This Article From Issue

July-August 2020

Volume 108, Number 4

Page 208

Cognitive scientist Anina Rich came to study synesthesia, the phenomenon of responding in an unusual way to a sensory stimulus, through a serendipitous fusion of interests. While in graduate school studying how the brain pays attention to visual cues, Rich helped a journalist who was writing about synesthesia. A note at the end of the subsequent article invited readers to get in touch with Rich if they’d ever had a synesthetic experience. At the time, the condition was thought to affect just one person in 25,000, “but within a week, I had more than 100 letters from people saying, ‘I do this! I didn’t know anyone else did,’” Rich recalls. Today, she heads the Perception in Action Research Centre at Macquarie University in Australia and the Synaesthesia at Macquarie research group, where she investigates synesthesia to learn about how the brain integrates information. Rich spoke with special issue editor Corey S. Powell about her research.

Photography courtesy of Anina Rich.

People often use the term synesthesia to describe any kind of cross-connection between the senses. How do you define it scientifically?

I typically define synesthesia as an extraordinary response or experience to a very ordinary stimulus.

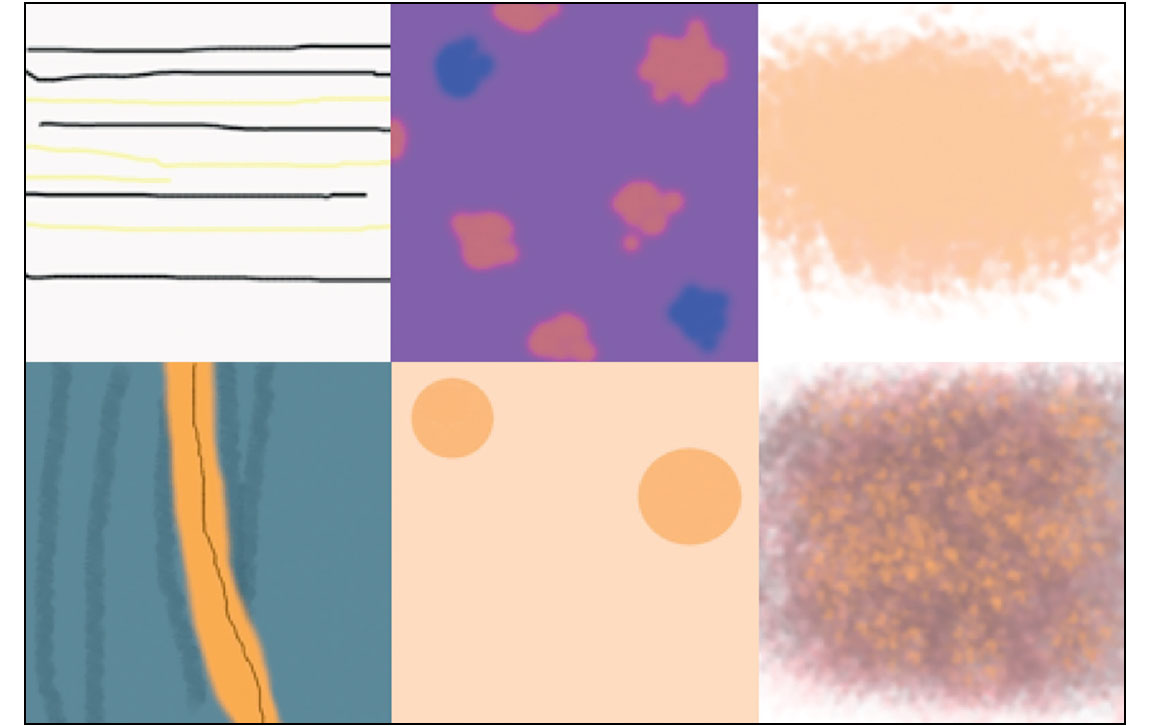

For most of us, a sound is an auditory event. We process that sound and we assign it meaning. “That’s the sound of my dog playing with his bone,” and so on. For a synesthete, they have that auditory event, but they have an extraordinary experience associated with it. For auditory-visual synesthetes, that sound would have all of those auditory associations plus a visual component. The sound of my dog playing with his bone may evoke a particular visual pattern, or a color. We showed that it’s not just a color in auditory-visual synesthesia; it also tends to have a form and a particular location in space. For grapheme-color synesthetes—for whom letters, numbers, and words evoke a color experience—again, it’s an ordinary stimulus, a letter, and then there’s an extraordinary experience associated with it, meaning it does not happening for most people.

You describe synesthesia as an added experience. Does it ever interfere with other experiences, or lead to conflicts with the regular sensory responses?

There’s no strong evidence that I’m aware of that synesthesia prevents or interferes with the basic sensory processes. My working hypothesis, based on the data, is that synesthesia is at a more conceptual level.

There had been a perception that synesthesia must be due to very low-level, hardwired connections between, say, audition and vision, or vision processing in the word form area and the color area of the brain. But the body of evidence suggests that it’s at a far higher level. And so if there was anything where synesthesia directly interfered with sensory input, I’d be very surprised.

That’s not to say that you can’t see the effect of synesthesia on something else. It’s just that these effects tend to be at a higher level. And by that I mean, for example, the synesthetic congruency effect that we’ve used as an index of synesthesia. If you set up a situation where you have a letter that’s in color, and the task is simply to name the color on a computer screen as quickly as possible, everyone can do this. You see a blue A, you say “blue.” For synesthetes, a blue A might be incongruent with their synesthetic color elicited by the A. About 40 percent of synesthetes—more than you’d expect—say that A is some shade of red, so if you show them a blue A, they try to say “blue,” but the A is giving them red. And what you see in that situation is that synesthetes are slower than control subjects for whom it makes no difference.

