Extreme Microbes

By Shiladitya DasSarma

Salt-loving microorganisms are helping biologists understand the unifying features of life and molecular secrets of survival under extreme conditions

Salt-loving microorganisms are helping biologists understand the unifying features of life and molecular secrets of survival under extreme conditions

DOI: 10.1511/2007.65.224

Seen from the air, the irregular grid of evaporation ponds at the south end of San Francisco Bay in California is a kaleidoscopic quilt of reds and purples. These ponds take their colors from the single-celled microorganisms that live there, strange beings that thrive in concentrated salt solutions.

Such extreme conditions kill almost every form of life on the planet, but not the salt-loving archaea. They are members of an ancient kingdom that existed even before Earth had an oxygen atmosphere. The fact that many archaea live under impossible circumstances—boiling temperatures, lethal radiation, near-complete desiccation—has led scientists to dub them "extremophiles." These organisms may even be capable of hitchhiking through space.

Ron Giling/Peter Arnold, Inc.

As human beings, our intuitive concept of life is influenced by the visible biosphere—temperate terrestrial, freshwater and marine environments. But the microscopic world in a drop of near-saturated brine contains a menagerie of bizarre life forms that defy these conventions. Unlike the extremophiles that have adapted to a single extreme condition, haloarchaea are metabolically versatile. They can grow aerobically (with oxygen), anaerobically (in the absence of oxygen) or phototrophically (using light energy), and can adapt to fluctuations in temperature, pH and metal-ion concentration. They are resistant to desiccation, sunlight and ionizing radiation. As a result, they can be found in anoxic salt marshes, hydrothermal vents, perennially frozen Antarctica and pockets of brine deep underground and under the seafloor.

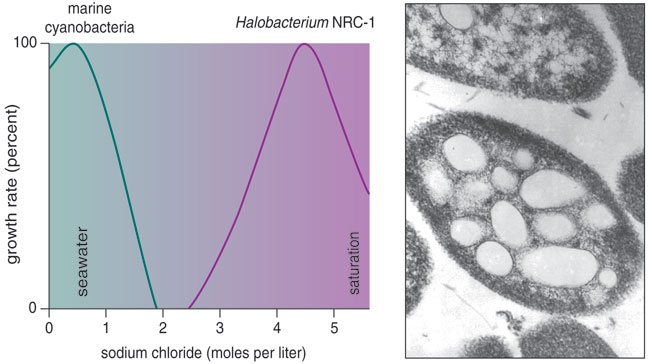

The biggest hurdle to studying most species of archaea is recreating in the laboratory the extreme conditions they need. By contrast, the salt-loving haloarchaea are easily cultivated, and microbiologists have used them in molecular, genetic and physiological experiments. Haloarchaea grow best under hypersaline conditions, from slightly concentrated seawater to near-saturated brine. These attributes, plus the availability of genomic data and tools for molecular manipulation, have elevated them to the status of "model" organisms that shed light on other extremophiles, including other archaea and even higher organisms.

Until the 1970s, scientists believed that all prokaryotes—those single-celled microorganisms that lack a nucleus—were "bacteria." The pioneering work of Carl Woese at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, and his colleagues proved otherwise. Today, prokaryotes are divided into two groups: the "true" bacteria and those evolutionary relics called archaea. Although the two look the same under the microscope, archaea have molecular characteristics that are more similar to nucleus-containing eukaryotes—organisms such as yeasts, plants and animals. These traits confirm that archaea are fundamentally distinct from bacteria.

Micrograph courtesy of the author. Chart by Barbara Aulicino.

Such distinctions notwithstanding, scientists using haloarchaea have made several landmark findings that have wider implications for microbial and multicellular life forms. For example, evidence from haloarchaea helped H. Gobind Khorana at MIT (with whom I began my studies of haloarchaea) to establish the standard genetic code—the Rosetta Stone of biology that allows the information in genes to be used as a blueprint for proteins. The existence of this code is one of the strongest lines of evidence for the unity of all life on our planet.

