Little Interactions Mean a Lot

By Roald Hoffmann

Noncovalent bonds are weaklings compared to familiar chemical reactions, but they add up to strongly influence the shape and behavior of molecules.

Noncovalent bonds are weaklings compared to familiar chemical reactions, but they add up to strongly influence the shape and behavior of molecules.

DOI: 10.1511/2014.107.94

I used to like my energies big. Strong chemical bonds and large energetic reactions are dramatic and easy to observe and understand. They make fire burn and drive much of industrial chemistry. But a lot of the world around us and inside us works on more subtle atomic and molecular interactions that operate on energy scales 10 or 100 times smaller.

Consider the following phenomenon: You dip a paintbrush into water, or watch Esther Williams jump into a pool—as she often did with staged abandon, wonderfully coiffed, when I grew up and first went to the movies. (If Esther Williams means little to you, substitute the singer Rihanna.) When the paintbrush or Esther emerge from the water, their hairs, to put it colloquially, are stuck together. The first instinctive reaction is to say that the hair clumps up and that the brush acquires its point because they are wet. But hold on: Look at the brush while it is in the water—the hairs remain apart, and you can’t get wetter than that!

So, it’s not wetness that makes the hairs clump. Rather, it’s the small hydrogen bonding forces between water molecules, which are greater in number when as many water molecules as possible are near each other. The macroscopic manifestation of this bonding is called surface tension: It’s why water droplets form in clouds, and it’s what allows whirligig beetles to scoot on the surface of ponds. It’s what C. V. Boys calls “the skin of the water” in his wonderful 1911 book Soap Bubbles: Their Colors and Forces which Mold Them, which Ben Widom brought to my attention. The energy of hair plus water is lower when the hairs clump together; the small hydrogen bonding forces that bring water molecules together carry along the hair strands with them.

Such weak, or noncovalent, bonds are ubiquitous, and their prevalence gives them a power that belies their modest nature. In water, they influence the global geology and climate of the Earth. In organic molecules, they regulate how proteins fold and hold together DNA’s double helix. Despite my partiality for big energies, the power of accumulated small energies have prompted me to question my prejudices.

What is big from one perspective is small from another, and energy can be measured in a variety of ways. By “big energies,” I mean those equal or greater than about 1 electron volt per molecule, which is equal to 23.1 kilocalories per mole, or 96.5 kilojoules per mole. A photon of yellow light has an energy of about 2.1 electron volts.

In theoretical chemistry, I was looking for molecules that in one bonding arrangement could be at least 1 electron volt per molecule more stable than in an alternative configuration, or that would require an activation energy (the barrier to a reaction taking place) that is at least 1 electron volt lower than a competing reaction, thus proceeding much more expeditiously. I knew that the strength of the hydrogen bonds that hold together the base pairs of the DNA in my body are, per pair of atoms involved, at least an order of magnitude smaller than 1 electron volt. So are the “dispersion” forces (more on these in a moment) that make the molecules around me—be they acetaminophen or ethanol—solids and liquids rather than gases.

Quantum mechanics, through accurate solution of Schrödinger’s wave equation for the energies of the matter waves, is needed to describe theoretically the reactants and products in a chemical reaction. I think the reason I favored the large gobs of energy was that my way of solving Schrödinger’s equation was … lousy. (I’m just a quantum mechanic—it comes with the chemistry.) I could only get approximate energies, plus or minus an electron volt of the solution. For energetic reactions that is good enough.

Yet I knew that energies much less than 1 electron volt could make a big difference in fundamental molecular processes, such as making functional proteins. Every molecule solves Schrödinger’s equation exactly, without worrying about it. Nature’s way of exercising decisive control is through the accumulation of many small differences. Once proteins of some complexity (containing more than 100 amino acids) became the toolkits for making and breaking bonds, then small differences in the folding and variations in the kit components (the amino acid sequence) create local environments (active sites) that are exquisitely tunable.

Through accumulation of small interactions, Nature creates an effective qualitative difference in the rate of cleavage of a carbon–carbon bond (C–C), the geometry of binding oxygen (O2), or the firing of a nerve signal. There is room in biology for large dollops of energy: Witness the two photons used in photosynthesis. But soon even that large influx of energy is partitioned in a cascade of many small reactions. This partitioning maximizes efficiency for the overall process, getting the energy of the photons into the energy courier of the cell, adenosine triphosphate (ATP).