Does your synesthesia research suggest a more holistic way to think about sensory processing in the brain?

Typically in cognitive neuroscience, we study each of the senses separately, because it’s a bit more manageable. But, of course, in the brain our conscious experience is not separate. Synesthesia offers a unique insight into putting information together across the senses.

Synesthesia emphasizes the idea that perception is not just an interpretation of what’s there in the world; it’s an interpretation based on your preexisting knowledge. This framework is not just about incoming sensory information, but that integration with what you already know, or expect, or predict.

There’s a lot of work in many different, intermingled fields on the ways in which we perceive the world. Some work suggests that the brain predicts what’s going to happen, and then the brain calculates an error signal between this prediction and the incoming input. How the feedback from higher-level, more complex processing in the brain comes down to sensory cortices is an important area of research. I see synesthesia as a window into those types of processes.

Synesthesia researchers fall into two broad categories. One is people who study synesthesia because it’s fascinating and intriguing, and they want to understand the phenomenon. Their whole labs might be around synesthesia. And then other people, and I would count myself in this group, see it as a way of answering more general questions about cognition. It’s intriguing that a small proportion of the population have these additional experiences that the rest of us can never share.

If you ask people whether they associate colors with numbers, many people say “yes.” How do you define the boundary between such common, cross-sensory experiences and true synesthesia?

There are researchers who say that synesthesia is categorical—that there is something very different in synesthetes’ brains compared to non-synesthetes—and then there are those of us who think it’s on a continuum. At the other end from synesthetes might be people with aphantasia, who have no mental imagery whatsoever. And in the middle you have some of those societal examples.

For example, if you ask people to associate colors with letters of the alphabet, 60 percent of controls say that A is associated with red if you make them choose. Many of the things that synesthetes experience are also seen in non-synesthetes who are asked to do this nonsensical task of associating letters with colors. It’s not so easy to say, “This person is a synesthete and this person is not.” But there’s clearly a difference between saying “A could be red” and “A is a specific dark maroon with a little bit of black around the edge.” Part of it is the specificity of the experiences.

In the field, people use consistency as a measure because when we’re recruiting subjects, if their synesthesia isn’t consistent, it’s very hard to study it. Having said that, there’s probably a bias in what we’re studying now. I don’t think consistency is a gold standard for defining if you’re a synesthete or not. But unfortunately, scientifically it has become definitive because it’s a way of distinguishing people who I can study from those I can’t.

To the extent that you can broadly separate synesthetes from non-synesthetes, do you see any features that are unique to the synesthetic brain?

There’s no convincing evidence that there are marked differences in the brains of synesthetes and non-synesthetes structurally. There’s one or two studies that hint they maybe have stronger connectivity in certain areas, but those have also been challenged on methodological grounds.

My general take is that synesthetes don’t have different brains, but they might be using them slightly differently. Neurons that fire together wire together. If you have two things that respond at the same time enough, then you’ll get a stronger connection than two things that typically don’t fire together. It makes sense that there might be some connections that are stronger in synesthetes than in non-synesthetes. They probably don’t have vastly different connections from the rest of us, but perhaps those connections are stronger, or there’s some aspect of it that raises their firing above a threshold. Clearly there is something about synesthetes that results in them having a conscious experience that the rest of us don’t have. But there’s growing evidence suggesting that it builds on mechanisms that we all do have.

It could be that synesthetes are hyper-associators. We’ve all evolved to associate information. When a baby is born, they try to link the sound of a voice, or the look of a face. We’re constantly making associations. Maybe synesthetes have greater capacity for strong associations.

Do synesthetes ever consider their ability a burden or a source of confusion?

I’ve probably corresponded with well over 1,000 synesthetes, and of those I can think of three who said “If you ever find a way of getting rid of it, I want to know.” One man had bidirectional synesthesia, which is very unusual. Sounds gave him color but also color gave him sound, and he could get a headache from sitting in a room with dark red curtains because he would get this high-pitched sound.

I’ve also had a handful of people who can describe really specific instances where synesthesia caused problems for them. A teenager who was learning to drive said, “My right hand is one color, and my left hand is another color, but the words right and left are the opposite. So when the driving instructor says, ‘Turn right,’ I don’t know which way that is.”

Image adapted from A. Russell et al., Cognitive Neuroscience 6:77.

What about the converse: Can synesthesia be a source of creative inspiration?

Many people find ways to use it creatively. Musicians, for example. I remember one of my synesthetes saying, “When I’m improvising, I know what the colors should be. It’s an F, so I just play yellow.” Lots of artists do seem to use it in a much more conscious way. Carol Steen is an artist in New York. She actively has used her synesthesia for many years. It’s interesting, because her recent art has changed quite a lot, and she was describing to me that it’s still synesthesia, but it’s quite a different facet of it that she hadn’t explored before.

People use it creatively. But for most people, it’s just how they do things. They don’t get what’s different about it. One of my synesthetes described it really well. She said, “It’s like you’re seeing your own nose.” I can see my nose, but I don’t go around seeing my nose all the time. It’s just there.

Synesthesia reminds us of the inherent subjectivity of perception in us all. I can never verify that what I see or hear is the same in my experience as it is in yours. We’re not seeing what’s out there. We’re seeing what’s inside ourselves.

A podcast based on an audio interview with Anina Rich:

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.