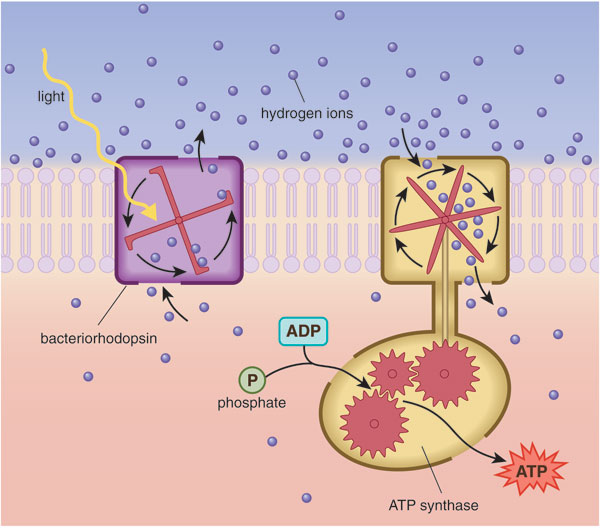

Barbara Aulicino

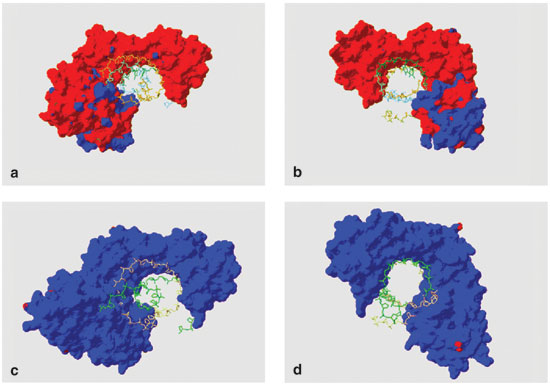

Another early discovery first made in haloarchaea was the protein bacteriorhodopsin. First identified by Walther Stoeckenius of the University of California, San Francisco, bacteriorhodopsin uses photons of sunlight to pump hydrogen ions (protons) out of the cell. This action creates a polarized cell membrane. A separate protein complex harnesses the flow of protons trying to reenter the cell to provide energy—similar to the way a mill wheel harnesses the current of a river to do useful work. In archaea, the purple-tinted bacteriorhodopsin proteins cluster in a specialized region of the cell surface called the purple membrane, where they enable the harvest of light energy for growth under conditions where oxygen is scarce. In classic experiments, Stoeckenius and others showed that light could drive the synthesis of adenosine triphosphate or ATP—the cellular currency for energy transactions—in reconstituted spheres that contained bacteriorhodopsin and ATP synthase. The latter is a key enzyme found in mitochondria, those "powerhouse" organelles present in eukaryotic cells. This work provided irrefutable proof of chemiosmotic coupling, the mechanism of energy generation used by all cellular life.

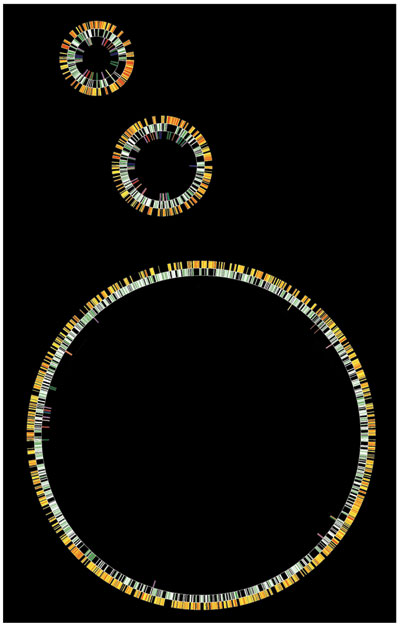

Despite its name (more on this later), an organism that was known as "Halobacterium species NRC-1" was the first haloarchaeon—and one of the first archaea of any kind—to have its genome studied. W. Ford Doolittle at Dalhousie University and my research group (then at the University of Massachusetts Amherst) conducted those early experiments. NRC-1 is in most respects a typical haloarchaeon, widely distributed in hypersaline environments such as the Great Salt Lake. The genome of this species has the unusual property of being spontaneously unstable, such that entire physiological systems, such as the phototrophic purple membrane and buoyant gas-filled vesicles, are sometimes mutated. This curiosity led us to identify a large number of mobile genetic elements—similar to the "jumping genes" described by pioneering geneticist Barbara McClintock in maize. These elements were the first to be discovered in any archaeon. We also found that NRC-1 carries a pair of smaller DNA molecules alongside its chromosome.

