This Article From Issue

March-April 2009

Volume 97, Number 2

Page 169

DOI: 10.1511/2009.77.169

BARGAINING FOR EDEN: The Fight for the Last Open Spaces in America. Stephen Trimble. xiv + 319 pp. University of California Press, 2008. $29.95.

The strikingly beautiful Utah landscapes Stephen Trimble writes about in Bargaining for Eden—the craggy Wasatch mountain range, the desolate desert mesas—change subtly in appearance with each passing moment, as light and shadow dance over them. The same could be said of the book’s evolving perspective—every time I thought I understood Trimble’s position regarding the battles being waged over the precious wild lands that remain in the western United States, his point of view subtly shifted.

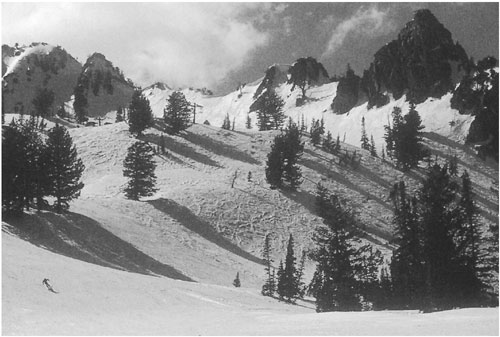

From Bargaining for Eden.

The first part of the book, aptly named “Bedrock,” sets the stage and sketches the main characters. The citizens of Ogden, Utah, are fighting billionaire oil magnate Earl Holding, who wants to transform Snowbasin, a community ski area on Mount Ogden, into a posh resort in time for the 2004 Winter Olympics. Trimble avoids the temptation to make this starkly partisan struggle into a morality play, perhaps because the story doesn’t end happily. Although the local environmentalists win a few battles, they lose the war, and the majesty of Mount Ogden is marred by development.

Rather than framing the Snowbasin saga as a tragedy, Trimble deftly uses it as a device for exploring a far more complicated theme, addressing himself directly to those who treasure wild land out West. They yearn for the romance, simplicity, community and connection they draw from open space and wilderness. Yet they also benefit from the roads, rural retreat homes and high-tech ski lifts that development provides. The poles of maximum development and maximum preservation are extremes at the ends of a continuum. Attaching oneself unthinkingly to either extreme creates destructive antagonism that severs ties to people and values on “the other side of the moral mountain.” A better, more sustainable approach to managing the lands of the West is needed.

Trimble’s openness to other people and their values makes Bargaining for Eden a compelling read. He colorfully traces the Snowbasin story, beginning with Holding’s purchase of the bankrupt ski area in 1984. To turn it into a megaresort, Holding wanted not only to gain control of the ski area base and the ski runs themselves, but also to develop land that was part of Wasatch-Cache National Forest. So he sought to have the Forest Service trade him a prime portion of the National Forest in exchange for other land that he would buy and add to the National Forest. Families in the area and environmentalists resisted him at every turn.

Initially, the local Forest Service decided to limit the land exchange to 220 acres. Administrative appeals were followed by mediation efforts and backroom negotiations, and the Forest Service increased the size of the exchange to 695 acres. Holding strategically delayed the land exchange to first secure a Forest Service permit allowing construction of new ski runs. A lawsuit filed by Save Our Canyons, a local environment group, successfully halted construction until adequate environmental assessment had been completed.

But in a climactic endgame, Holding exploited commodity-oriented Forest Service officials in Washington, D.C., found an eager ally in Republican congressman James V. Hansen of Utah, and took advantage of political pressure on the Clinton White House in the wake of the president’s designation of Grand Staircase-Escalante as a national monument. Through legislation sponsored by Hansen, promoted by Forest Service leadership and acquiesced to by the White House, Holding obtained1,320 acres of choice National Forest land. To avoid delays from further administrative appeals and lawsuits, the legislation exempted Forest Service actions implementing the Snowbasin land exchange from the National Environmental Policy Act, other environmental laws and judicial review. Additional special-interest legislation provided $15 million of federal funds to build a road connecting the Snowbasin resort to the interstate highway after Holding reneged on his promise to finance the road. The only glimmer of victory for the public interest in the whole saga came in 2000 when the Clinton administration finally held firm in refusing to allow Holding to build a tourist tram on lands transferred to the Forest Service as part of the Snowbasin land exchange.

Trimble concludes the Snowbasin story with a meditation expressing hope that Americans “are poised to enter a new New West—a twenty-first-century West, where the watchwords are ecology, ethics, relationships, collaboration, community.” Those words foreshadow the final section of Bargaining for Eden, which explains how Trimble’s personal experiences of the last few years have led him to embrace a new credo for managing Western lands. His reflections touch on such diverse topics as the role of the Mormon church in development, eco-spirituality, successful community resistance to Holding’s attempt to finance a $200 million hotel with public funds, the value of private land trusts, the difficulty of planning resource management given distrust between old-timers and newcomers, and the bittersweet victory of Clinton’s proclamation of the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument. Most of all, Trimble reflects on his own decision to build a retreat home on remote wild land in rural Utah. From all these experiences he distills a personal credo urging that local citizens use inclusive, respectful, collaborative processes to create a place-based vision and plan for sustainable land use management.

Although the stories of conflicts over resources that Trimble reports are intriguing and worthy of reflection, Bargaining for Eden suffers from defects that wear on the reader. The most serious is that Trimble’s uneven, impressionistic writing style and his decision to include many voices and perspectives combine to make it difficult to follow the progression and time line of the events he describes. Another problem is the intrusion of details of his personal journey into the material he has so conscientiously researched. His self-absorption is at times jarring and distracting.

Nevertheless, readers who persevere will be rewarded. The controversies Trimble describes are fascinating, his candid confessions of his own bargains with the devil of excessive resource consumption are engaging, and his distillation of the dilemmas confronted by those seeking to manage the West’s natural resources sustainably are insightful.

Susan L. Smith is a professor at Willamette University College of Law, where she teaches energy, climate change and natural resources law. She is the editor of Environmental Law Prof Blog (http://lawprofessors.typepad.com/environmental_law/) and writes extensively on sustainable resource management.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.