Less in Space

By Paulo C. Lozano

It’s smaller than a breadbox and the biggest thing in satellites since Sputnik.

It’s smaller than a breadbox and the biggest thing in satellites since Sputnik.

DOI: 10.1511/2016.122.270

October 4, 1957: The Soviet Union rockets the world into a new and exciting era of space exploration. Sputnik, a relatively small satellite weighing about 80 kilograms and incapable of maneuvering or determining its position, orbits the Earth with just enough battery power to send an occasional radio signal. It clears the way for many applications to come, from weather forecasting and global communications to GPS navigation and interplanetary probes.

It is formidable how quickly the field of space technology has evolved in the years since Sputnik’s launch. Modern civilization would find it very difficult to operate without the many services that satellites orbiting the Earth bring, and many fields of science would be crippled without spacecraft peering toward the farthest objects in the universe and travelling to planets, moons, asteroids, and comets in the Solar System.

Despite their historical successes, space technologies remain out of reach for most: Like older Tesla automobiles, they are prohibitively expensive; like the new Tesla 3, demand is too high. It currently costs between $10,000 and $20,000 for every pound of material sent to low Earth orbit. Such costs make it difficult to innovate and take risks. And while satellites have become more and more capable, their uses and those who design and build them have remained, for the most part, the same.

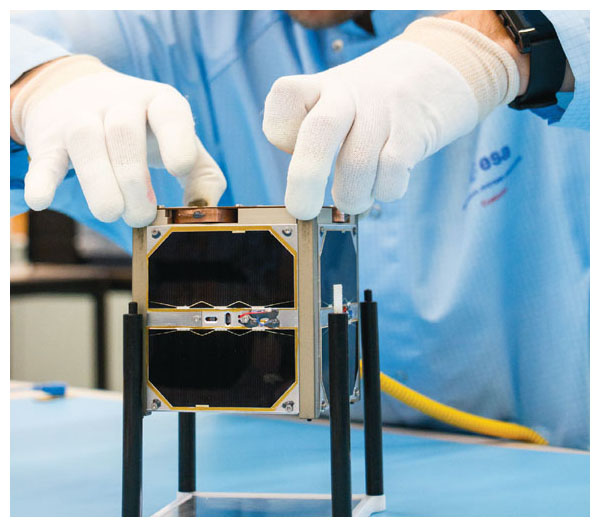

Photograph courtesy of Rasmus G. Sæderup.

Recently, this situation started to change. About 15 years ago, a group of academic and industry researchers introduced the concept of standardized small satellites. Bob Twiggs, then of Stanford University and now at Morehead State University in Kentucky, and Jordi Puig-Suari of California Polytechnic State University, defined the size and shape of these satellites to be so tiny that they could cheaply go into space as secondary cargo every time a large rocket lifts off. This particular standard, so far the most successful, is called a CubeSat.

Each CubeSat unit, or “U,” measures 10x10x10 centimeters and weighs about 1.5 kilograms. They can be scaled up. Double the length, and you have a 2U unit; triple the length, and you have a 3U unit. Kilo for kilo, they cost about as much as larger payloads, but they have greater and more flexible capabilities. Now practically every university with a space systems program is working on CubeSats.

A key aspect in the success of the satellites is the way they are launched. They are carried inside a Picosatellite Orbital Deployer, or POD, which can eject them from the launch vehicle via a spring-loaded mechanism. Once the POD is qualified for flight, the design can be used again and again at practically no added development costs.

Although the number of all other satellite classes has remained fundamentally flat for years, the number of CubeSats placed in orbit has increased dramatically, with roughly 100 launched each of the past three years. Still, recall how small a U is and the challenge of making its contents as valuable as those of a 1,000-kilogram satellite. The laws of physics impose limits on the smallest functioning size of devices such as telescopes and antennas. CubeSats’ dimensions and mass are so small that packaging components becomes a significant task.

Fortunately, commercial computer and sensing technologies have injected tremendous innovation in parallel with the development of the CubeSat standard. Thus CubeSats carry much more capabilities in their small envelopes than not only Sputnik but many larger satellites. Today’s CubeSats include power generation and distribution, basic passive temperature regulation, radios, GPS navigation, attitude determination and control, and computers. They also pack miniature high-performance payloads, such as sensitive digital cameras and other small but powerful sensors that can detect X-rays from black holes, high-energy particles, space weather, distant stars and planets, and the structure of the Earth’s magnetic field.

The future holds great promise for these little space systems. In particular, given their low cost and development times, they are ideal for specific tasks. They can also be deployed in constellations, large numbers of individual units that perform coordinated tasks at a substantial cost savings. As more and more CubeSats are put into space, additional applications will be found for them, spurring innovation that will attract new players and ideas. For example, the company Planet Labs observes and photographs the Earth using a constellation of 3U CubeSats called “Doves,” which provides a refresh rate over given locations that is simply not possible with larger monolithic satellites. The resolution is lower, but many applications, particularly civilian ones, do not require the ultra-high detail of large military systems.