The sequence of the NRC-1 genome was completed in the summer of 2000. It was the first complete genome to be sequenced with funds from the U.S. National Science Foundation. The genome consists of a large, circular chromosome (2,014 kilobases) and the two smaller DNA hoops, called plasmids or replicons: pNRC100 (191 kilobases) and pNRC200 (365 kilobases). The pNRC replicons contain many of the DNA repeats that enable genomic rearrangements, including 69 of 91 mobile elements, 33 to 39 kilobases of so-called inverted repeats, which can flip or invert portions of the circles, and 145 kilobases of sequence that are identical in both plasmids.

Barbara Aulicino

All this repetition confounded the computer programs tasked with organizing the overlapping fragments of DNA sequence into a seamless genome. The solution to this problem required extensive knowledge of the structure of pNRC100—knowledge that we had painstakingly acquired in the 1980s and ‘90s by cutting the genome in specific places and analyzing the parts. Later in 2000, we summoned an international consortium of 12 laboratories to meet in Amherst over the winter holidays to identify familiar elements in the genome. Such an analysis was a Herculean task in those days. The computational tools used to analyze genomes were still in their infancy, so we had to write our own computer scripts and manually inspect much of the data.

One of the most exciting discoveries gleaned from that sequence was that the 2,630 predicted proteins were, on average, much more acidic than those of other organisms. The average isoelectric point (a measure of acidity) for predicted Halobacterium proteins is only 4.9. By contrast, the values for nearly all non-haloarchaeal species are close to neutral, a 7 on this scale. Acidic proteins carry strong negative charges, which ought to repel other negatively charged molecules in the cell, such as DNA and RNA. But even proteins tasked with binding DNA (itself an acid)—including pieces of the complex machine called the transcription apparatus, which creates RNA from DNA—turned out to be acidic.

Images courtesy of the author.

Our recent experiments have shown that acidic transcription factors bind DNA with ease in the hypersaline environment inside haloarchaeal cells or isolated in test tubes filled with saline solution. This attraction is remarkable because these proteins and DNA—both negatively charged—ought to repel each other. One possible explanation is that the proteins and DNA work together by sandwiching positively charged ions between nearby, negatively charged side groups. Mutual repulsion between acidic groups helps acidic halophilic proteins to remain in solution under conditions in which neutral, non-halophilic proteins would precipitate or "salt out." Thus, haloarchaea require extremely acidic proteins to maintain cellular functions in a supersaturated-salt environment.

In recent years, the full sequence of the NRC-1 genome has been followed by the publication of five additional haloarchaeal genomes: Haloarcula marismortui, a metabolically versatile species from the Dead Sea; Natronomonas pharaonis, an alkali (high pH)-loving species from the alkaline soda lakes of the Sinai; Haloferax volcanii, a moderately halophilic species from Dead Sea mud; Haloquadratum walsbyi, a square-shaped organism common in salterns; and Halorubrum lacusprofundi, a cold-adapted species from an Antarctic lake. These six genomes currently provide us with an excellent view of haloarchaeal diversity.

The unveiling of the NRC-1 genome spawned questions about as well as insights into the evolutionary history, or phylogeny, of haloarchaea. Although the data confirmed NRC-1 as a true archaeon, the gene that most scientists use as an evolutionary chronometer, the so-called 16S ribosomal RNA, had a unique sequence that prevented easy categorization of the species. This contradiction presented a challenge to the people who name microbes for a living. They had recently renamed several Halobacterium species based solely on DNA sequence, a move that wasn't strictly possible for NRC-1 given the ambiguity. Thus, the name "Halobacterium species NRC-1" has become controversial, fueling ongoing debate about the meaning and significance of the term "species" among prokaryotic organisms. Some scientists go so far as to suggest that the species concept is inappropriate for prokaryotes and should be ditched in favor of "strain" or "phylotype."

