider, David Schoonmaker, Rebecca Slotnick, Michael Szpir

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.