Lost in Einstein's Shadow

By Tony Rothman

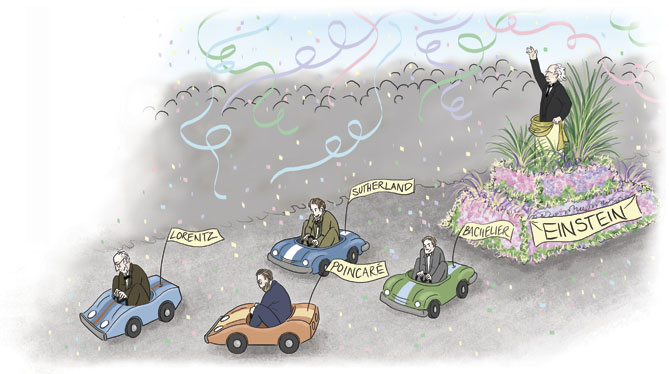

Einstein gets the glory, but others were paving the way

Einstein gets the glory, but others were paving the way

DOI: 10.1511/2006.58.112

Now that the worldwide celebrations marking Einstein's miraculous achievements of 1905 are over, let's take a moment to light a candle to the runners-up, those poor fellows who were hot on Einstein's heels, who almost got it right and perhaps would have, but who've been lost in the shadow of his great triumphs. It is true; Einstein was not the only person at the turn of the last century thinking about molecules and relativity. What's more, he was up on much of their work and, like any scientist, stood on the shoulders of his predecessors.

Stephanie Freese

The central fixture of Einstein lore is that the lowly patent clerk conjured from pure thought not only his theories but also the questions they answered. Not quite: Einstein himself helped foster this myth (more through carelessness than design, one suspects) by being less than fastidious about providing references in his papers, and since then credulous scientists have equated absence of evidence with evidence of absence. Physicists are notorious for taking history on faith, but none is required to prove this point—the evidence is in plain sight if one cares to look. The papers of Einstein and his contemporaries, as well as Einstein's letters, are published. Anyone who reads them quickly realizes that Einstein had a very good sense of the currents of science swirling about him and once or twice relied on the insights of colleagues.

Take the Australian William Sutherland, for example. One of Einstein's great 1905 papers explained "Brownian motion," the random jiggling of microscopic pollen grains suspended in water. Einstein proposed that the movements were due to collisions between the pollen and invisible water molecules and inferred from this the size of the molecules themselves. In doing so, he provided one of the final "proofs" of the existence of molecules, which in 1905 was still debated.

Sutherland was also interested in the motion of small particles suspended in liquids. In 1904, he proposed to the Australian Association for the Advancement of Science a method to calculate their mass. In March 1905—at exactly the time Einstein was working on his own paper—Sutherland submitted an improved version of his idea to the Philosophical Magazine, the leading English-language scientific journal of the day. It was published in June. In this paper, Sutherland derives the "diffusion coefficient," a number giving the rate at which particles move through a liquid. Moreover, he does so by exactly the same argument Einstein gives and arrives at exactly the same answer. Einstein goes on to use this number to derive the well known "diffusion equation." It tells him how far the particles will move in a given time, depending on the size of the surrounding molecules. A stopwatch and a microscope then allow him to measure molecular dimensions.

So, yes, Einstein went further than Sutherland, but Sutherland got one of the two crucial steps first. From letters to Einstein from his best friend, engineer Michele Besso, we know that the two men showed keen interest in Sutherland's work through 1903. After that, the discoveries were certainly independent.

In any case, a Frenchman, Louis Bachelier, scooped both Sutherland and Einstein. Bachelier was not actually interested in the twitching of suspended pollen grains. He was interested in the motion of prices on French stock market. But prices on the Bourse bounce around like pollen in water and their "random walk" can be treated mathematically like the diffusion of pollen in a liquid, which is exactly what Bachelier did in his remarkable 1900 doctoral thesis, "The Theory of Speculation." His paper is full of the jargon of economists, but Bachelier's equation giving the drift of prices with time is identical to Einstein's for pollen. Bachelier anticipated the Black-Scholes approach to options trading (which garnered its authors the 1997 Nobel Prize in Economics) and has been crowned by modern economists the "father of mathematical finance." Back then, though, academia ignored him, and it would be surprising if Sutherland or Einstein had heard of him.

