This Article From Issue

March-April 2017

Volume 105, Number 2

Page 120

AN ADVENTURE IN STATISTICS: The Reality Enigma. Andy Field. Illustrated by James Iles. 746 pp. SAGE Publications, 2016. $56.

In graduate school, I searched and searched for a good applied statistics textbook—one that not only explained analyses and how they work but also covered how to prepare and check one’s data, write the programming code, and read the output. Like most ecologists, I needed to learn a vast array of analytical techniques. I ended up cobbling together what I needed using several books. A Primer for Ecological Statistics, by Nicholas J. Gotelli and Aaron M. Ellison, was fine for checking the basics. For multivariate analyses, I referred to Analysis of Ecological Communities, by Bruce McCune and James B. Grace, and Using Multivariate Statistics, by Barbara G. Tabachnick and Linda S. Fidell. Over the course of those doctoral research years, as well as when I began teaching undergraduate biology, I picked up a variety of statistics textbooks and put most of them right back down.

Further complicating matters, researchers who rely on statistical analysis of their data must typically be familiar with some sort of programming code to run the numbers. Mastering how to write the code and interpret the output can be big hurdles for early-career scientists—especially as the number of analyses they may need to have in their toolboxes has proliferated. During my last year of dissertation research, I read about the code language for the free program R using Michael J. Crawley’sThe R Book. This freeware had vast online help networks that enabled me to find what I needed fairly quickly and cheaply; it made much nicer visual graphics than SAS software did; and it offered me the ability to do analyses that other statistical software packages couldn’t easily perform.

Now, many years later, I have at last encountered a book that provides solid, innovative statistics instruction alongside lessons in coding. And it’s fair to say that it does so like no other. Andy Field’s An Adventure in Statistics: The Reality Enigma—an introductory statistics educational text embedded in a science fiction story with graphic-novel artwork—has caught my attention and kept it. If only I’d had this book back in grad school.

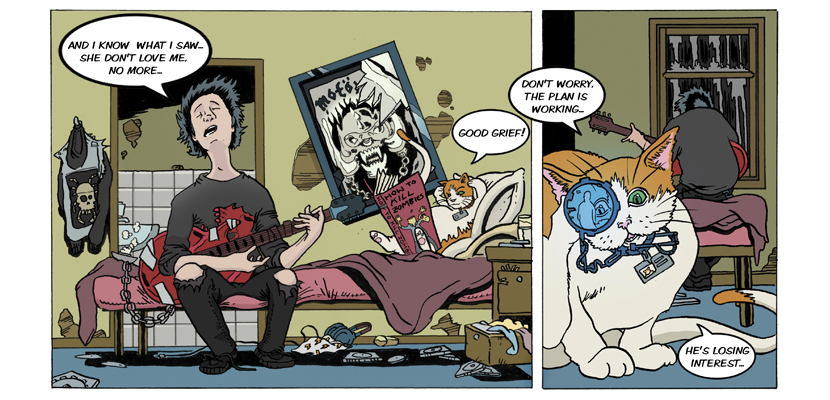

From An Adventure in Statistics. Illustration by Andy Field, © 2016. Courtesy of SAGE Publishing.

Field, a professor of child psychopathology at the University of Sussex, is the author of the popular textbook Discovering Statistics Using SPSS [Statistical Package for the Social Sciences], which has gone through three editions, selling hundreds of thousands of copies. When Field asked his publisher, SAGE Publications, for permission to write a “statistics for dummies” book as part of a series put out by a rival publisher, he was told that if he would write the book for SAGE instead, he would be given complete authorial control— freedom to do whatever he wanted. An Adventure in Statistics was the result. Field has created (if you’ll forgive the pun) a truly novel textbook: one driven by a fictional plot, full of quirky science fiction tropes, in which readers accompany the protagonist on a quest to learn statistics. Like a standard textbook, it is organized into a logical sequence of instructional chapters, with review questions and activities at the end of each. But unlike most textbooks, the fictional plot guides the reader throughout and is accompanied by comic-book–style illustrations. Field also freely blends elements from the thriller and horror genres into the tale as his protagonist races to locate a missing person and faces a zombie apocalypse. The book is unlike anything else out there, but it works despite—or maybe because of—its peculiarity.

Field uses the book’s prologue to set the scene, introducing readers to a dystopian future in which the invention of a “reality prism” has made it possible for anyone wearing the device to see truth objectively and to separate out subjective experience. This invention, developed a few decades before the story’s action begins, has brought about a revolution through the demise of not only propaganda and media spin but also religion, art, music, creativity, and people’s sense of purpose. When a new World Governance Agency embeds in its citizens Wi-Fi–enabled microchips that record what a person sees, thinks, and hears in real time, a schism emerges: On one side are those who accept the chips in order to join a virtual hive mind; on the other are those who refuse them, preferring instead a steampunk-like love of anachronism. In Field’s hands, the reality prism serves as more than an interesting premise. He uses the invention to cheekily make points about the difficulty of defining objectivity, adding depth and dimension to a question at the root of the practice of statistics.