Image courtesy of the author.

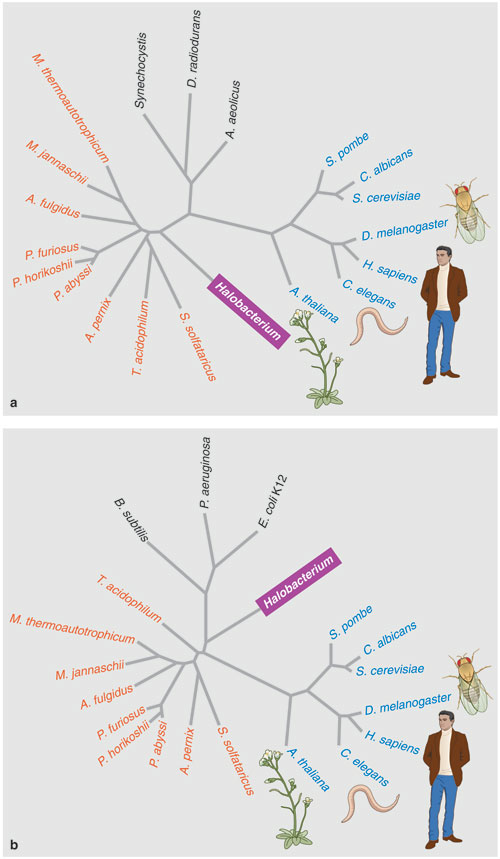

Hoping to find an answer to the phylogenetic puzzle, my coworkers and I compared the entire NRC-1 genome to the few other microbial genomes then available. This preliminary analysis noted interesting similarities between Halobacterium NRC-1 and two true bacteria: the gram-positive, spore-forming Bacillus subtilis and the radiation-resistant Deinococcus radiodurans. But a few years later, after the genomes of dozens of additional species had been added to the databases, the position of Halobacteriumon the tree of life seemed to have moved, either to a spot near the base of the archaeal branch, or, surprisingly, to a branch of the bacteria.

This relocation disagreed with earlier analyses that had placed Halobacterium squarely within the archaea. One possible explanation for the discrepancy is that over time, halophilic archaea may have acquired many genes from unrelated bacterial species in a process called lateral gene transfer. Indeed, some studies concluded that NRC-1 contained nearly as many bacterial genes as archaeal ones, raising the possibility that these unusual microbes began as a kind of prokaryotic jumble.

Barbara Aulicino

Despite uncertainties about the precise history of prokaryotic evolution, evidence for the lateral transfer of genes in the haloarchaeal lineage appears convincing. For example, the genes that enable oxygen-based metabolism in Halobacterium are arranged the same way as those found in Escherichia coli bacteria. The gene sequences are similar to bacteria too. The combination of ribosomal genes that resemble anaerobic archaea and metabolic genes that resemble aerobic bacteria suggests that haloarchaea may have adapted to an oxygen atmosphere by stealing pieces of the respiration machinery through lateral gene transfers from bacteria. Presumably, such events occurred very early in Earth's history when photosynthetic cyanobacteria first began to oxygenate the atmosphere. However, the possibility of multiple transfers, including more recent ones, cannot be ruled out.

A relatively modern example of lateral gene transfer in Halobacterium NRC-1 comes from the gene that encodes arginyl-tRNA synthetase (ArgS), an enzyme essential to the manufacture of proteins. The closest cousins to the ArgS protein from NRC-1 are found among ArgS proteins from bacteria, not those from other archaea or haloarchaea—a puzzling situation, given that NRC-1's presumed archaeal ancestors predate bacteria. The most plausible scenario is that following the capture of a bacterial gene that encoded ArgS, the archaeal gene was lost in Halobacterium NRC-1.