Despite the great success of CubeSat-type satellites, their continued improvement is hampered by their relatively poor communications and inability to maneuver once in space. Both functions are difficult to miniaturize.

For one, communication systems require power, and practically all data are currently transmitted using radio frequency. Here, satellite size truly matters. Power comes from solar cells, so smaller satellites generate less power. The distance between sender and receiver also plays an important role. For a given amount of power, the farther away you are, the slower the communication rate will be. Having a large antenna that focuses this power helps to increase data rate at constant power, but once again, small CubeSats rarely carry more than a flat patch antenna that distributes an unfocussed signal evenly in all directions. This important limitation will become more critical for CubeSat missions with very long transmission distances, such as those used in deep space travel.

These little space systems can be deployed in constellations, performing coordinated tasks at substantial cost savings.

An elegant solution to this problem is the use of low-power laser communications. This method is the equivalent of using an optical fiber on the ground to communicate large amounts of data. Larger spacecraft have used laser links, which require precise control of the satellite’s position and orientation, as any deviations from the line of sight of a narrow laser beam degrade the link quality. Given the lack of fine actuators in CubeSats, the use of laser communications is particularly difficult. Nevertheless, there is significant progress in this direction, and it is very likely that this capability will be demonstrated and available to the community in the near future. NASA and The Aerospace Corporation of El Segundo, California, started testing the technology last year with its Optical Communications and Sensor Demonstration on AeroCube-7.

CubeSats must also contend with the challenge of getting where they need to be. Just as hitchhikers rarely get driven to the door, CubeSats travel as secondary cargo. They have no say in their final orbit, which is determined by the prime payload requirements. Thus, the first motivation for having a propulsion system on board is to allow these small satellites to change their orbits. Once this capability is available, however, they could achieve many more things, such as the deployment, positioning, and maintenance of constellations. Such missions could enable laser communication networks, satellite docking and repair, and distributed sensing, in which satellites share tasks.

Improved mobility will also help these small satellites steer clear of trouble. Clearly, the relative ease of putting smaller things into orbit could quickly increase the number of objects that could turn into space debris, which is a very important concern for the whole spacefaring community. Space debris colliding with functional satellites at velocities of kilometers per second is devastating, regardless of its size. Propulsion on these little spacecraft would allow them to maneuver to prevent collisions and deorbit after their missions are completed.

Propulsion can be divided into two types, chemical and electric. The underlying working principle is the same: As they eject propellant at high speeds, the satellites are subjected to Newton’s laws of action and reaction. Both systems need to carry “fuel” or propellant into orbit, but the amount of force for a given quantity of propellant is about 10 times greater with electric thrusters. The downside is that, in addition to the propellant itself, electric rockets need to carry a power source. Furthermore, the mass of this source grows with power, which limits the amount of force that electric thrusters can produce to a very gentle push. Nevertheless, there are many missions that do not require strong forces, so electric thrusters could bring significant savings in mass and volume, both of which are critical for small satellites.

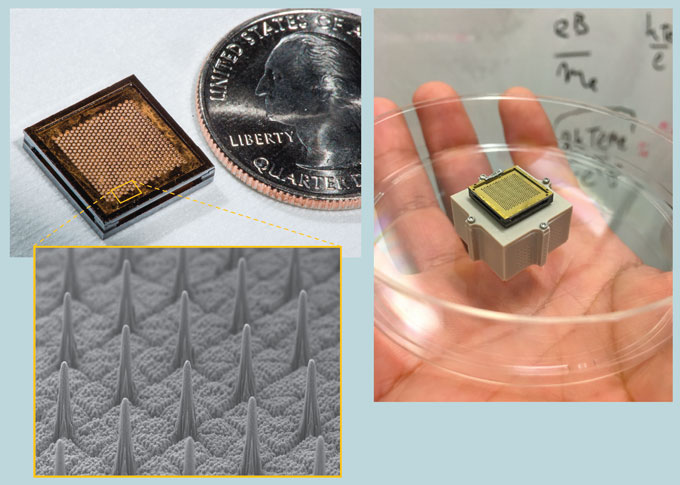

Images courtesy of M. Scott Brauer (left) and Paulo C. Lozano.

Most electric propulsion devices produce their exhaust through gas ionization. Essentially, a neutral gas such as xenon is injected into a chamber where an electric discharge forms a plasma —a collection of lightweight electrons and much heavier positively charged ions. The ions are ejected from the chamber using an electric field, producing thrust, while the electrons are also pumped out to join the ion beam and prevent potentially hazardous spacecraft charging. In very simple terms, the larger this chamber is, the more ionization will occur. That’s not good news for their possible miniaturization, as volume in 1-liter CubeSats is a precious commodity. Indeed, as plasma thrusters are made smaller and smaller, their performance degrades. In general they become less efficient, requiring more power for the force they produce, and are more difficult to package in the tight space of a mini satellite.

Just as hitchhikers rarely get driven to the door, CubeSats get no say in their final orbit, so onboard propulsion allows them to change their position.