Of course, 1905 is remembered above all for relativity. As a result of a famously vague statement in Einstein's own paper about "unsuccessful attempts to detect the motion of the Earth relative to the 'light medium'," pundits have long held that he was only dimly aware of the celebrated experiments that failed to reveal the mysterious medium—the ether—whose existence was synonymous with the "absolute space" implicit in classical physics. That is, sound waves travel in air, water waves travel in water; physicists naturally assumed that light required a medium in which to travel—the ether. The trouble was, a whole series of experiments designed to detect it turned up empty handed. It was these negative results that eventually led to relativity.

Did Einstein know about the vigorous search for the ether? Well, in an 1899 letter to his fiancée, Mileva Maric, Einstein mentions that he's written to renowned physicist Wilhelm Wein about Wein's review of the ether experiments, and that he's anxiously awaiting a reply. Einstein also read an 1895 paper in which Hendrik Lorentz (independently of two others) postulated his famous "Lorentz contraction"—that objects moving at high speeds actually shrink. That paper was all about the ether experiments, and Lorentz introduced the contraction precisely to explain their failure.

Lorentz was no amateur. The Dutchman was considered the leading physicist of his generation, and soon he and his colleagues were waging a well-published attack on the hypothetical ether and all its difficulties. In 1904 Lorentz tried to fix everything with his celebrated "transformations" that mixed up space and time in a way that—if true—would leave Maxwellian electromagnetic theory intact but shake the foundations of Newtonian physics.

Lorentz didn't know why his transformations should be correct. With relativity Einstein provided the explanation, but shortly before his death, he claimed to have known only about Lorentz's 1895 paper, not the later one containing the transformations. Memory is often too good to be true. In Einstein's very paper of 1905 he says, "we have thus shown that ... the electrodynamic foundation of Lorentz's theory ... agrees with the principle of relativity." This appears to be a direct reference to Lorentz's 1904 work.

Einstein didn't call his creation "the theory of relativity," but it was indeed based on two postulates, the first being the "principle of relativity," the supposition that any experiment done on a train moving with constant velocity should give the same result as an identical experiment done on the ground.

It wasn't Einstein's idea. The great French mathematician Henri Poincaré enunciated the principle of relativity at least as early as 1902 in his popular book Science and Hypothesis. We know from Einstein's friend Maurice Solovine that the two pounced on Poincaré's book, indeed that it kept them "breathless for weeks on end." It should have. In Science and Hypothesis, Poincaré declares: "1) There is no absolute space, and we can only conceive of relative motion; 2) There is no absolute time. When we say that two periods are equal, the statement has no meaning; 3) Not only have we no direct intuition of the equality of two periods, but we have not even direct intuition of the simultaneity of two events occurring in two different places."

These ideas lie at the heart of relativity, and it is hard to imagine that they did not have a profound effect on Einstein's thinking. But Poincaré not only speculated—he calculated, and in the same weeks that Einstein was writing his paper on relativity, Poincaré completed a pair of his own. The major one is quite remarkable. Mathematically, he has more than Einstein does. Among other things, he notes that time can be viewed as a fourth dimension (something Einstein doesn't do, by the way), he predicts the existence of gravitational waves 10 years before Einstein does and, perhaps most remarkable of all, he writes down an expression exactly equivalent to E = mc 2 several months before his rival. But he fails to interpret it.

Poincaré's paper, alas, is that of a mathematician. Right at the start he sets the speed of light equal to a constant, "for convenience." The second, and revolutionary, postulate at the basis of Einstein's relativity is in fact that the speed of light is always observed to be the same constant, regardless of the speed of the observer. Perhaps if Poincaré had been less a brilliant mathematician and more a dumb physicist he would have seen that the whole edifice stands or falls on this "convenience." He didn't.

Not long ago I had the opportunity to give a colloquium on these and related matters at a major university. Among the 50 or so physicists in the audience, not one had read Einstein's original papers, yet alone Poincaré's. As I said, physicists are notorious for taking history on faith. Such insouciance, though, has not stopped physicists from repeating for several generations the usual platitudes about the history of their field. One might make a case that science is inherently anhistorical—certainly recent editions of undergraduate physics texts are entirely bereft of meaningful history. But if the history of science has any relevance to the doing of it, surely it is to remind us that science is a collective enterprise and to engender in us a humble awareness that the landscape of science would appear very different had the vast unrecognized majority never existed.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.