This Article From Issue

July-August 2013

Volume 101, Number 4

Page 268

DOI: 10.1511/2013.103.268

In the early 1960s some artists abandoned the wall, the gallery and the museum for altering the landscape outside. That’s what human beings had done to the Earth for millennia—left their mark, indelible or not. This may signal ownership, dominance or an attempt to connect or infuse nature’s power into the human creature. Or it may be a form of creative play, now augmented by machines.

However, a question arises these days about how environmentally aware and conscientious are land- or Earth artists? Five major figures and five key works help us assess the evolving role of environmental consciousness in Earth art. Two recent events in Los Angeles prompt me to make such an assessment: the installation of Michael Heizer’s rock, Levitating Mass, at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and a complementary retrospective, Ends of the Earth: Land Art to 1974 at the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA). In this, the fourth in a five-article series, I explore these works and attempt to answer that question.

My review of iconic Earth art works cannot report that any one of them has a particularly environmental or ecological theme. Smithson’s Spiral Jetty, Christo’s Umbrellas and Goldsworthy’s Storm King Wall certainly make us aware of the materials and forms of the natural world but primarily draw attention to themselves as art rather than emphasize an environmental purpose. Only in their eventual stately disappearance might they evoke or embody that.

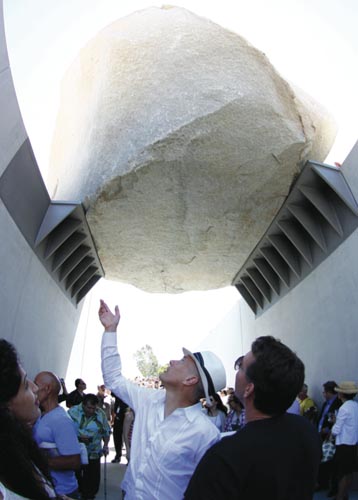

Michael Heizer’s Levitated Mass (2012) at the Los Angles County Museum of Art (LACMA) presents a different environmental ethic—monumentality and displacement as forms of environmental consciousness. Heizer had his eye on this giant granite boulder for 20 years and finally acquired the money and technique to have it paraded like a captured beast to the museum. In fact this 105-mile night-by-night journey was a key component of the work. The rock’s transport from a Riverside quarry through Long Beach onwards to the LACMA site on Wilshire’s Miracle Mile near the La Brea Tar Pits constitutes what we might call civic processional art.

Ted Soqui/Corbis

Like some triumphal progress through a grateful city, the citizens welcomed the vanquished trophy rock in the spirit of conquest and fun. It was not really clear what it memorialized, but thousand of people came out to cheer its slow, deliberate passage through the streets. If anything was “levitated,” it was the mood of the nightly enthusiasts en route. They were having fun with everything: with its package wrap; with the multi-wheeled linked carriages under which the rock was slung; with the raising and lowering of wires so the cradled rock could pass under; and with the parade stops at different parts of the 22 cities it traversed. (Crowds were not as charmed by the procession later in the year that required the chopping down of sidewalk trees to tow the space shuttle Endeavor 12 miles from L.A.’s airport to a final resting place at the California Science Center.)

But once installed on the 465-foot walkway that slants deeply under it, what could Levitated Mass commemorate? Like shaped Stonehenge, this quasi-raw megalith has an inscrutable purpose. It didn’t seem to levitate at all; the very visible cleats securing it underneath were judged both too big and likely to fail in an earthquake. The public scorned it as a fraud, a waste of money (however private), “a leviathan mess,” “a Rocky Horror.” Mostly it wasn’t art; it was engineering, crazy expensive $10 million engineering, in a city and state being squashed by a massive rock of debt.

Some did find it intriguing—as, for example, a contrast to the Higgs Boson that was confirmed about the same time, the gigantic massive rock taking the stage with the infinitesimal mass-creating particle.

Gene Blevins/Corbis

But few identified it as Earth art. In that framework it seems obvious as the return of a long-banished chunk of nature to the paved paradise of Los Angeles. Its displacement from its natural setting makes its contrast with its built surroundings even more dramatic, and its size and weight, its monumentality, at least from below, tries to dwarf the viewer by inducing an awe-struck wonder.

But it does seem an environmental dud. Its effect on its surroundings is minimal. Poet Wallace Stevens in “Anecdote of the Jar” (1919) imagines the shaping influence of a simple glass jar placed, or displaced, to a woodsy setting:

I placed a jar in Tennessee,

And round it was, upon a hill.

It made the slovenly wilderness

Surround that hill.

The wilderness rose up to it,

And sprawled around, no longer wild.

The pure form-giver jar reshapes and tames the wilderness simply by its presence on a hill, drawing scruffy nature into its hard, circular energy field. Heizer’s near-wild rock might have had a valuable reverse effect.

But Levitated Mass does not reshape the suburban environment or the off-site apartments and skyscrapers that frame it nearby. It sits open and exposed in an overly large playa of crushed rock, and seems forlorn, stuck in limbo, a boulder bolted to a cement pedestrian channel with no connection to its original source, unable to return the city, or itself, to the wild. Its “Levitas” shape-shifts into “Gravitas,” floating into sinking, fun into somberness.

There’s something iconic about this destitution—as if Earth art itself has reached a sort of dead end, stranded in a museum exhibit yard. Perhaps it’s L.A., perhaps it’s Heizer who doesn’t mind moving big pieces of nature around for the fun of it; perhaps it’s us, who wonder just what our relationship to the Earth has become now that we are much more aware of our deleterious effects.

Are we happy modifying it, reshaping it, stamping it with forms and decorations, and garnishing it with cloth and curiously designed add-ons in stone, steel and cement, and appreciating it as art? We could say in a nasty frame of mind that our most influential Earth arts are the garbage pits and toxic wastelands and fanciful faux-remakes of natural environments in our theme parks, resorts and casinos. Is the rock a big chunk of museum lawn art? Worse, is Earth art now uncool, un-green? Could that be Heizer’s subversive point?

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.