ArgS isn't the only example of this kind. Based on predictions from the genome sequence, about 40 genes in the two pNRC replicons encode essential proteins, including those that make DNA and RNA, and those that use oxygen for cellular respiration. Since the cell can't do without these genes, the pNRC replicons that contain them may be more accurately labeled minichromosomes than plasmids, which are defined by their dispensability. In NRC-1, the plasmids serve at least two important functions: as reservoirs for captured genes and as vehicles for the lateral transfer of those genes. And when those genes are essential for survival, their transfer may lead a prokaryotic replicon to evolve from a plasmid into a chromosome.

One of the most interesting and still unresolved evolutionary questions about halophiles centers on the origin of bacteriorhodopsin, the protein component of the purple membrane. Bacteriorhodopsin is related to mammalian rhodopsins and like them contains retinal, a substance that is, as the name suggests, important in enabling the eye's retina to perceive light. Halobacterium NRC-1 and some other haloarchaea have other retinal-containing proteins too, including halorhodopsin, which pumps chloride ions across the membrane, and photosensory rhodopsin, which can discriminate between useful and harmful sources of light and control the cell's swimming behavior.

Scientists still debate the evolutionary history of these ancient retinal-containing proteins. Although their initial discovery in haloarchaea suggested for a time that such proteins were unique to this group, recent surveys have found similar proteins in many other bacteria and in eukaryotes. Therefore, these proteins may have arisen before archaea, bacteria and eukaryotes first diverged hundreds of millions—perhaps more than a billion—years ago. Alternatively, the genes encoding retinal-containing proteins may have passed by way of lateral gene transfers into planktonic bacteria, some fungi and haloarchaea.

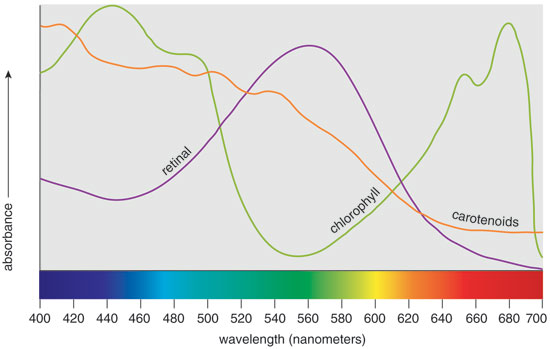

Although the phylogeny of retinal-based pigments remains inconclusive, it's intriguing to think that they coevolved with chlorophyll-based pigments. Comparing the visible-light absorption patterns of the pigments, it's clear that retinal and chlorophyll have nonoverlapping, complimentary spectra. The co-evolution hypothesis argues that simpler, retinal-based use of sunlight as an energy source evolved in microorganisms that dominated during the anaerobic, "purple phase" of the planet's existence. Later, more complex pigments based on chlorophyll could have evolved to harvest light from regions of the solar spectrum not absorbed by the preexisting species. The success of this strategy led to the "green phase" of Earth's evolution and the attendant oxidation of its atmosphere through photosynthesis—changes that displaced most retinal-based microorganisms. Although speculative, such a scenario suggests that retinal-based nourishment from sunlight is one of the oldest metabolic systems on Earth.

Haloarchaea endure many stressful conditions that kill other microbes. For instance, Halobacterium NRC-1 can withstand intense solar and ionizing radiation that in most organisms causes widespread damage to DNA. This feat is possible because the cells produce additional pigments, such as the red-orange carotenoids, to help shield the genome. NRC-1 also contains a double dose—both the bacterial and eukaryotic versions—of the enzymes used for DNA repair. Photo-lyase reverses the damage caused by ultraviolet radiation during the day, a process known as "light repair." Exposure to UV light also triggers the production of a recombinase enzyme that aids DNA repair by promoting homologous recombination (using a good copy of the gene to fix the damaged copy). A third enzyme, exinuclease, snips out bits of damaged DNA altogether. Recombinase and exinuclease are critical for "dark repair," which takes place at night when cells can spend their energy fixing sun-damaged genomes. High-energy radiation and desiccation produce a different type of genetic damage in which both strands of the DNA backbone are broken. Such irradiated cells also make copies of the so-called replication protein A, which binds to exposed, single-stranded DNA, as well as to recombinase, and helps repair genetic damage.

