This Article From Issue

May-June 2003

Volume 91, Number 3

DOI: 10.1511/2003.44.0

The Eye of the Lynx: Galileo, His Friends, and the Beginnings of Modern Natural History. David Freedberg. xii + 513 pp. University of Chicago Press, 2002. $50.

In the first decades of the 17th century—so the old story goes—Galileo Galilei led a struggle to replace the sclerotic natural philosophy of the Middle Ages, entrenched in European universities and the hierarchy of the Catholic Church, with a new science based on mathematics and observation, not blind adherence to authority. In 1611, Galileo was invited to join a small scientific society, the Academy of the Linceans (Accademia dei Lincei). Founded in 1603 by Federico Cesi, this society would be almost unknown today had its handful of members not decided to stand by Galileo as his telescopic observations, and the conclusions he drew from them, became increasingly controversial. Members of the academy helped plan Galileo's strategy for dealing with the Roman curia; they celebrated his victories, consoled him in his setbacks and cautioned him—usually unsuccessfully—to be prudent. His condemnation as a heretic in 1633 was a defeat for the society, not merely its most famous member.

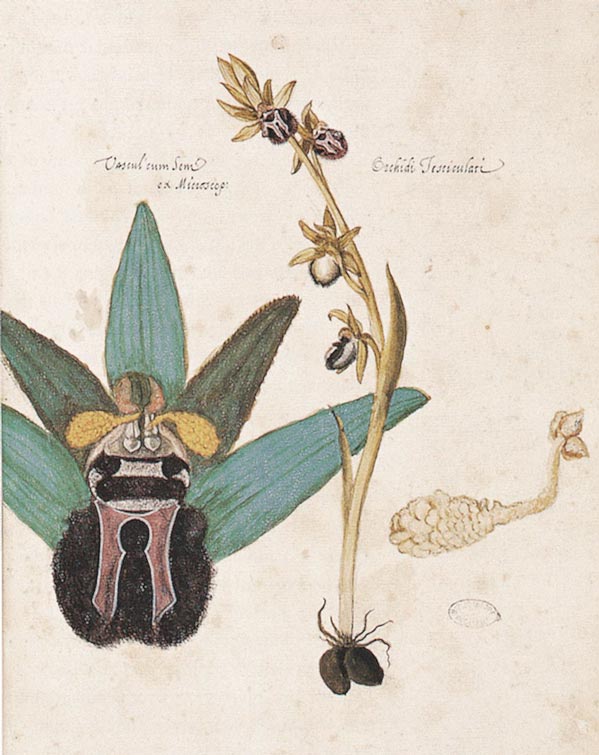

From The Eye of the Lynx.

But the Linceans were far more than Galileo's sidekicks. In a book that is part art history, part history of science and part detective story, David Freedberg has uncovered the vast range of the Linceans' scientific activities. His detective work began in 1986, when he discovered a large collection of 17th-century natural history drawings at Windsor Castle. These led him to their original collector, Cassiano dal Pozzo, a Lincean, and thence to several other collections of natural history manuscripts that once belonged to Cesi or other members of the Academy. On the basis of these manuscripts and the few Lincean works that saw the press, Freedberg has reconstructed the world of Lincean scientific thought.

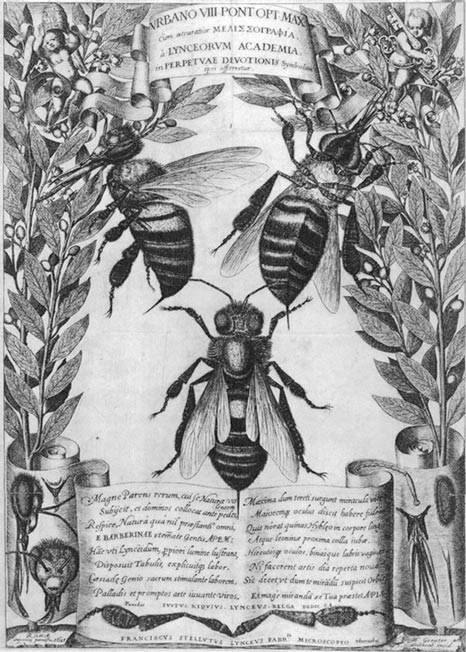

At the center of that world was natural history. Cesi and his fellow Linceans devoted countless hours to carefully observing and meticulously describing the plants, animals and minerals that they found on their journeys throughout Italy and the rest of Europe. They employed talented, sometimes brilliant, artists to record those observations in the albums that originally drew Freedberg's interest. They focused their attention not only on the surface appearance of things but also on their interiors, particularly the organs of fructification and generation. And they went beyond 16th-century predecessors such as Conrad Gessner, who also drew and dissected the parts of plants, by employing a new instrument: the microscope, which Galileo introduced to them. His telescopic observations forever changed how we understand the heavens; the Linceans hoped that their microscopic observations would do the same for the terrestrial world.

