First Person: Manuel Lima

By Fenella Saunders

The Human Need for Visible Data

The Human Need for Visible Data

Few people can look at a set of raw data and see patterns. We are visual creatures, and data have to be interpreted for us to make sense of them. How best to do that is the expertise of Manuel Lima, Senior UX Design Leader for Google and Product, UX, and Data Visualization Mentor for the first class of Google for Startups Accelerator on the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals. Lima has a background in design, but he digs deep into cognitive science and human behavior to determine how best to inform design. He previously developed a comprehensive database at visualcomplexity.com to explore themes across projects and to tease out the building blocks of a good visualization. He’s also an avid historian, and the author of three books, exploring how certain visual themes, such as circles, go back to the beginnings of human understanding. Here he discusses how science and data visualization go hand-in-hand to produce new insights, discoveries, and impacts on society. He spoke to editor-in-chief Fenella Saunders about his views on complexity, patterns, and design.

Photo courtesy of Manuel Lima.

The term data visualization is a relatively recent buzzword, but the connection between visualization and data has been around for centuries. Why has the concept become so prevalent recently?

My interest in historical data visualization stems from my obsession with the origin of things. Who were the first people to create a chart, to create a graphic, to worry about the things so many of us are worried about today?

Most books on data visualization start with the 18th century, what they call the “golden age” of information graphics. That is when people like William Playfair, Joseph Priestley, and a bunch of other key figures in the field created the first information graphics. But for me that always felt a bit superficial, in the sense that—you’re telling me that nothing existed before the 18th century? I would beg to differ.

My most recent book [The Book of Circles: Visualizing Spheres of Knowledge] was an attempt to go as far back as I could when it comes to diagrammatic representation. It took me back roughly 40,000 years, to the very first rock carvings, or petroglyphs, and some of the visual metaphors and symbols that early humans created.

And then you see the High Middle Ages [1000 to 1250 CE], which I think was really the genesis of information design today, in the sense that Europeans were feeling very similar to us today. They were overwhelmed with new information coming from ancient Rome and ancient Greece, and they had to make sense of it. They experimented with a bunch of different visual metaphors. There were very prolific people doing wild work. Some of them wanted to replace text altogether. Get rid of text, we only need images from now on. They were as radical as that.

“The great part of visualization is the power to make the invisible visible.”

But then there was the golden age, which I call the “second period,” and now the modern age, the birth of this buzzword. There are multiple factors behind the renewed interest in data visualization. There’s the growth in storage. Our ability to generate data has by far outpaced our ability to make sense of it. That alone has triggered innovation in data visualization and tools such as AI, to help us make sense of this massive amount of data. There has also been a huge democratization of the tools. We now have dozens of tools that make it easy for anyone to work in this area. There was also a democratization of data, open data. Data became a commodity. Anyone can use data.

Those are some of the factors you see at play as far as why data visualization is becoming such a buzzword. But it’s also important to show the context, to provide the history. It’s not completely new. We’ve been doing this for centuries now.

Why do we need data visualizations?

The great part of visualization—even more powerful than text or numbers themselves―is the power to make the invisible visible. No matter how much you can describe something in text, there’s nothing like seeing an image or representation of it to make better sense of it. Humans were using visual communication way before they had any written alphabet, the oldest known of which is roughly 6,000 years old. We have, inherently, a huge aptitude and appetite for the visual. We should leverage that. I see data visualization as another tool for explanation, for adding clarity to your point, for making something visible and more understandable.

What are some of the ethical concerns behind data visualization?

Every once in a while you have what I would call the “data purists,” who say you’re destroying the data, because you should let the data speak on its own, and not convey it visually, because you’re just biasing the data altogether.

Of course that’s a lot of gibberish to me, if only because raw data is meaningless to humans. There’s no way you can make any meaningful patterns through data alone. There’s always an aspect of data transformation that’s required for us humans to interpret and make sense of it. As part of that transformation, there’s also space for biases to trickle in, as with everything.

There are three stages when it comes to grabbing the data and visualizing it. First you have data collection. Even the choice to go out and pick a specific data set is a form of bias. You’re making a selection. You could have chosen a different one.

Then data analysis is an important part of the process where biases can trickle in. You can easily remove columns and aspects of the data that are not interesting or relevant to your hypothesis, and you can add others. There are a lot of playful things you can do with data behind the scenes.

And then the final stage is visual encoding. There are the building blocks, in this case graphics, that can change in terms of shapes, colors, and sizes. Then there’s the grammar of graphics, the rules of how to combine them in ways that are effective. It’s important that the person creating the visualization understands basic design principles, especially those that come from cognitive science.