Toxic metals and fluctuating ion concentrations also elicit changes in gene expression that promote survival in Halobacterium NRC-1. For example, cells resist the toxic effects of arsenic by turning on a cluster of genes encoding enzymes that alter the metal's oxidation state and prepare it for active transport out of the cell. The identity of the pump itself remains a mystery, which suggests the existence of a novel mechanism in archaea. Another gene near the arsenic cluster seems to be part of a second detoxification system, which transforms arsenite to a volatile form, trimethylarsine.

NRC-1 responds to low oxygen levels in several ways. One is to induce the production of gas-filled vesicles that enable the cells to float to aerobic zones in the water column. But under strictly anaerobic conditions, cells shift to an alternate means of energy conversion that uses dimethyl sulfoxide, produced by other microbes, and trimethylamine N-oxide, produced by fish, to carry out anaerobic respiration. NRC-1 also responds to oxygen starvation by increasing the production of bacterio-opsin, the protein component of the bacteriorhodopsin used for phototrophic growth. The synthesis of bacterio-opsin is linked to levels of the retinal pigment, and the two molecules react to form a single complex. Indeed, the genes that encode the first and last steps of retinal synthesis and the nearby sensor-activator gene are all coordinately induced under low-oxygen conditions.

Scientists don't completely understand how NRC-1 regulates different suites of genes in response to environmental stresses, but my coworkers and Irecently proposed a mechanism to explain some of that complexity. Our hypothesis is that two general transcription factors, TBP and TFB—which are sometimes overlooked as rather dull, invariant backdrops to more dynamic processes—are themselves acting as regulators. Although the TBP and TFB proteins are usually encoded by single genes in archaea and eukaryotes, Halobacterium NRC-1 carries six genes for TBP and seven for TFB, suggesting the possibility of many different combinations of TBP and TFB during transcription. Specific pairs may activate sets of genes that are intended to work in concert, by way of regulatory sequences found near the genes in question. Other scientists have proposed a similar mechanism to explain the choreography of organ development in some higher organisms. We recently saw evidence of just such a novel regulatory mechanism for haloarchaea, which likely evolved to deal with the stresses and dynamics encountered in their hypersaline environment.

Because haloarchaea tolerate so many forms of environmental stress, I have proposed, along with other scientists, that they are candidate "exophiles"—organisms that might survive on Mars or other planets. The same durability could enable haloarchaea to survive the period of deep-space travel between planets, perhaps encased in salt crystals, which would shield them from some of the damaging radiation. Recently, the European Space Agency found that a strain of Haloarcula survived for several weeks in deep space—longer than any other organism that was still capable of dividing. This finding is consistent with the observed capacity of Halobacterium NRC-1 to withstand desiccation and radiation in laboratory studies. It also supports the findings of geologists who have isolated haloarchaeal DNA similar to that of NRC-1 from halite (salt) deposits more than 10 million years old.

Some of the chunks of Martian rock that have fallen to Earth as meteorites, including the one that fell on Shergotty, India, and the one that fell on Nakhla, Egypt, have contained halite salt crystals. Thus, it's conceivable that meteorites could act as vehicles for the interplanetary transport of haloarchaea. In this context, it's understandable that the public has been keenly interested in recent reports that halophilic microbes were still alive after being trapped in tiny pockets of brine for hundreds of millions of years—reports that are currently beyond the reach of rigorous scientific validation. Yet the range of haloarchaeal adaptations to daunting conditions suggests that it is still premature to dismiss the idea of Martian life out of hand. There is little data that either support or refute the hypothesis that Earth has exchanged forms of microbial life with other celestial bodies at some point in its history. For now, the fact that Earthly forms of life could exist on other planets is remarkable enough all by itself.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.