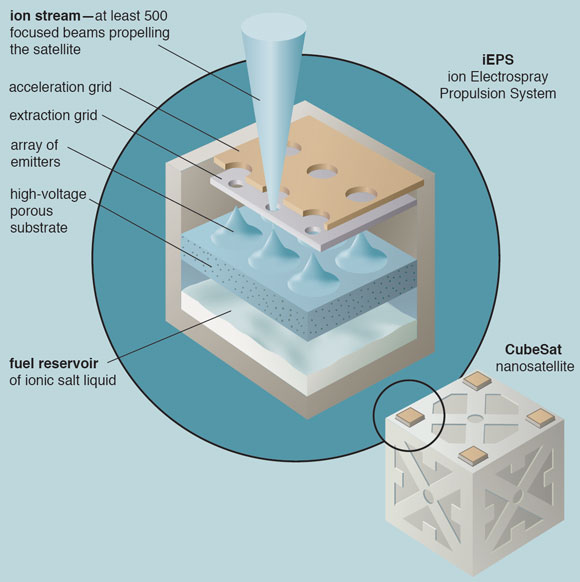

An alternative to these devices, currently under development in my laboratory at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, is called the ion Electrospray Propulsion System, or iEPS. In contrast with plasma thrusters, iEPS works with an ionic liquid—a salt with such a low melting point that is liquid at room temperature. Because of their positive and negative ions, these liquids are relatively good electric conductors, and their strong molecular bonds mean they also can be exposed to the vacuum of space with practically no evaporation. Furthermore, ionic liquids have very wide thermal stability, ranging from about –100 to 400 degrees Celsius. When exposed to very high electric fields, the same ions that compose the liquid can be evaporated directly from its surface. Once out, these ions accelerate rapidly, reaching velocities in excess of 30 kilometers per second, producing thrust. Because the ions come out from the liquid surface, there is no need for an ionization chamber, which means that the devices can be very small. That’s perfect for nanosatellites. Meanwhile, their conversion efficiency of up to 80 percent is higher than plasma thrusters.

One of the main issues with this approach is that the magnitude of the electric fields required for ion evaporation is more than a billion volts per meter. This is about 1,000 times the field required to electrically break down air in atmospheric conditions during, say, an electric storm. Fortunately, there is an elegant method to obtain a field that intense. When the ionic liquid is held at the tip of a sharp styluslike structure and a voltage is applied between the tip and a downstream electrode, the electric pressure on the liquid could become as strong as the surface tension of the meniscus at the tip. Such balance between electric traction and surface tension makes the normally rounded liquid meniscus conical in shape, with a very sharp apex. This liquid structure is essential to the process. Charges concentrate on sharp edges, so the liquid sharpness amplifies the electric field value until the liquid reaches the threshold for ion evaporation.

A single ion emitter produces forces on the order of tens to hundreds of nanonewtons. That’s very small, even for the smallest of satellites. On the other hand, the region from which ions come is just a few tens of nanometers across. To increase the amount of thrust to the levels required by a particular application, large numbers of individual emitters are assembled in arrays and operated in parallel. For example, the iEPS thruster contains 500 emitter tips that fit in a module measuring just 12x12x2 millimeters. It produces a variable thrust, depending on the applied voltage, between 5 and 20 micronewtons, which is enough to provide adequate mobility to a small 1 kilogram CubeSat. Two of these iEPS modules are operated at opposite polarity to prevent the accumulation of charge in the spacecraft, with that polarity alternating periodically to retain the chemical integrity of the ionic liquid.

The manufacturing techniques in iEPS are similar to those used in the microelectronic industry to build computer chips and other microcomponents. The heart of the device is a porous glass substrate through which the ionic liquid wicks from an upstream reservoir into the emitter tips, also carved in the same porous material. There are no valves, pipes, or active pumping or pressurization in this device and only one control knob, for voltage. Because of the lack of ancillary components other than a power supply, an entire system of at least two thruster module pairs can fit comfortably in satellites as small as CubeSats and still leave enough room for all other subsystems and the payload.

Illustration by Don Ramie

This technology is advancing at a rapid pace and performs very well in laboratory tests. My students, research staff, and I have actuated thrusters in a magnetically levitated CubeSat inside a vacuum chamber, and we’ve performed static tests spanning hundreds of hours of continuous operation. In addition, a demonstration unit was launched into space in 2015 to investigate the fundamental operating principles of iEPS propulsion, and missions using this technology are being prepared for launch before the end of 2016. An MIT spinoff called Accion Systems plans to commercialize the technology.

As the capabilities of CubeSats are improved with new technologies such as iEPS, it is all but certain that we will see new applications emerging and more players and industries using space in ways we have not seen before. It’s a striking contrast to 70 years ago, when space exploration was largely a subject for dreamers. Now a new generation of space scientists and engineers can actually work on real space systems while still in college and graduate school, or even during high school. They’re not dreamers anymore—just big thinkers who also know how to think small.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.