This Article From Issue

November-December 2013

Volume 101, Number 6

Page 470

DOI: 10.1511/2013.105.470

THE MEASURE OF MANHATTAN: The Tumultuous Career and Surprising Legacy of John Randel Jr., Cartographer, Surveyor, Inventor. Marguerite Holloway. xii + 372 pp. W. W. Norton, 2013. $26.95 cloth, $16.95 paper.

John Randel Jr.’s farm maps of Manhattan Island look both gorgeous and absurd. As works of cartographic art, they are masterpieces: When the 92 sheets are fitted together, they are 50 feet long, forming the largest known map of Manhattan. The maps show the smallest elevation details, reflecting Randel’s painstaking survey work. They have lovely hill shading; property lines washed in soft blues, greens, yellows, and pinks; and planimetric views of houses and barns. The primary goal of the survey and maps was to describe a new grid outline for the city’s streets and avenues.

Settled on top of his detailed views of early 19th-century Manhattan (barns, streams, marshes, and hills), Randel’s envisioned Manhattan of the future seems like a joke. On the map, perfectly regular new streets and avenues run right over barns, hospitals, hills, and existing roads alike. At the western edge of the island, Twelfth Avenue cuts through bits of the Hudson River coastline, sometimes running into the water before emerging back on land. On the northeast end, Fifth and Sixth Avenues trail off into the water of the Harlem River, as if the idea of the grid is so ethereal that the roads themselves might just float. Of course, the real joke is that the future Randel’s maps propose has in fact come to be and has shaped the city for generations of New Yorkers.

Marguerite Holloway’s The Measure of Manhattan is the first major biography of Randel, a master cartographer whose long career included a wide range of innovations, frustrations, and lawsuits. The book intertwines his life story with a narrative about a group of present-day geographers and ecologists working to reconstruct the ecology of Manhattan Island as it existed before European settlement. Holloway’s fondness for digression bogs down parts of her story. However, the subplots and minor characters she introduces usefully highlight the failures, messiness, and complexity of surveying and geographic data. Largely because of this attention to detail, The Measure of Manhattan is a refreshing tour through the personal and professional realities of surveying in the early 19th century and today.

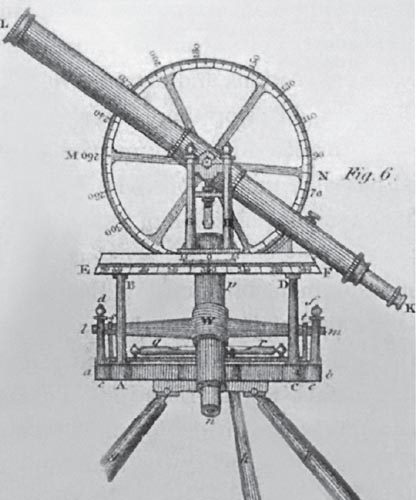

From The Measure of Manhattan.

In 1806 New York City’s Common Council embarked on a major project: surveying the public and private lands on the island of Manhattan and organizing them into an orderly grid. Randel got the job after the council’s first choice, Swiss-born surveyor Ferdinand Hassler, became ill. At the time, large parts of the island were still hilly, and the landscape was dotted with wetlands and marshes—not the easiest landscape to survey. In fact, previous surveys were riddled with inaccuracies. Randel was obsessed with precision, and to make his survey of Manhattan more accurate he spent between $2,400 and $3,000 of his own money (the equivalent of about $50,000 today) to have field instruments custom-made from his own designs. Devised to be more robust than other instruments available at the time, Randel’s custom equipment included an improved theodolite and several measuring rods, one of which was 50 feet long and designed like a suspension bridge.

Although he possessed great technical skill, Randel had a knack for making bad professional decisions. In 1817 he declined an offer to work as chief engineer on the eastern third of the Erie Canal. Realizing he might have missed an important career opportunity, he undertook a campaign on behalf of Albany city leaders, making the innovative argument that the canal should run through a four-mile underground tunnel, following the model of the Grand Union Canal in Northamptonshire, England. His ideas—first disseminated through anonymous letters signed “Friend of the Canal” and later through a self-published 72-page pamphlet—were largely ignored.

As we follow Randel’s canal digging (and later his visionary proposals for an elevated railway to extend down Broadway), Holloway does a marvelous job of conveying the man’s brilliance and zeal for accuracy. We also get the sense that he was creating a reputation for stubbornness, even litigation, that would alienate him from his colleagues and ultimately lead him to financial ruin.

Randel remains an important figure for surveyors and geographers. His work established the grid system for New York City streets, which has had a powerful influence on that city’s development. Trudging through the marshes with his workers as they carried stone markers from site to site, Randel literally imposed the grid on the landscape of Manhattan. As Holloway notes, the grid was not actually his idea. (One legend has it the Common Council came to the idea after seeing the shadow a sieve cast on top of a map of the island.) But Randel’s work may have helped bring the grid plan into reality, and landowners infuriated by it also used his map and survey to document what they would lose.

Today, the records Randel kept have been invaluable for the Welikia project, which reimagines the ecology and civilization of New York City as it might have been in 1609 before European settlement. In an era when geographic data is ever easier to access, The Measure of Manhattan reminds us of the intimate and difficult ongoing relationship between surveyors and the landscape they survey.

Tim Stallmann is a cartographer based in Durham, North Carolina. He is a member of 3Cs, the Counter-Cartographies Collective, a transnational collective of artists, scholars, and activists who work on mapping to render new images and practices of economies and social relations, destabilize centered and exclusionary representations of the social and economic, and construct new imaginaries of collective struggle and alternative worlds. His work focuses on using maps as tools to build community power, particularly around racial and economic justice.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.