This Article From Issue

March-April 2011

Volume 99, Number 2

Page 156

DOI: 10.1511/2011.89.156

WHAT TECHNOLOGY WANTS. Kevin Kelly. x + 406 pp. Viking, 2010. $27.95.

Whether it’s intended to be so or not, the title of Kevin Kelly’s What Technology Wants is a provocation to most historians of technology, who would reply almost unanimously that technology has no wants or desires. Each tool or machine has latent uses, but each is only an inert object until human beings decide whether and how to use it. In contrast, Kelly talks about technology as a composite whole that emerged before human beings existed and that facilitated their rapid domination of the planet. For him, technology has intentions, and it is radically accelerating evolution.

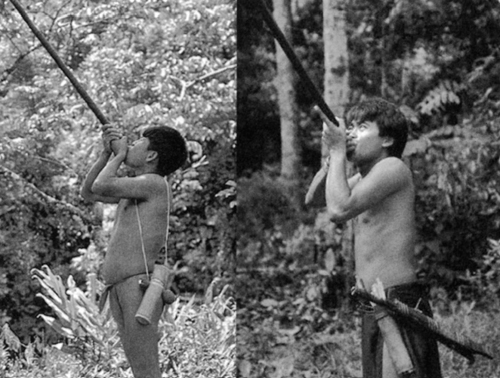

From What Technology Wants.

Kelly has been thinking about technology for most of his life, first as a backpacker wandering the Third World, later as one of the pioneers of what became the Internet, and finally as one of the founders and editors of Wired magazine. He overcame his early suspicion of Western technology largely as a result of his encounter with interactive computer technologies. He was one of several in the counterculture to move from working on the Whole Earth Catalog to celebrating the Internet as a new online facilitator of grassroots movements.

Kelly argues that all technologies, from the stone ax to the computer chip, should be seen as a collectivity—the technium, which is “the greater, global, massively interconnected system of technology vibrating around us” and includes “culture, art, social institutions, and intellectual creations of all types.” He coins the term because he wishes to emphasize the idea of technology as an overarching entity that constitutes the equivalent of an evolving “seventh kingdom of life,” one that “predated our humanness.” Indeed, the “root of the technium can be traced back to the life of an atom.” A bird’s nest and a wooden shack, a beaver’s dam and a dam built by engineers are all manipulations of natural materials to gain an environmental advantage. Rather than see technology as an expression of culture, Kelly argues that a garden, for instance, whether created by ants or human beings, is natural. Yet at the same time he sees technology as primarily being the projection of human ideas, in a process that accelerated suddenly 50,000 years ago when people acquired language. “The invention of language marks the last major transformation in the natural world and also the first transformation in the manufactured world,” says Kelly. It was manifested first in the conquest of the habitable world by Homo sapiens and second in the continual addition of new inventions. These in turn assured that material progress has kept accelerating. Moreover, Moore’s Law and its like suggest that technology obeys its own laws of development. Therefore, we must “listen to the technology” and learn where it is taking us.

Arguing for convergence and the inevitability of certain paths of development, Kelly draws an analogy with biology: “Again and again evolution returns to a few solutions that work.” He is convinced that natural selection is not based on random variation that might lead anywhere, but rather is directional, and he argues that technology also evolves along preordained paths. Technology can thus be said to “want” to develop in certain directions. He thinks the rough sequence of major inventions is largely invariant, and that such devices as the electric light bulb were inevitable, even if the specific details of their form were not. In support of this claim, Kelly points to the frequency of near-simultaneous invention of the same device and to parallels between technical developments in widely separated ancient societies. He seems to believe in something close to platonic forms: “Inventions and discoveries are crystals inherent in the technium, waiting to be manifested.”

Kelly claims that what technology wants is to keep evolving, in order to increase each of the following: efficiency, opportunity, emergence, complexity, diversity, specialization, ubiquity, freedom, mutualism, beauty, sentience, structure and evolvability. He does not see inherent contradictions in this list. Will more ubiquitous technologies increase beauty? Does increasing complexity produce greater efficiency? Do more structure and more specialization really ensure more freedom? Does more diversity enable more mutualism (whatever that term means)? Kelly’s list seems arbitrary. One might argue with equal plausibility that what technology wants is to eliminate or to dominate human beings and link up with “the technium” in the rest of the universe. Why assume it is benign?