Even if I was unable to calculate energies exactly, I’ve grown to appreciate the cumulating logic of the small. The wondrous world of the unromantic diminutive adding up to something big is increasingly important as the applications of nanotechnology and the potential for quantum computing unfold.

In addition to the hydrogen bonding mentioned earlier, there are other small forces, like multipole interactions that convert an asymmetry of the way electrons are distributed in a molecule into forces between them. And dispersion forces, which are responsible for molecules and atoms condensing and eventually freezing. These are all essential, small, structure-determining factors called noncovalent interactions, to distinguish them from “real” chemical covalent (or ionic) bonds, which are 10 or more times stronger. For example, the covalent bonds that hold methane (CH4) together are achieved when each hydrogen atom shares an electron with the carbon atom; these bonds are much stronger than the hydrogen bonds that cause wet hair to stick together, and so it takes much more energy to break apart methane than strands of hair held together with bonds between water molecules.

There are volumes written on each noncovalent force, and yet people still disagree on their origins and even more vehemently on the relative contribution of the interactions mentioned above to the energy of the molecule as a whole. The energies involved in such interactions are characteristically small, tending to be less than 5 kilocalories per mole of atom pairs involved. I don’t want to lump them together; they are so interestingly different. But here I must, while saying just a few fuzzy words on two of them in particular.

Dispersion forces are also called van der Waals interactions. German American physicist Fritz London provided the quantum-mechanical view of these in 1930, so sometimes they are referred to as London dispersion forces. Their physical origin is in the correlated motions of the electrons in two interacting atoms or molecules: A fluctuation in the electron distribution in one induces a local asymmetry of electrons in the other. Carefully averaged over space and time, an attraction emerges that falls off as 1/ R6, where R is the separation between the nuclei of the atoms involved.

Dispersion forces can be tiny, as is the case for two helium atoms, which is why helium cannot be frozen at ambient pressure, or large for big molecules, such as the alkanes in candle wax or aspirin. (The forces are related roughly to the number of “exposed” atoms capable of coming close to each other). However big they are, the 1/R6 falloff ensures that they are relevant only when atoms get close to each other. But not too close, because then they repel each other.

Prototypical hydrogen bonding, the noncovalent bond associated with wet hair and brushes, occurs when the hydrogen of a polar oxygen–hydrogen (O–H) or nitrogen–hydrogen (N–H) bond comes near an electron source, typically the lone pair of electrons of a nearby oxygen or nitrogen atom. The chemistry community sees these bonds most commonly as the result of an ionic attraction between the positively charged hydrogen (in the N–H or O–H bond) and the negatively charged electrons of the lone pair on a nearby N or O. (I don’t agree, but that is a story to be told elsewhere.)

Despite such disagreement on origins, there is no disagreement at all on the magnitude of the energy involved, generally less than 5 kilocalories per mole. Small again, but there are oh-so-many of them.

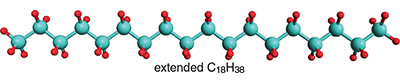

Small energies play out in other interesting ways in some of the simplest organic molecules: the unbranched long-chain hydrocarbons, such as the liquid to waxy “normal” alkanes, which are written chemically as CH3 (CH2)nCH3. The molecules in gasoline belong to this family with n = 6 or so; increasing n from six leads to diesel fuel, jet fuel, oil, and lubricants. When alkanes become solid, which happens for still higher values of n, there isn’t much use for them, except as candle wax. The unbranched, or anti conformation, is energetically preferred, as shown for C18H38 below.

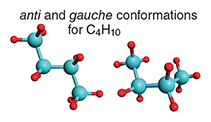

One wants to know the preferred shape of a molecule to understand its chemical personality—how it behaves, and how it reacts. A conformation is a geometry of a molecule that differs from another one by rotation around only single covalent C–C bonds. At each interior point in the hydrocarbon chain, for every four carbons, a choice is available between an extended conformation, which chemists refer to as all- anti, and two mirror-image curled-up forms, known as gauche conformations. The all- anti and one of the two gauche conformations are shown below for lighter fluid, or n -butane, C4H10.

