Personalizing Pregnancy Care

By Jasmine Johnson

Artificial intelligence can improve rates of prenatal visits for people at higher risk of preterm birth.

Artificial intelligence can improve rates of prenatal visits for people at higher risk of preterm birth.

Although the reputation of artificial intelligence (AI) has declined due to evidence of racial bias in various algorithms, the technology also shows promise in improving equity in health care. For instance, during the COVID-19 pandemic, AI proved useful in tracking cases and predicting outbreak hot spots. This technological development is now being deployed in many ways that can benefit medical diagnoses, create adaptive interventions, and treat health disparities. One recent application has been in pregnancy care.

Yolande M. Pengetnze, a pediatrician and vice president of clinical leadership at Parkland Center for Clinical Innovation in Dallas, Texas, developed a model using AI to predict the risk of preterm births. One in 10 children is born prematurely (at fewer than 37 weeks of gestation) in the United States. Preterm births are associated with many maternal risk factors, such as race, insurance coverage, and access to care. The primary risk factor, however, is a prior preterm birth—yet the majority of women who have a preterm birth have never been pregnant before or never had a prior preterm birth. Pengetnze and her team’s AI model aimed to figure out what factors would be predictive for women without any history of preterm birth.

Parkland Center for Clinical Innovation

Social risk factors—such as income level, education status, and access to nutrition—are not usually captured in predictive models, but combine to make health outcomes disproportionately more challenging for communities of color. Women of color have more of these social risks, and predominately Black neighborhoods are also more exposed to environmental pollutants. These same neighborhoods often do not have good access to medical care; lack of proper nutrition and care, as well as maternal stress, have been shown to correlate with premature birth. Black women are more likely to experience adverse pregnancy outcomes than other groups. Preterm births are elevated even among highly educated Black women because of the accumulation of other social risks that affect their well-being. Most interventions have focused on clinical visits, but the most at-risk populations are missed in these interventions when they are not receiving regular pregnancy care.

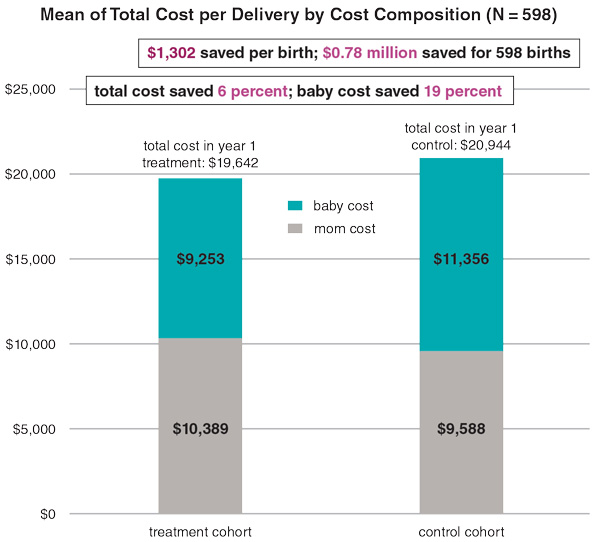

Preterm birth can lead to infant mortality; if the infant survives, they may experience feeding difficulties, developmental delays, and breathing problems. Preterm delivery also can cause financial challenges for families with limited resources, as costs for extended hospital stays and major developmental needs throughout life can become economic burdens, especially without social services support.

The research by Pengetnze and her team, as reported in the American Journal of Managed Care, used AI to bring together a comprehensive view of pregnant patients’ risk factors to create a risk profile. The model leverages machine learning and data from multiple sources—such as community data sets, insurance claims, census-based socioeconomic data, and clinical data—to predict preterm birth. Pengetnze and her team were able to train the AI system using data from a cohort totaling more than 6,500 patients; they then demonstrated the program on a test cohort of more than 2,700 patients. The researchers were successful at predicting preterm birth before 20 or 24 weeks—a crucial cutoff because interventions are more likely to work if providers can predict preterm risk early in the pregnancy.

