This Article From Issue

November-December 2024

Volume 112, Number 6

Page 333

Amid the dim light suffusing the subjects of Rembrandt van Rijn’s 1642 masterpiece The Night Watch, the central figure of Lieutenant Willem van Ruytenburch appears almost to glow, with his golden outfit cast in stark contrast to his companions’ somber tones. Rembrandt famously employed this artistic interplay of light and shadow, called chiaroscuro, in many of his works. Despite years of scholarship examining the combination of pigments used to create this luminous effect, however, the Dutch master’s palette still holds some surprises.

Chemist Fréderique T. H. Broers and conservator and researcher Nouchka De Keyser, both at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, have reexamined the sources of color in Rembrandt’s painting as part of Operation Night Watch, a large-scale conservation and research project. Their findings challenge assumptions about the types of pigments available in the mid-17th century and how they were used.

Rijksmuseum

At that time, a variety of red, yellow, and orange pigments were made from arsenic sulfide minerals obtained by mining: notably, the warm orange-yellow mineral orpiment (As2S3) and the bold red mineral realgar (As4S4). But artificial or synthetic arsenic sulfide pigments—broadly and misleadingly labeled “orpiments” by historical sources, regardless of their provenance or composition—could also be made through chemistry by heating, mixing, condensing, and purifying related elements and compounds; examples include heating a mixture of sulfur and the mineral arsenolite (As4O3, formed from the oxidation of arsenic sulfides), or directly combining elemental arsenic and sulfur. Historical documents investigated by the team show that Europeans were synthesizing artificial orpiments by the 15th century.

But some arsenic sulfide colorants can arise even after pigment has been applied to a canvas, because certain colorants degrade when exposed to light. Realgar, for example, breaks down into another pigment with the same chemical formula, called pararealgar. So how can researchers tell whether the evocative colors on a canvas come from an artist’s chosen pigment or its subsequent breakdown? De Keyser, Broers, and their team considered this question as they examined The Night Watch.

Like most great painters of his day, Rembrandt experimented with different methods and materials to achieve his desired effects on the canvas. But in the 17th century, the common yellow pigments were lead-tin yellow, yellow ochre, and yellow lake, and the widely used red pigments were vermilion, red ochres, and red lake. (Red and yellow lake pigments aren’t ground from minerals but rather made from dyes derived from plant or animal sources and precipitated on a chalk or potassium-based substrate.) Despite their eye-catching qualities, arsenic sulfide minerals were toxic, didn’t dry well, and were hard to work with. Moreover, suppliers would have had to import the pigments or their components from abroad because the Netherlands had no geological source of arsenic.

N. De Keyser, et al. 2024. Heritage Science 12:237, CC-BY-4.0

Only recently (in 2007 and 2017, respectively) have researchers found that Rembrandt used arsenic sulfides in two of his late-period paintings: The Man in a Red Cap (1660) and The Jewish Bride (1665–1669). Now it is clear the artist used arsenic sulfide pigments more than two decades earlier, too. “Nouchka and I were very excited, because we were researching arsenic sulfides before, and we weren’t really expecting them in The Night Watch,” Broers said.

Another surprise came as the team analyzed the form of the colorants, which can indicate if they are original pigments or degradation products.

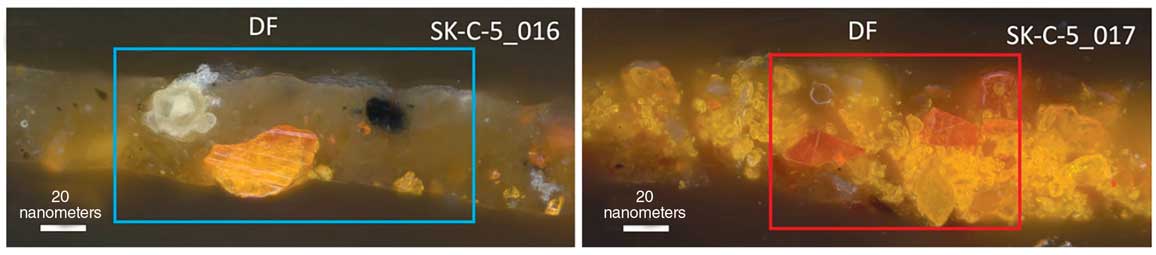

Prior studies that used light microscopes or elemental analysis of pigments in The Night Watch could not distinguish synthetic arsenic sulfides from their breakdown products. These analytical techniques also often failed to reveal the deeper deposits of paint, especially if the top layers contained heavy elements such as lead. So Broers, De Keyser, and their colleagues brought in more advanced tools. These included Raman spectroscopy, in which photons from a laser interact with a sample’s molecules. A graph representing the gain or loss of energy by photons from these interactions can reveal the structure, phase, and crystallinity of a sample.

Raman spectroscopy can thus distinguish realgar from pararealgar based on its different crystalline structure. What’s more, Raman analysis can distinguish pararealgar, which has a fully developed crystalline structure, from semi-amorphous pararealgar, which doesn’t. Finding this semi-amorphous variety is a key step in showing that humans had altered the pararealgar because this “glassy” state often occurs when materials are melted or sublimated and then quickly cooled. More significantly, it would indicate that the pigment was used in the painting as-is and did not result from the breakdown of realgar: Researchers have never found an instance of realgar degrading into semi-amorphous pararealgar.

The Rijksmuseum team also used x-ray powder diffraction. Exposing a powdered sample to a beam of x-rays, they measured how electrons in the sample’s atoms scattered the rays—and how the scattered beams interfered with one another, which depends strongly on the crystal planes and other properties of the sample. (See “Uncovering Ancient Corrections,” November–December 2023.)

