This Article From Issue

January-February 2007

Volume 95, Number 1

Page 76

DOI: 10.1511/2007.63.76

The Making of the Fittest: DNA and the Ultimate Forensic Record of Evolution. Sean B. Carroll. 301 pp. W.W. Norton, 2006. $25.95.

Garry Trudeau recently composed a Doonesbury cartoon in which a doctor asks a patient with tuberculosis whether he is a creationist—saying that his answer will determine whether the treatment will be streptomycin (effective only for the TB of yesteryear) or a more modern antibiotic (one that would work on the drug-resistant strain into which the TB bacterium had lately evolved). Despite his religious convictions, the patient shows great interest in the updated drug. Sean Carroll, an evolutionary developmental biologist at the University of Wisconsin, opens his new book with a similar conundrum: Why is it that so many Americans are willing to use DNA to convict those accused of murder while simultaneously refusing to accept the validity of the overwhelming molecular evidence for evolution? Carroll has an interesting point, for many Americans harbor creationist sentiments yet seem quite happy to reap the fruits of modern research, such as nuclear power (or nuclear weapons!), the beneficial products of agricultural genetics, or forensic DNA, without acknowledging that the science underlying these advances has revealed an abundance of information (the radiometric dating of ancient rocks and the molecular fingerprints of evolution, for example) that is contrary to their fundamental beliefs.

Popular exposition about evolution has had difficulty conveying the incredible power of natural selection. The late Stephen Jay Gould perfected one approach, writing engaging essays about odd peculiarities whose only explanation can be evolution. Other approaches all too often get bogged down with such boring things as changing allele frequencies in peppered moths, and let's face it, no one, not even a population geneticist, has ever really enjoyed rehashing that argument.

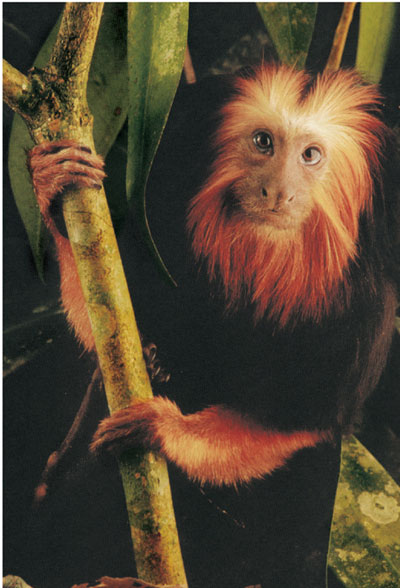

From The Making of the Fittest.

As a developmental biologist, Carroll has a far more engaging set of examples to offer: the remarkable genetic and developmental evidence for the evolution of antifreeze proteins in Antarctic fish, the evolution of color vision through the duplication of opsin genes in birds and primates, and the fossil evidence preserved in our own genes for battles against malaria. In each case, he describes both the basic natural history and the genetic changes involved.

Carroll does not shy away from the mathematics of natural selection, but he presents quantitative aspects of evolutionary theory in a deceptively simple manner (and yes, peppered moths make their obligatory appearance). He also includes some math in his discussion of Alberto Palleroni's investigation of falcon predation on pigeons near Davis, California, where, it turns out, a white rump on a pigeon evidently distracts falcons. Having conveyed the mathematical essence of such examples of natural selection, he can turn back to the compelling arguments that come from the work of his own lab and from the labs of many colleagues.

Of course, one wonders whether books like this ever reach their intended audience. Most readers of popular science books (and, presumably, most readers of American Scientist) recognize that there is not a scintilla of evidence for intelligent design or its more antiquated progenitor, creationism. (Indeed, these systems of belief are not just flawed, they are theologically bankrupt as well, as many theologians have pointed out.) Carroll is not, I think, so foolish as to think that his efforts will convert members of the Discovery Institute or the Institute for Creation Research. Rather, he aims at the middle ground: those sufficiently curious about the world and how it works to want to understand, rather than to rely on blind faith. In this he is, I think, quite successful.

Carroll does not shrink from confronting head-on the intellectual poverty and often downright dishonesty of the purveyors of "creationist science." In a chapter on creationists, he begins with a review of Lysenkoism and the damage it did for several decades to genetics (and to science in general) in the Soviet Union. Chiropractors and their battles against immunization then serve as a cautionary tale, demonstrating that such anti-scientific posturing is not limited to other countries. Carroll then identifies in the behavior of creationists several of the techniques of disinformation characteristic of these two movements. It should go without saying, but sadly cannot, that Carroll's complaint is not with religion as such, but with those fundamentalists whose fear of intellectual inquiry leads them to such discreditable ends.

I do wish that Carroll had shared more of his views about the future directions of evolutionary theory, a topic he touched on near the end of his previous book, Endless Forms Most Beautiful. He is among those who feel that science is on the verge of a new synthesis in evolutionary biology (a perspective I share). Yet he missed an opportunity here to elaborate on what the future might bring and to show how scientists deal with new data that challenge received wisdom.

Carroll is a devoted father, and his children make frequent appearances during the course of family trips to satiate Dad's love of natural history. As a field geologist, I get a sense that part of Carroll wishes he had become a field biologist, tracking snakes through the underbrush. But we are all fortunate that instead he has become a vital contributor to the growth of evolutionary developmental biology and is now an engaging author of popular books on this and allied subjects. Conveying the excitement of current research while also providing a firm foundation of why we know what we know is a rare gift. In The Making of the Fittest, Carroll offers a graceful and insightful view of the explanatory power of evolution.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.