From The Eye of the Lynx.

Their efforts generated thousands of illustrations. The Lincean corpus contains at least 2,700 drawings, some of which are reproduced, for the first time, in the pages of Freedberg's book. It dwarfs other contemporary collections of natural history illustrations. The pictures range in subject from the prosaic to the exotic, from the normal to the monstrous. Yet the long series of ferns, fungi, strange fossil woods and other peculiar objects reveal Cesi's obsession with what he called "middle natures," objects that appeared to combine the characteristics of two different natural kinds. Fossil wood was an example: It had the form of a plant, but it was made of stone. Cesi hoped that these ambiguous objects would be the test cases for an authentic classification of nature.

But the more Cesi looked at images, the more he came to realize that their welter of detail ran counter to his classifying impulses. In The Assayer (1624), Galileo taught his fellow Linceans that real science required penetrating the surface appearance of things not with the microscope but with the mind. Cesi concluded in his later works, few of which were ever published (he died in 1630), that observation was only one moment in the process of scientific investigation, and that it had to be disciplined by knowledge. To observe—not merely to see—one needed first to know which characters were essential and which should be ignored. Cesi thought hard about how to tell them apart, but he never succeeded.

Freedberg is at his best when, like the Linceans, he is absorbed in details and engaged in close analysis. This is a long book, but it is carefully written, and the slight repetition serves only to remind the reader of important elements in the argument. Each of the 172 illustrations contributes to Freedberg's analysis; although they are often beautiful, they are not mere decoration. The Eye of the Lynx delivers on its promise to offer the first book-length study of the Linceans in English, and it does so with sympathy and empathy for its subjects.

Freedberg is less successful at placing the Linceans in the context of the Scientific Revolution as a whole. He sometimes exaggerates how innovative they really were. By paying attention to visual detail and the variety of nature, the Linceans were continuing a 16th-century tradition, although they addressed problems their predecessors had neglected and used a new instrument. But Freedberg has little sympathy for 16th-century science, which he characterizes as reactionary, occult, confused and anthropomorphic. The difference between the old and the new is epitomized for him by the difference between Galileo, the sixth Lincean, and his immediate predecessor as a member, Giovanni Battista Della Porta. Galileo's science was based on experiment and mathematics; Della Porta's was a pseudoscience based on surface appearance and vague similarities between objects. When the Linceans veered in Della Porta's direction, they were backsliding.

But why was Della Porta invited to join the society in the first place? The answer reveals a more nuanced view of Renaissance science. Like Galileo, Della Porta opposed the Aristotelian science that dominated the universities of Renaissance Europe. Renaissance Aristotelians offered a qualitative explanation of the way Nature behaved in general. They simply threw up their hands when confronted with "occult qualities" and "jokes of nature," apparent exceptions to nature's regularities. In contrast, Della Porta, the German alchemist Paracelsus, Girolamo Cardano and other 16th-century anti-Aristotelians focused their attention on natural particulars: the way Nature behaved in specific instances, often those that seemed to reveal her most subtle workings. They recognized that a new science would have to account, somehow, for these exceptions to the way the world normally worked.

Cesi's fascination with middle natures fits in with this aspect of Della Porta's concerns. But Cesi also learned from Aristotelians: His emphasis on the role of reproductive organs in classification drew heavily on the work of Andrea Cesalpino, whose On Plants (1583) was firmly in the Aristotelian mold. Like Galileo, Cesi in his mature work strove to combine the Aristotelian commitment to theoretical explanation with Della Porta's commitment to the careful investigation of particulars. Galileo would succeed by radically restricting the particulars to be explained to those qualities that were amenable to mathematical analysis—weight, extension and motion. Cesi would fail, but he was working on the right problem. His faith in pictures led him to recognize the problem, even though recognizing it ultimately destroyed his faith in pictures. As Freedberg tells it, the Linceans' story is full of tragedy. But by telling it with grace and empathy, he has also revealed its enduring element of triumph.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.