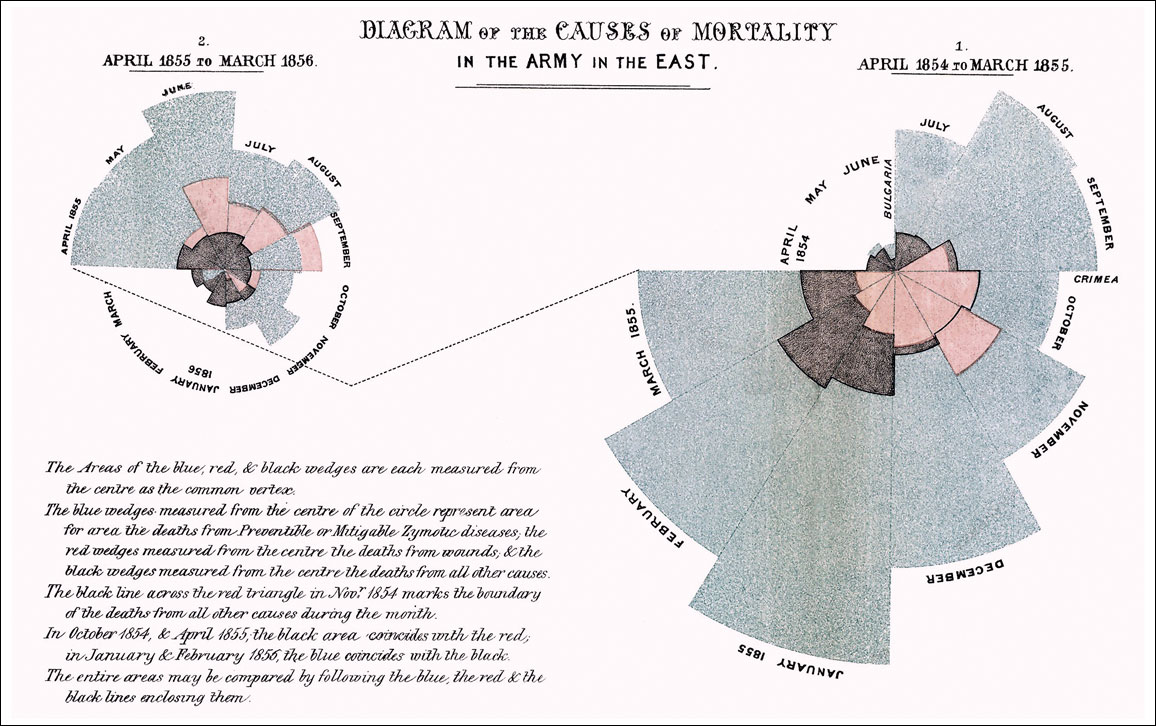

Wikimedia Commons

The notion of ethics in data visualization is central to the future of the practice. Transparency is a big part of it, being open about what data you’re using. Linking to the data, explaining how the data was treated, the data transformation part, those are good things. But I think it’s really upon us to always take things with a bit of a grain of salt. For example, in the early days of the COVID-19 outbreak, there was a viral tweet of a graph saying that South Korea was a hot spot. But at that time, South Korea was testing 10,000 people a day, versus the United States, which was testing maybe 20 people a day then. The way the data were being collected dramatically changed the way the graphic was perceived. Data availability is one aspect that influences the final outcome of the visualization.

Where is the line between complexity and clarity in creating beautiful graphics?

There is a misperception that aesthetics live on the other end of the spectrum from clarity, which is not true.

There’s this amazing principle called the aesthetic usability effect. It basically says that people perceive beautiful objects to be easier to use than less beautiful objects, even if they’re not. People are also more forgiving of a beautiful product than a less beautiful product. So aesthetics can have a critical role in usability.

And when the lack of clarity exists, I don’t think it’s necessarily the fault of aesthetics or beauty. We can’t avoid complexity altogether. But there are different approaches and techniques to solve complexity. For example, one method that dates back to the High Middle Ages is chunking. That’s why, today, we have credit cards with four strings of four numbers each. It’s easier to memorize than a full string of 16 digits. That’s an attempt to minimize complexity.

Another method in interaction design is progressive disclosure. Let’s say you’re visualizing a network. Instead of introducing the entire system at once, you introduce the user to nuggets at a time, and you slowly, progressively disclose more and more information. The best examples are digital maps. As you zoom out, you see the entire world. At some point there are no boundaries between countries, only continents. As you zoom in, you see countries. Then you start seeing highways. You progressively disclose more and more information. You would never show it all at once, because it would be nonsensical. Those are some of the approaches designers can take to minimize complexity.

What is the barrier that prevents more artists and scientists from connecting?

Design has been categorized as an art discipline, but that’s an artifact from the past. I’d suggest that one way to close that gap is to have design be part of an engineering school. A few schools do that, but not many. Then designers and engineers will start having that collaboration be more effective. In most cases, that’s the collaboration they’re going to have when they go and find a real job.