Taking this destabilized world as its backdrop, Field’s tale centers on two characters who have been romantic partners for 10 years and share an apartment: Zach, the lead singer in a metal band called The Reality Enigma, who follows his gut feelings, and Alice, a scientist who bases her decisions on evidence. Zach is in awe of Alice’s scientific prowess, although he doesn’t always understand her work. When Alice disappears, with all records of her existence having been erased, Zach decides that in order to understand her research and why she might have disappeared, he has to learn science and statistics—even though he hates math and admits that it made him feel “inferior and frustrated” in school. His quest brings him into contact with a passel of wacky characters, including Milton—a talking ginger cat that keeps texting him statistics hints and is, incidentally, a scientist trapped in a cat’s body—and Celia, a beautiful fan of his music who has a big crush on him and who also happens to work at a mysterious scientific research institution, JIG:SAW, which was mentioned multiple times in the data files that Alice left behind on the day she disappeared.

As Zach progresses through his quest, he receives a comprehensive introduction to statistics. Like many introductory statistics texts, this one starts with basic ideas about sampling designs and the distribution of data, and it ends with a common method for comparing two or more means—analysis of variance, including factorial and repeated-measures designs. The text does not give a comprehensive overview of nonlinear or multivariate models. It covers the basics, however, and provides guidelines for avoiding pitfalls commonly encountered by novice researchers, both of which it does considerably better than many other textbooks I’ve examined. Each chapter ends with a set of activities and questions (labeled “puzzles”) that help the reader review the concepts covered. Unlike the standard textbook examples and exercises, however, these consider topics such as zombie rehabilitation, the psychology of cheating on one’s partner, and the business of successfully promoting a metal band with merchandise.

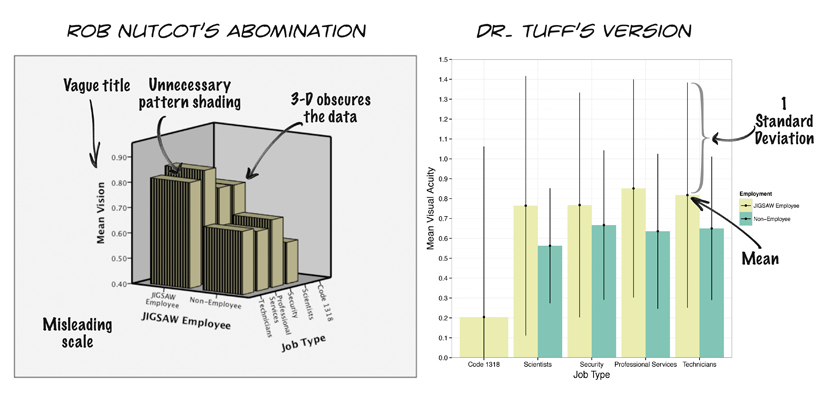

In addition, data files and R scripts for some of the problems are available. I like that Field offers these, as well as an ample number of images that show effective data visualizations. The examples of code and output in R for particular analyses are an essential part of an applied statistics textbook if one is using it to teach oneself and is applying the lessons to one’s own data. Readers can also find videos of lectures by Field on his YouTube page (http://bit.ly/2kWEhfv), along with tutorials for both his earlier statistics textbook and this one.

Field’s clear and fun explanations demonstrate that he is an experienced and conscientious teacher. Through Zach’s first-person narration, Field shows that the protagonist’s biggest hindrance is his own insecurity about math, not any inability to do statistics and understand it. And Field gives Zach—and readers—reassurance when the topic is especially difficult. For example, when Milton explains degrees of freedom, Zach responds, “That made no sense whatsoever.” Milton answers, “Worry not: Nobody understands degrees of freedom.” Presenting statistics instruction in a narrative format enables Field to create an emotional connection with readers that typical textbooks, and many teachers, do not.

As an experienced educator, Field has a good sense of where a student might get held up, and he makes sure to cover such topics repeatedly to emphasize certain points. But he maintains a teacher’s sense of humor about students and their tendency not to listen well to their instructor. At one point, Zach gets confused about why a technique for repelling zombies doesn’t work, even though data supporting the technique are available. He asks Milton, “Why would you have a model that fits well but doesn’t turn out to be much use in the real world?” Field’s description of Milton’s reaction to this remark depicts teacherly exasperation: “Milton’s face contorted into a strange mix of admiration and suicidal ideation. ‘I spent a great deal of time telling you about sources of bias that can influence the linear model. Must you subject me to the utter tedium of explaining all of that again?’” Then Milton proceeds to give Zach a quick overview of the main points already made about bias. Field clearly wants to emphasize the importance of understanding bias in linear-model statistics, but he also seizes the opportunity to playfully tease those readers in need of a recap.