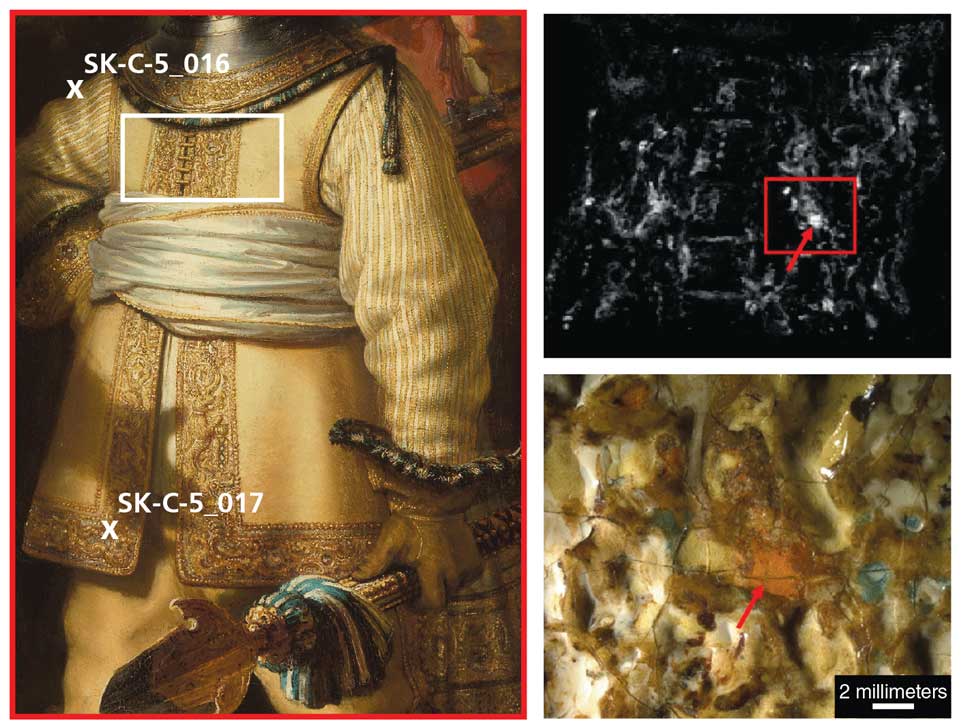

The process required removing some paint from The Night Watch, but researchers gathered their minuscule sample from a carefully chosen cross-section. “We want to have the stratigraphy—the layer buildup of the painting—so we take it quite as deep as possible to have a good sample,” De Keyser said. “But we take it in such a way that it’s barely seeable with the eye, so that we don’t obscure the paint layers.”

As they reported in the journal Heritage Science, Broers and De Keyser identified a mixture of yellow pararealgar and an orange-to-red semi-amorphous pararealgar in the depiction of van Ruytenburch’s coat. Significantly, they did not find any evidence that either of the two pararealgars had degraded from another pigment: The area studied contained no remnants of realgar, and the pararealgar samples were sharp-edged and situated in unaltered surroundings—the opposite of what would be expected had the colorant formed through degradation.

The use of pararealgar in European paintings and art objects remains a rare discovery. Yet the authors note that this does not mean that the pigment was not used more frequently or will not be found in more paintings as methodologies such as Raman spectroscopy advance and are used to study more paintings. Indeed, it wouldn’t be terribly surprising to find that Rembrandt and his contemporaries used pararealgar as a pigment—or as a starting material to make artificial versions of one. Realgar degrades quite quickly, which contemporaries must have known. Thus, the researchers argue that Rembrandt originally used pararealgar (for yellow) and semi-amorphous pararealgar (for orange to red) to achieve his desired golden effect. Adding credence to this conclusion is the fact that a contemporary artist based in Amsterdam, Willem Kalf (1619–1693), later used a similar mixture of pigments in his painting Still Life with a Silver Jug and a Porcelain Bowl (1655–1660). “This would suggest that [such pigments] could have been bought somewhere in Amsterdam,” Broers said.

Indeed, the authors also have reason to believe that Domenico Tintoretto’s Entry of Philip II into Mantua (1579 or 1580) might have used pararealgar as a pigment because previous analyses of that work by another team produced comparable results. If true, that would place the colorants in Venice, Italy, in the late 16th century.

The findings suggest that 17th-century Dutch artists had access to a greater range of arsenic sulfide pigments than previously thought and that they included pararealgar as a pigment, not merely as a by-product. The results also argue for revisiting old analyses of great artworks using the latest analytical techniques. Doing so could help experts better understand how chemically advanced pigment creation had become, how deeply such pigments penetrated European markets abroad, and how freely artists of the day experimented with pigments, even ones that were difficult or toxic to work with.

N. De Keyser, et al. 2024. Heritage Science 12:237, CC-BY-4.0

De Keyser will next evaluate the results from noninvasive imaging of The Night Watch to investigate the techniques Rembrandt used to achieve optical effects that no other painter has matched.

Meanwhile, Broers will turn her attention to a different pigment in the painting: smalt, a blue colorant made of powdered cobalt-oxide glass. Rembrandt used smalt extensively in his late paintings—mixing it with other pigments, taking advantage of its drying properties, and applying it to make his paint more translucent or to give it greater texture. However, the artist’s original intent was often clouded by later restorations, paint alterations, and his own experimentation, so there’s still much that experts don’t understand about his use of smalt.

“Rembrandt used it a lot,” Broers said. “And we’re looking at if, across the painting, he used different types of smalt, or if he sort of used it consistently.”

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.