The energy difference between the two conformations is truly minuscule. The gauche geometry is merely about one kilocalorie per mole in energy above the global minimum of the anti form; this is just 1/40th of the energy of a photon that is absorbed by a chlorophyll molecule in photosynthesis.

The two “conformers” are related by 120 degrees of rotation around the central C–C bond. Here’s another small energy at work, now controlling the geometry of a molecule. That rotation faces a small barrier; the reasons for it are still rousing my fellow theoreticians to much debate. But there is little uncertainty about its value; it is around 3 kilocalories per mole. Because there are two gauche forms, these conformations are favored by entropy. So, only as temperature approaches zero kelvin would one have the frozen-in anti conformation of n -butane as the only form present. At room temperature in a liquid or gas there is, however, enough energy from molecular collisions to have a significant number of n -butane molecules in the gauche conformation.

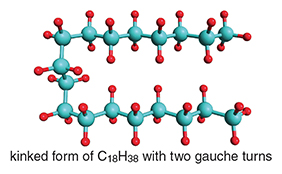

Suppose we have two conformations of a longer-chain, normal alkane, say C18H38. The all- anti, extended one is shown above, and a kinked form is shown at right. The turn in the middle of the kinked chain is achieved by incorporating two gauche “turns” (play with a model, and you will see it can be done).

That kinking costs energy, but only a wee amount—each gauche turn has an associated penalty of about 1 kilocalorie per mole. What is accomplished by the kink is visually apparent in the depiction below; the second part of the chain is brought near the first. In that conformation, or actually in a family of conformations looking roughly like that, there is a new source of stabilization that is unavailable in the extended, all- anti geometry: attractive dispersion forces between the two parts of the chain. The more chance for hydrogen atoms to come close to each other, the more stable that arrangement, so the folded molecule is more stable.

Small as they individually are, dispersion interactions add up. For an isolated molecule, for some n in CH3(CH2)nCH3 for example, the energy lowering (stabilization) in dispersion interaction will win out over the increase in energy (destabilization) in kinking, the latter accomplished by two or more gauche conformations along the chain. The molecule that I thought would be “straight” when I forgot to consider dispersion forces actually prefers energetically to be kinked.

To my knowledge, Jonathan Goodman first wrote down this idea in 1997. Theory in his and others’ hands confirmed the notion: For CH3(CH2)nCH3, the crossover from extended to kinked (and eventually curled in a more complex way) comes at around n = 16, or 18 carbon atoms. Remarkably, the experimental proof for this hypothesis has recently come forward, in work by N. O. B. Lüttschwager and colleagues.

Noncovalent bonds abound in nature, but there are clever new ways to exploit them artificially as well. Separating the small from the large is important in science, for instance, in gel electrophoresis and centrifugation. The development of nanofilters has opened up new ways to quickly separate small particles from even smaller ones, but most do not exploit noncovalent bonds because materials that rely on weak interactions often are not stable.

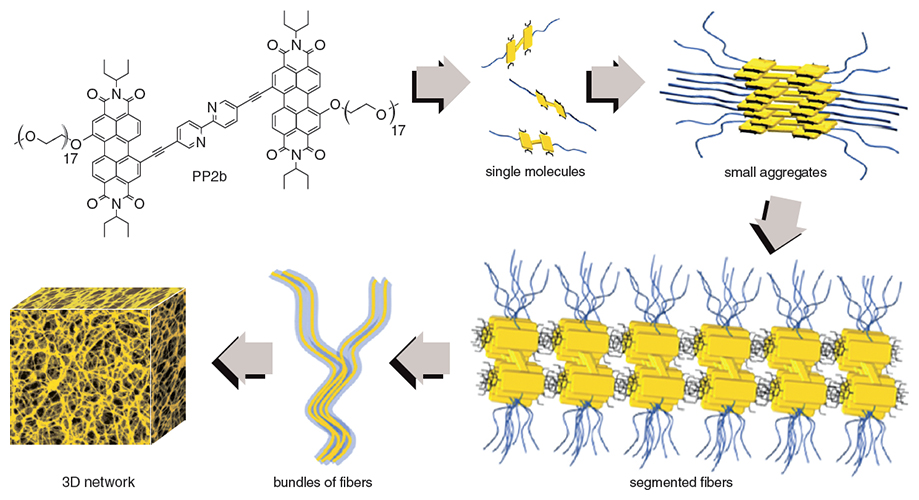

Illustration adapted by Tom Dunne from an image courtesy of Boris Rybtchinski.