Preterm births are elevated even among highly educated Black women because of the accumulation of social risks to well-being.

The risk profiles were given to the patients’ clinical providers to best determine their care plans. This full-view perspective allows providers to engage with their patients in getting the resources that they need. The risk profiles can shift blame away from patients who are at a higher risk because of structural racism in health care. According to Pengetnze, the risk profiles identify those subtle signs that wouldn’t be obvious even to trained clinicians. “As we talk more about health equity, it’s important that we have these kinds of risk profiles that combine both the clinical and the social risk, because we know that these are intertwined,” she said. “When we address those factors, hopefully we can bring some level of equity in the care that’s provided.”

Pengetnze acknowledges the ethical, equity, and justice concerns with AI development and applications. Algorithms have been shown to amplify biases in existing medical databases. Therefore, data of underserved populations are often skewed and not reflective of community needs. Researchers are working to achieve more algorithmic fairness, but Pengetnze points out that AI equity is achieved through looking for biases at every stage of development and identifying the sources of bias. “We always especially look at those potential risk factors that could be biased,” she said. “It’s important to keep in mind the fact that artificial intelligence has to be directed by insights and full knowledge of what’s happening in the community.” Increased representation and diversity in the AI field will also address disparities more accurately, she noted.

Parkland Center for Clinical Innovation

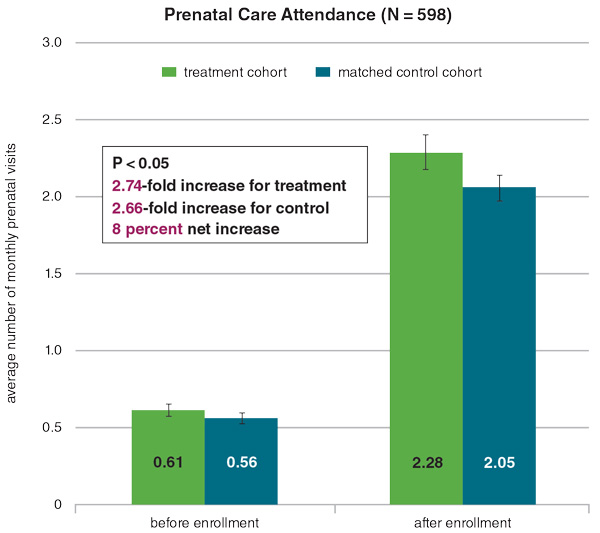

Pengetnze and her team have proven their risk profiles to be effective through an educational program that is tailored to each enrolled patient. The program’s personalized care experience includes risk-driven prioritized scheduling, text-messaging visit reminders, risk-driven education, and transportation assistance. This kind of social support has resulted in increased prenatal visit attendance. Going to the doctor more, lowering wait times, and supplying ride shares are all small but effective steps in reducing preterm births, Pengetnze noted.

With the recent Supreme Court decision to overturn the ruling of Roe v. Wade, reproductive rights have been left entirely up to individual states, which will lead more women to strongly consider their reproductive life plans based upon their zip code. Pengetnze notes that a customized care experience can be addressed at local levels with government officials, community organizations, and health providers because smaller providers or single-owned clinics may not have the logistics to implement large-scale social support programs.

Pengetnze and her team hope that using AI and digital technology will expand opportunities to improve patient outcomes. If racial biases in AI are addressed head-on, researchers could bridge known gaps in research. For instance, Pengetnze believes the way race and ethnicity are captured in data from insurance claims is still a concern. AI that is more user-centered opens spaces for increased patient engagement, and Pengetnze and her team have had their most successful outcomes when they centered the patient. Their system educates the patient and engages them in their own care to keep them proactively informed of the best-tailored interventions for them.

Other communities could implement similar programs that are created specifically to their needs, Pengetnze said. “Our next step is looking forward to expanding this and implementing this on a larger level, engaging more providers, engaging more health plans, and engaging more safety net health systems to try to implement these programs,” she says, “so that we can move from a singular clinical view to a more comprehensive social and clinical approach to addressing preterm birth prevention.”

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.