This Article From Issue

July-August 2003

Volume 91, Number 4

DOI: 10.1511/2003.26.0

Science in the Service of Human Rights. Richard Pierre Claude. viii + 267 pp. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002. $42.50.

Science in the Service of Human Rights is a timely book. In the past few months, we have witnessed a war predicated on one nation's possession of nuclear, chemical and biological weapons of mass destruction. In Iraq, before the bombing even started, scientists were questioned by United Nations weapons inspectors in the presence of Iraqi officials, despite protests from the inspectors, who feared that this might prevent the scientists from speaking freely. War raises enormous questions about responsibility and risk, about commitment and collaboration, and science is no stranger to these issues.

War is not, of course, the only context in which science and human rights come into conflict. In 2001, a slew of ethical and political issues were raised by press reports that the Chinese government harvested vital organs from executed prisoners and sold them to patients in other countries. Some Americans with renal failure have circumvented U.S. laws against the sale of vital organs by going abroad to undergo transplantation with a purchased kidney. Are the doctors who provide them with aftercare when they return to the United States morally implicated in the global organ trafficking that victimizes the poor and ignorant in the developing world?

What are the responsibilities of physicians and scientists? What are the sources of these responsibilities? How can science promote the protection of human rights, and how can human rights uphold scientific freedoms? Who should benefit from scientific progress? These are some of the questions that Richard Pierre Claude addresses in this brief but cogent book. Claude, a professor emeritus of government and politics at the University of Maryland and the founding editor of Human Rights Quarterly, provides a historical introduction to and framework for articulating the multiple and overlapping connections between science and human rights.

From Science in the Service of Human Rights

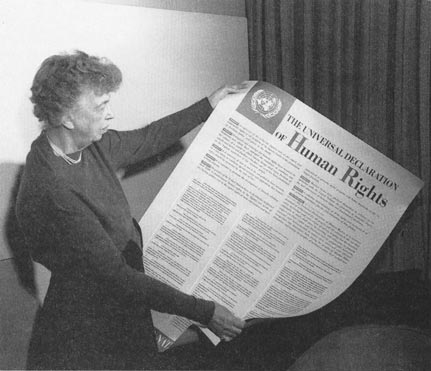

He begins with the Second World War and the efforts in its aftermath to prevent future catastrophic failures of diplomacy. Acting on the assumption that governments who respect human rights do not wage war against one another, countries in the newly created United Nations adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948. Claude provides a fascinating glimpse of the road to the Declaration, including the conflicts between the American delegate, former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, and the Russian delegate, Ambassador Alexei Pavlov (nephew of Nobelist Ivan Pavlov), who specifically warned about American mobilization of science for military purposes. In the harsh light of the atomic battlefield, science, as Claude points out, became an explicit focus of the framers, who drafted a provision stating that "Everyone has the right . . . to share in scientific advancement and its benefits."

Since 1948, provisions of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights have been reaffirmed in court decisions, treaties and international covenants. Claude traces the ongoing efforts of policy makers to implement, or avoid implementing, those provisions. Some of these efforts take place within a single country; others cross borders and raise questions about international cooperation and contention. One country's "bioprospecting," for example, may be another's "biopiracy" when it involves appropriating the knowledge, information or even genetic material of indigenous peoples without compensation or regard for the conservation of local resources. Concern for members of the general public and their right to share in the benefits of scientific advances is balanced by discussion of violations of the rights of scientists, whose work, freedom and existence have been threatened when their research has clashed with the dictates and expectations of powerful government officials.

The Declaration called on member nations to promote the distribution of scientific benefits for all citizens. The UN framers were equally ambitious in calling for international standards for interpreting the right to health and the right to medical care. Claude shows how the "Doctors' Trial" at Nuremberg, which exposed Nazi atrocities in medical experimentation and genocide, contributed to standards of medical ethics reflecting the norms of human rights. He traces the emergence of the World Medical Association and its efforts to promote new ethical guidelines for physicians and clinical researchers, including the Declaration of Geneva (1948), a revised Hippocratic Oath. Unfortunately, here Claude's discussion largely overlooks the difficulties and moral complexities in this association of diverse national medical organizations, difficulties that have compromised society's ability to speak with conviction for patient, rather than professional, welfare.

Much of the book makes for grim, if essential, reading. Stories of the torture of human rights activists, the abduction and adoption of Argentinian children whose parents had been murdered, and the repression of scientists seeking to uphold human rights overwhelm the descriptions of the counterefforts, such as the free provision, by volunteers, of psychiatric care for thousands of victims of torture; statistical efforts to demonstrate that women were systematically raped in Bosnia and Herzegovina; and forensic efforts to help the families of missing loved ones learn the nature of their deaths. This book helps us to understand how far we have come since the bleak days of the Second World War—and how far we need to go in the years ahead.—Susan E. Lederer, Section of the History of Medicine, Yale University School of Medicine

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.