Kelly sees progress, connections and inevitabilities where others would see problematic change, discontinuities and puzzles. If technological sequences are inevitable, then why did the Mayans, the Aztecs and the Incas all fail to develop the wheel? If technological progress is beneficent, then why have we developed so many poisons, computer viruses and weapons of mass destruction? If such progress is inevitable and accelerating, how to explain periods of stagnation or even backsliding, as when the Japanese briefly adopted the gun but then gave it up again for several centuries?

Kelly’s book is the latest example of the sort of argument once made by Marshall McLuhan, later favored in the writings of Alvin Toffler, and praised in the 1990s by Newt Gingrich. Those making such arguments seldom look closely at any particular technology, preferring to generalize about a wide range of tools, machines and practices. The almost invariable point is that technologies have an “inevitable” impact on a rather passive humanity, who need not worry because the trajectory of progress is assured. Such authors usually make many pronouncements, and Kelly is no exception—his include “technologies are forever,” “Homo sapiens is a tendency, not an entity,” and “the universe is mostly empty because it is waiting to be filled with the products of life and the technium.”

The notion that technology has its own agenda, forcing inevitable progress, is a dangerous one. If you believe it, then there is little need for—indeed, little point in—regulation or oversight. Either get out of the way or help technology do its thing. Or, alternatively, you can believe in this idea and therefore fear technology. Kelly devotes a chapter to the Unabomber and agrees with him, in part: “The Unabomber is right that technology is a holistic, self-perpetuating machine.” But Kelly argues that there is no need for a Luddite response, for the technium increases choice and fosters diversity more than it constrains freedom. Paradoxically, he also thinks that humanity is at a tipping point “where the technium’s ability to alter us exceeds our ability to alter the technium.” If the machinery is taking over, why should we expect our choices to expand?

For Kelly, not only is the glass half full, but also the invention of the glass was inevitable, the water is safe to drink, its level is rising, and it is part of an inevitable evolution toward more complex technologies to supply us with better fluids. Kelly seems to worry little about whether the glass may be half empty, the water may contain toxins, the mass production of glasses may pose a problem of waste, or our current consumption of water may be unsustainable. What Technology Wants is a book for people who believe, or want to believe, that technology is a coherent whole, that it grows out of nature and natural law, that it has its own trajectory, that it expresses a beneficent intentionality, that the sequence of its forms is inevitable, that the direction of its growth is predetermined and leads toward ever greater complexity and diversity, and that human beings have benefited and will continue to benefit as the technium accelerates. I am not convinced that any of these propositions are true, although Kelly does deserve credit for stitching together this synthesis that suggests the ideological links between the counterculture of the 1970s and the technoculture of Silicon Valley. I do not think there is any such thing as “the technium,” a woolly concept that is so capacious that it includes almost everything and therefore can define nothing. And even if I did believe that it existed, I would not argue that it “contains more goodness than anything else we know.” Nor do I agree that “we can see more of God in a cell phone than in a tree frog.” Most cell phones are on the scrap heap within two years of their manufacture, whereas tree frogs, which are disappearing at an alarming rate, survived millions of years before human beings began to wipe out species and destroy whole ecologies.

Kelly does acknowledge precisely this point early in the book:

Nothing we have made approaches the endurance of the least living thing. Many digital technologies have shorter life spans than individual mayflies, let alone species.

Likewise, he acknowledges global warming, nuclear weapons and other technological dangers, as though admitting their existence somehow neutralized them. I find myself thinking of the Beatles song “Getting Better”: Paul McCartney keeps insisting, “It’s getting better all the time,” but John Lennon interjects, “It can’t get no worse.” An argument for technological determinism could use a bit of that irony.

David E. Nye teaches at the University of Southern Denmark. He received the Leonardo da Vinci Prize in 2005 for his many books on technology and culture. His recent work includes Technology Matters (2006) and When the Lights Went Out (2010), both from The MIT Press.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.