This Article From Issue

July-August 2024

Volume 112, Number 4

Page 251

SCIENCE COMICS: ELEPHANTS: Living Large. Jason Viola; illustrated by Falynn Koch. 128 pp. First Second, 2024. $12.99.

Whether you love elephants or just want to learn more about these animals, this volume of the STEM graphic novel series Science Comics focusing on the world’s largest land mammals is one you won’t want to miss. Though the series is aimed toward middle-grade readers (those between the ages of 9 and 13), these books are packed with scientific information conveyed through a fun and engaging story, bringing facts to life and making science fun and visual.

Viola is a writer and cartoonist who writes biology comics (he’s also written the Science Comics volumes on polar bears and on the digestive system), and Koch is a writer and artist who’s written graphic novels on history and science (she’s written the Science Comics volumes on bats and on plagues). Together, they’ve created a book about an elephant named Duni who introduces readers to basics about elephants, how their communities are structured (did you know they’re matriarchal?), and the journey away from the family of origin that male elephants take at a certain age to join a unit of male elephants with whom they form a tight bond.

From Science Comics: Elephants: Living Large

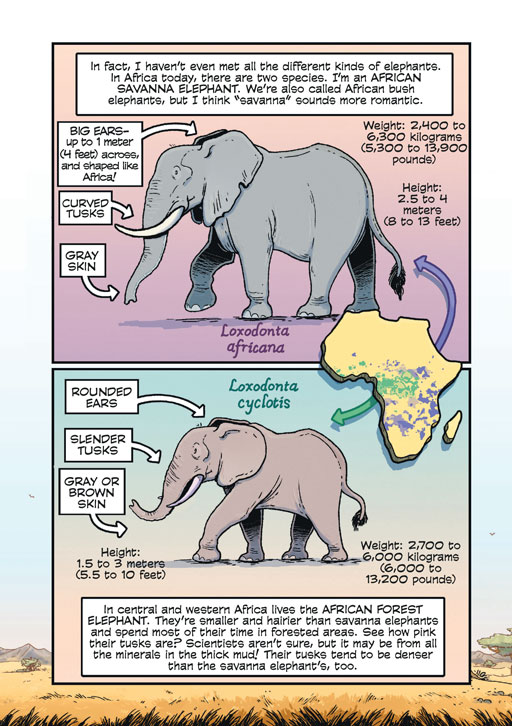

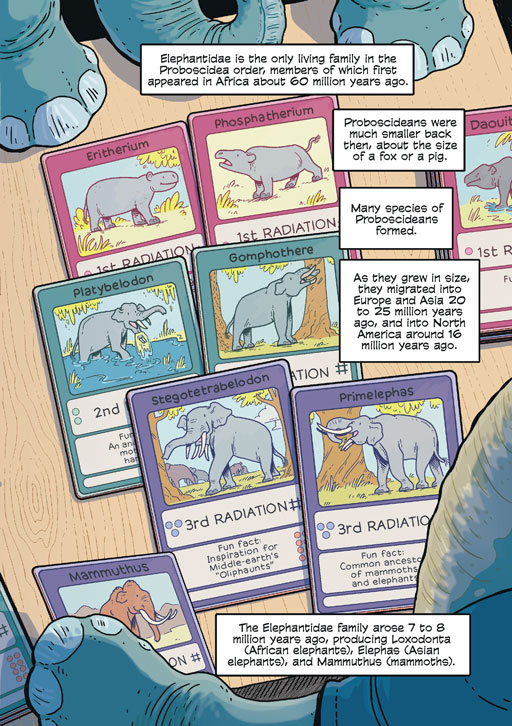

The excerpts pictured here show different kinds of elephants: the African savanna elephant and the African forest elephant on one page; on the other, the taxonomic order of the Proboscidea is shown, which has only one living family—Elephantidae.

But the story isn’t solely about Duni and his elephant community; the authors also touch on the effects that humans have had on the ecosystem of the elephants, as well as the danger they can pose to elephants themselves. Even with more serious topics, Viola and Koch present the information in a developmentally appropriate way that is integrated seamlessly into the larger narrative arc.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.