As an experienced educator, Field has a good sense of where a student might get held up, and he makes sure to cover such topics repeatedly to emphasize certain points. But he maintains a teacher’s sense of humor about students and their tendency not to listen well to their instructor. At one point, Zach gets confused about why a technique for repelling zombies doesn’t work, even though data supporting the technique are available. He asks Milton, “Why would you have a model that fits well but doesn’t turn out to be much use in the real world?” Field’s description of Milton’s reaction to this remark depicts teacherly exasperation: “Milton’s face contorted into a strange mix of admiration and suicidal ideation. ‘I spent a great deal of time telling you about sources of bias that can influence the linear model. Must you subject me to the utter tedium of explaining all of that again?’” Then Milton proceeds to give Zach a quick overview of the main points already made about bias. Field clearly wants to emphasize the importance of understanding bias in linear-model statistics, but he also seizes the opportunity to playfully tease those readers in need of a recap.

From An Adventure in Statistics. Illustration by Andy Field, © 2016. Courtesy of SAGE.

This failure to repel zombies is not the only occasion on which statistics obscure the truth. All the characters struggle to trust one another, and many discover others to be “lying” with statistics—through poor choice of analysis, failure of the data to conform to assumptions, misapprehension of the data’s structure or outliers, or the creation of misleading data visualizations. In this way, Field teaches that statistics is a tool that can be used not just to solve problems and comprehend complex patterns, but also to deceive—or to confirm biases. Often this subject is not addressed so overtly in statistics classes, especially in cases in which it might court controversy or complicate homework assignments. The fictionalized data avoid these downsides while communicating important cautionary notes.

Milton ends up being Zach’s de facto statistics teacher for most of the book. He is incredibly hard on Zach in an ironic, catty way, but when Zach loses confidence or when others attack his knowledge of statistics, Milton has his back. Most of the time, Milton displays a quirky and brusque sense of humor. For example, when a chimera threatens Zach as he fumbles trying to interpret some data, Milton bristles, “Look, lizard . . . . Three weeks ago this ape thought that kurtosis was a dental hygiene problem; all things considered, we are moving swiftly.” Later, Milton even congratulates Zach for sticking with it, giving him one of the only straightforward compliments in the whole book: “You are the best student I’ve ever had. I have taught many brilliant scientists, but they are naturals . . . . You are different: You find this hard, people have told you that you can’t do it, but . . . you’ve never given up.”

Field’s world-building and character development in the story animate the often contentious matter of attempting to separate objectivity from subjectivity, science from art, realism from relativism, logic from intuition, and rational thought from emotion. After all, Milton advises against dichotomizing continuous variables, saying it is “rarely sensible.” Through depicting his characters’ struggles, Field shows that both sides of each of these dichotomies are necessary for solving problems well—and that when the opposing sides are at odds, problems may not be solved well and can become more polarizing. Field makes this point most vividly when he has Sister Price, a druidic figure who represents a group called the Doctrine of Chance, explain the drawbacks of null-hypothesis significance testing (NHST): “The recipe-book nature of NHST encourages people to think in this all-or-nothing way. The dogmatic application of the 0.05 rule [for p-values] can mislead scientists.” Indeed, this pitfall has led to the current debate among scientists over reproducibility and fishing for p-values below the threshold for significance.

Field drives this point home later in the explanation, making it clear that despite claims that this type of analysis is more objective and less biased, it is not necessarily so. He has Zach realize that “the scientist’s intentions before data collection affect the actual value of p.” From here, Field guides the narrative into a lesson on effect sizes and Bayesian statistics, a realm of analysis that is not explored in detail in all statistics textbooks. In the story, a cult has emerged around NHST, traditionally considered a gold-standard falsifiable test impervious to the effects of bias. The Doctrine of Chance—Sister Price’s cult, which advocates for Bayesian statistics—arose in response. Critical of the traditional method’s shortcomings, they argue that it indeed allows bias to enter by several possible avenues, including flawed experiment design, overestimating the importance of small effects deemed statistically significant, or by outright fishing for significance. The fictional narrative isn’t too far off from the truth, given that these two camps in statistics have been at odds in the past (and occasionally still are). Field avoids the controversy by putting a humorous fictional spin on it, but he also makes it clear that any statistical technique is suspect when it is applied blindly or dogmatically.

The mythology that Field builds shows that he values the importance of art and emotion as a driver for one’s use of statistics and desire to learn it. Indeed, Zach’s tendency to follow his gut feelings comes in handy throughout the story. By showing how all the characters use statistics along with their other skill sets, Field humanizes statistics, depicting it as a tool wielded by people who may be good or bad, are certainly complex, and are not always in agreement about how they see the world.

The fictional story exists in service of the statistics instruction, as the narrative flow is driven by wherever the statistics lessons need to go next. Although on its own the tale would not garner praise from literary critics, it succeeds in making a normally dry read into one that is fun, emotive, and even suspenseful. Field uses fiction to talk about contentious topics in science and statistics in entertaining and indirect ways, and he also uses the story to show that behind every statistical analysis is a plot with characters, each of whom has his or her own worldview, ethics, desires, and emotions. In this way, the book stands out as being especially instructive about the application and interpretation of statistics in the messy real world, in contrast to the many textbooks that show only the application of statistics in an idealized world. Sometimes fiction is the best vehicle for showing us our own reality, even in a field developed to separate facts from fictions.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.