Making Better Maps of Food Deserts

By Anna Lena Phillips

Neighborhoods with little or no access to healthful food can be located and studied using GIS mapping

Neighborhoods with little or no access to healthful food can be located and studied using GIS mapping

DOI: 10.1511/2011.90.209

Food deserts—areas where consistent access to healthful food is limited or nonexistent—have gained attention recently. Michelle Obama has launched an initiative to end them in the United States by 2017. But in many areas, we still lack comprehensive, fine-grain knowledge of where food access is most challenging.

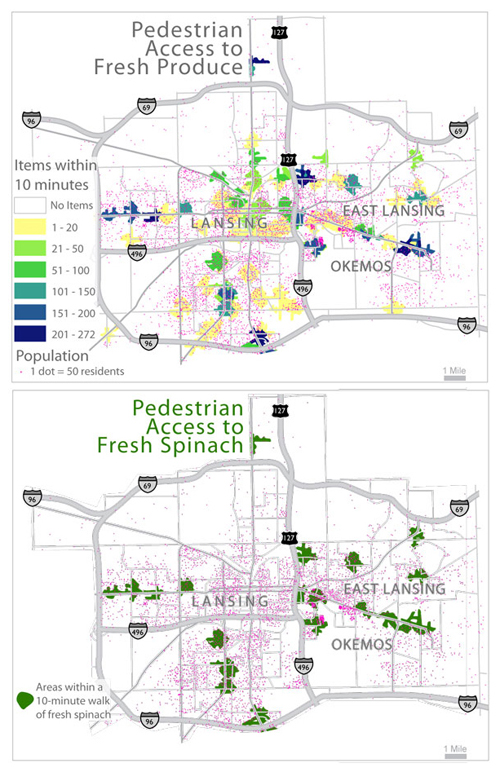

“It’s something that kind of snuck up on us as a scientific community,” says Kirk Goldsberry, a professor in the Department of Geography at Michigan State University. Goldsberry and his colleagues Chris Duvall and Phil Howard, also of MSU, have made a new series of maps showing access to fresh produce in the Lansing, Michigan, area.

The team wanted to measure food access using a deeper level of data than is often available. So, Goldsberry says, they visited every fresh-produce retailer in the area, locating 447 distinct produce items for sale. Then, using GIS (Geographic Information Systems), they mapped where each item could be bought.

Next they estimated routes and times that shoppers, both pedestrians and drivers, might take to the store, using a 10-minute walk (with an average speed of 3 miles per hour) and a 10-minute drive as their respective limits. Putting all the layers together yielded an interactive atlas of fresh-produce accessibility.

Jason Gilliland, a geographer at the University of Western Ontario who studies food deserts, likes the map’s design. “It’s one of the most visually appealing food-desert maps in terms of cartography,” he says. The atlas is already being used, says Goldsberry, to determine where to place community gardens. He hopes it will inform other community action and policy-making decisions, and that its techniques will be replicated. “We hope that people in Denver, Colorado, or people in Austin, Texas, see this map and say, ‘I want to see how my city looks through this lens,’” he says.

“Standardization of methods is critical for comparing results,” says Gilliland. Using higher-resolution data, as Goldsberry’s team has, is a good start. But Gilliland notes that we need better studies to help define map parameters. How long does the average pedestrian commute to a food source actually take, for instance? Alternately, maps could show availability in 100-meter increments rather than using a time limit. “Then you’d have a true accessibility surface,” he says.

And there are other factors competing for space on such maps. Something Goldsberry would like to add is change in availability of produce over time. In addition, maps would ideally reflect all the transit modes and food sources people use. So public-transit and bicycling data are valuable. Existing community gardens and food banks are important access points to include, Gilliland notes. And getting help from community members with data gathering can improve accuracy.

Then there are things that may not even be mappable, but that nonetheless affect people’s lives. “Much more goes into food access than can ever be captured by a GIS map,” says Tim Stallmann, a Ph.D. student in geography at the University of North Carolina and a member of the Counter Cartographies Collective. “There’s a whole dimension around money and differential access to stores, how different stores make different groups of people feel welcomed. There’s the amount of time folks have to go shopping in the first place, and when they have it.”

As geographers work to refine maps of food deserts, what can be done about the problem itself? A three-year study by Gilliland and Kristian Larsen, published in 2009 in the journal Health and Place, documented a 12-percent drop in average prices for healthful foods in an underserved neighborhood in London, Ontario, after a farmer’s market opened there. This decrease occurred even as prices at supermarkets in London rose by 9 percent.

Increasing access to healthful food could have dramatic results for public health. As Gilliland puts it, “We know you are what you eat, and that includes, you are where you eat.”

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.