The Complex Rise of Baleen

By Katie L. Burke

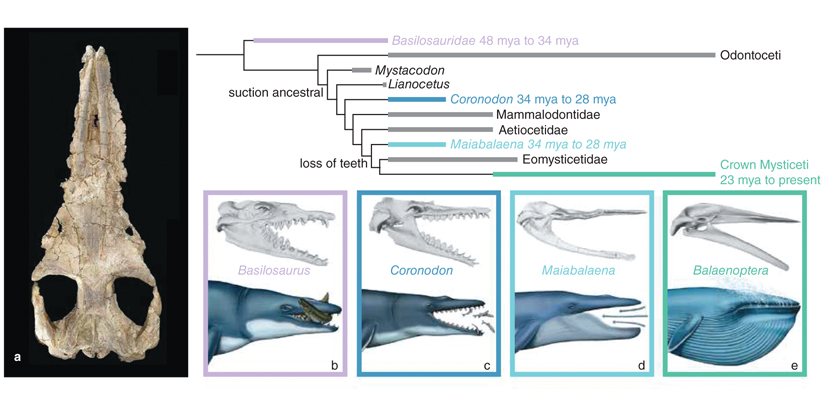

A 33-million-year-old whale fossil is a big piece in puzzling out the evolution of filter feeding in marine mammals.

A 33-million-year-old whale fossil is a big piece in puzzling out the evolution of filter feeding in marine mammals.

DOI: 10.1511/2019.107.1.8

“Is this crazy?” Carlos Mauricio Peredo wondered to himself as he repeatedly examined the fossilized skull of a whale that lived 33 million years ago in what is today the state of Washington. The 4.7-meter-long whale, named Maiabalaena nesbittae, had emerged at a key time when some whales transitioned to filter feeding. When whales with this ability eat, their mouths work kind of like vacuum cleaners, and a mouth part called baleen is akin to the vacuum’s filter. But this fossil didn’t seem to have baleen, contrary to prevailing hypotheses about how filter feeding arose.

The appearance of baleen set the stage for the rise of the largest vertebrates ever known and a radiation in whale diversity. Baleen is made from keratin, the same material that forms hair, and is used as a food filter by the group of whales that includes blue whales, humpback whales, North Atlantic right whales, and bowhead whales.

“Baleen is one of the most complicated types of tissue that exist among mammals,” Peredo, a doctoral student studying paleobiology at George Mason University and the Smithsonian Institution, explains. “It must take a unique environmental context to cause such a radical change in a body plan.” Filter feeding only evolved this one time in mammals, and understanding how it arose could lead to many revelations about mammalian evolution. Peredo and his coauthors recently published a paper in Current Biology revealing M. nesbittae as a big piece to this puzzle.

Images from Peredo et al., Current Biology 28(23) 2018

Paleontologists knew that the common ancestors to baleen whales had teeth, so the questions are whether whales developed baleen before or after losing teeth and how they fed in the interim. There were several hypotheses about this transition, but most posited that baleen would be present in some form in the animals that appeared after their ancestral relatives with teeth and before those with only baleen.

After running anatomical tests and scrutinizing the cranial features, Peredo knew that M. nesbittae had no teeth. However, he was also seeing features that suggested that it didn’t have any baleen either. For example, the roof of the mouth was so thin that it seemed unlikely to be able to support baleen. That’s how Peredo began wondering whether it was crazy to think that this transitional whale lacked both teeth and baleen.

Upon hearing the idea, Peredo’s PhD co-advisor, paleontologist Mark D. Uhen of George Mason University, gave him a look and said, “This is my skeptical face.”

“He was right to be skeptical,” says Peredo. And that skepticism helped guide them to new evidence.

It turns out that some modern marine mammals suction-feed without teeth or baleen, swallowing prey without chewing or filtering. Narwhals, for example, technically have teeth—their tusks—but they don’t use them to chew. The Risso’s dolphin, sperm whales, and some beaked whales suction-feed without using teeth or baleen. “This isn’t so crazy,” Peredo says he realized as he studied these other species, and found that this feeding strategy evolved multiple times among marine mammals.

“Slowly over time, we built the evidence and started convincing people” about M. nesbittae, says Peredo, who plans to continue studying the whale’s contemporaries during the transition from the Eocene to the Oligocene epochs, about 34 million years ago. That transition was marked by changes in climate and ocean currents, and in turn, also in many marine organisms and their ecosystems.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.