What are some examples of visualizations that brought about change?

One example is Florence Nightingale [1820–1910]. She did a beautiful visual representation of deaths in the Crimean War. She was blown away by how many soldiers were dying, not necessarily from wounds inflicted in battle, but from poor hygiene and sanitary conditions in the hospitals. She created a chart that was sent to the government in the U.K., and it led to huge changes in policy. They started improving conditions in hospitals, and that led to her being known as a key precursor to modern-day nursing. Her contribution was remarkable.

The first edition of On the Origin of Species has one single illustration. There’s a letter from Darwin to the publisher saying that it was critical that this illustration went into the book. It was critical to his theory, to explain how his ideas on evolution worked. This illustration was called the Tree of Life, and it was immensely powerful. A lot of the understanding of the theory of evolution came through this illustration alone.

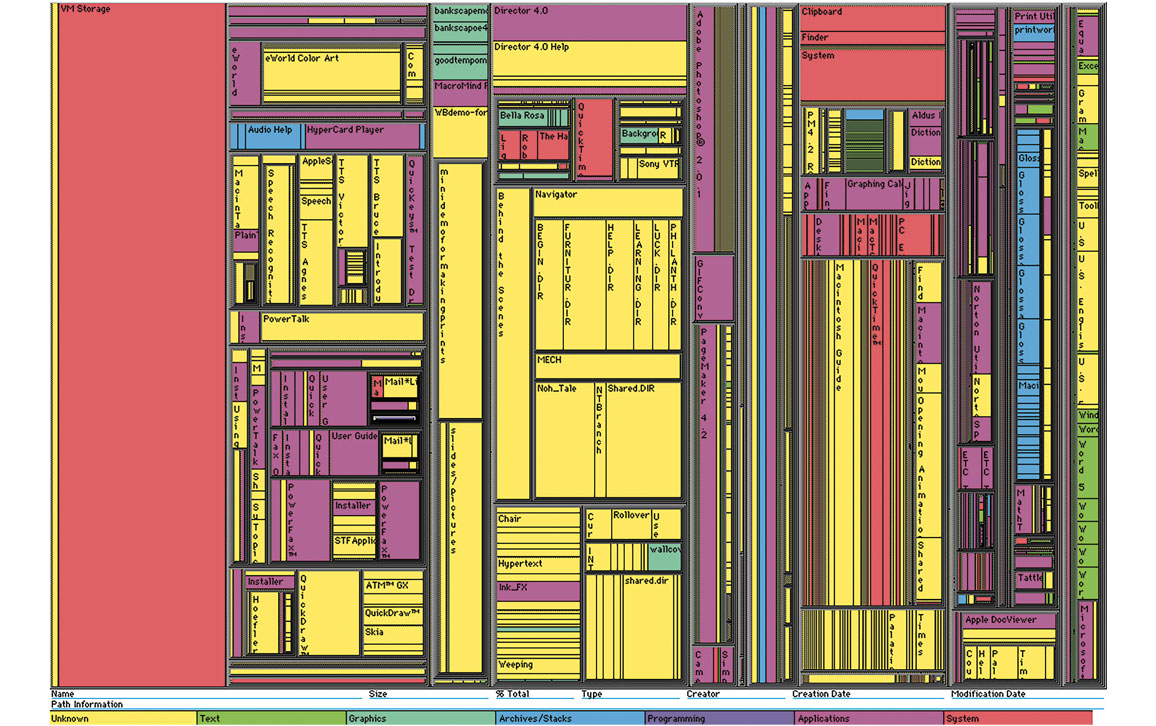

Courtesy of the University of Maryland

In a more modern example, you’ve probably seen visuals that claim, “This is the map of the internet,” and I always take that with a grain of salt. Of course it’s not. It’s one map of the internet. There are countless others you could make that are equally relevant. But it’s finding that right angle, the right perspective from which to visualize and understand something, that’s what makes it powerful.

Do you think visualizations have value as art, as well as scientific value?

There’s a huge cross-pollination today between art and science, specifically in the field of data science, data visualization, and data art. Artists today, even those from traditional fields such as painting and sculpture, are affected by everything else that’s going on in the world, as they always have been. They’re even sometimes the first to notice patterns. Data sets are just new ingredients for them to play with.

I was more critical in the past when graphics were not always effective. I think we need to have space for exploration. We’ve been using and repurposing old visual metaphors for too long. We’re facing challenges of a whole different nature. We need people to explore new ways of visualizing things, because that’s the only way we’re going to be able to come up with really novel models for visualization. We need to experiment. With experimentation comes failure. That’s part of it. Many times you will fail. But we need to invest and provide space to innovate.

A podcast based on an audio interview with Manuel Lima:

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.