In 2011, Boris Rybtchinski and his collaborators at the Weizmann Institute of Science made a nanofilter held together by noncovalent bonds. The nanofilter has the additional intriguing property of being recyclable.

To make this nanofilter, Rybtchinski and colleagues took a beaker with a solution of a molecule in it, call it PP2b (you don’t want to know its systematic name), and poured it on a membrane, essentially an inert support. PP2b transformed into a colored gel on the support. That gel could separate the two kinds of nanoparticles. Small ones could go through readily, whereas large ones stayed on top. Then, when they poured a mixture of water and ethanol on the filter (roughly the strength of a good vodka), the gel dissolved and passed through the membrane, along with the large nanoparticles. PP2b and the large particles were easily separated, and then the PP2b was ready to be used again.

A balance of hydrophobic and hydrophilic bonding—that is, two types of weak, noncovalent bonds, working together—explains the magic of supramolecular polymers such as PP2b. Hydrophobic and hydrophilic are terms describing the proclivity of molecules or pieces of molecules to prefer, on a microscopic level, an aqueous environment or its opposite, represented emblematically by a long hydrocarbon chain.

If a piece of a molecule is polar, a local separation of positive and negative charge, that polarity will be attracted to a watery environment; a nonpolar segment would prefer the hydrocarbon surroundings. Soaps and detergents work through providing regions of both hydrophobic and hydrophilic bonding; the balance is also important in the preparation of many good things in this world, such as mayonnaise.

The platelet-like hydrocarbon rings in the middle of PP2b (see above) are nonpolar; the CH2CH2O, repeated on average 19 times, is the polar part, which likes water. In a number of solvents, including the common THF (tetrahydrofuran), PP2b is a biggish molecule with two tails. But in the presence of substantial amounts of water, the hydrophilic and hydrophobic interactions turn on, because the hydrophobic parts (the central organic platelets) want to be near each other.

The organic platelets, with pendant ethylene glycol tails, aggregate. On a molecular level one sees the formation of segments, then fibers, which can be viewed with a scanning electron microscope.

The performance of PP2b in solution is pretty neat—usually, one adds water and a solid dissolves; here, Rybtchinski and his colleagues added water, and a gel, a solid-like material with a lot of water still in it, formed. That’s the filter.

Notice that hydrogen bonds and dispersion forces are involved; small interactions that, as I said, are 10 to 30 times smaller than the energies of carbon–carbon, carbon–oxygen, or carbon–hydrogen bonds. Yet these small interactions add up, with a vengeance, to create three-dimensional aggregates, the network of fibers. This network is robust—stable to approximately 70 degrees Celsius—until you pour alcohol on it.

After all that, I still like my energies big. And, for that matter, I also like to follow individual molecules through their collisions with other molecules as bonds are broken and remade. My desire for the big and the particular—and my resistance to calculating averages over billions of molecular trajectories—comes with a price, however. It prevents me from moving from the angstrom scale of molecules to the macroscopic world where we experience the practical results of chemistry. It keeps me away from ferromagnetism and viscosity, and from Esther Williams’s interaction with water.

It’s an irrational desire, I know. The accumulation of tiny differentials rules nature. How could it be otherwise in a molecular world where it takes 6 x 1023 water molecules to make a single slurp of refreshing liquid? Change happens more readily through shuffling small pieces than by completely rearranging big ones, as evolution has discovered.

On the human level, as in chemistry, a big number of small actions can bring about large-scale change: Within our imperfect approaches to democracy, the small contributions of many can accomplish real change—be it in the abolition of slavery, the empowerment of women, or the limitation of automobile emissions.

I waver. It is so clear that small interactions of molecules can hardly be ignored, even if a weak theoretician with imperfect tools decides he cannot work on them. I like stories—science, and not only science, lives in them. The stories of modern chemistry that I have retold here show ever so clearly that aggregation, the action of many tiny gobs of energy in concert, can lead to essential change and a tangible, macroscopic consequence.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.