Will We Stop at Nothing?

By Roald Hoffmann

Science and popular culture mix in Brazil's Carnaval

Science and popular culture mix in Brazil's Carnaval

DOI: 10.1511/2005.51.18

When it comes to the popularization of science, you already know the answer for some of us. This is a story of a most unusual intersection of science and popular culture in Brazil, in which I was fortunate enough to play a tiny part. It is also a personal picture book.

Rio de Janeiro's Carnaval is days of raucous celebration before Lent. The highlight is a ritualized competition between neighborhood-based "samba schools" that spend a whole year and a multi-million-dollar budget preparing for a gargantuan, one-time musical production. Massed 3,000-5,000 strong, the vividly plumed members of the school dance through the Sambódromo, an 800-meter-long coliseum devoted to just this purpose. Each group parades for 90 minutes in a choreographed fusion of story, song, dance and dress, tied together by a theme, punctuated with floats, animated by the thunder and syncopated variety of the bateria ("drum corps" is an impoverished translation).

Courtesy of Casa da Ciência at the Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro.

Sambaing down the central avenida, the cultural fault lines between favelas (shantytowns) and affluent districts are momentarily forgotten. All dancers dress in costumes called fantasias, coordinated with the theme and the floats, and sing at the top of their voices the thematic samba of the school, the samba de enredo. Fourteen schools compete in the top league; the lowest-ranking can be demoted to the minors.

I know you are wondering where the science comes in. Well, in 2003, a talented young carnavalesco (the designer of a carnaval parade; yes that's a profession in Brazil) named Paulo Barros proposed to one of the less affluent samba schools, the Unidos da Tijuca, a science theme for the February 22, 2004 parade. No one had gone down this road before—typical Carnaval themes are Amazonia, African or Portuguese heritage, sex, the sea, television stars et cetera. Unidos da Tijuca agreed to the plan, and began preparing for "The Dream of Creation and the Creation of the Dream: Art and Science in the Age of the Impossible."

Courtesy of Casa da Ciência at the Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro.

Paulo Barros then approached the science-outreach group, called Casa da Ciência, at the Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ). The enthusiastic Casa da Ciência crowd loved the idea, and worked with the samba school for a year to get ready. The results showed, from the words of the theme samba to the costumes.

The vast majority of Brazilian scientists, even some who usually left town during Carnaval, were supportive of this incredible opportunity for science to interact with popular culture. The United States equivalent might be a science-themed halftime show at the Super Bowl.

Courtesy of Casa da Ciência at the Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro.

Yet Barros's show was assuredly carnivalesque—not only in its traditional suspension of everyday prohibitions, but also in Bahktin's sense, in its mocking of authority. In some instances, scientific authority was the butt of the joke: The parade included floats and dancers that played to the worst stereotypes, such as a troop of Frankenstein's monsters and a bevy of reanimated mummies.

Courtesy of Casa da Ciência at the Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro.

A month before the festival, the press found a critic who said what you'd expect—that there was a real risk of reinforcing misguided stereotypes in the floats. At the same time, some Carnaval mavens were criticizing the Unidos da Tijuca for their choice of a "difficult" theme. I suspect that the Casa da Ciência people sat down for a strategy session and decided that it might help if a well-known scientist from outside the country would give them needed support. Richard Feynman, who played in a bateria 50 years ago, was unavailable, having died in 1988. I can imagine one of them saying "Who would be crazy enough to so this?" And my friend Antonio Carlos Pavão from Recife probably said "I know, Roald!"

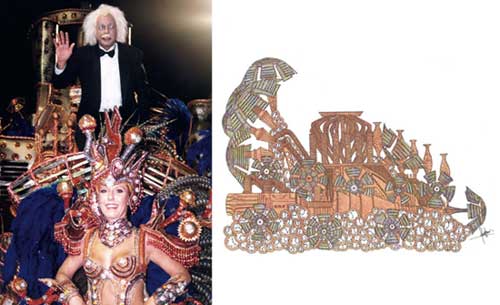

Illustration courtesy of Casa da Ciência at the Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro. Photo courtesy of Roald Hoffmann.

So they asked me, three weeks before Carnaval. As you can tell from the sleek blue denizens of one of the floats (and these are the tame images), Unidos da Tijuca didn't want me for my body. Not for my mind either. True, I thought that the shapes around the bottom of the alchemy and chemistry float were atomic orbitals (the subjects of my research), but they were pills.

Photograph (left) courtesy Marizilda Cruppe/Agência O Globo. Photograph (right) courtesy of Antonio Carlos Pavão.

The samba school wanted me for the publicity I would generate and the good things I would say about the science in the parade. I knew that, and it was fine—I agreed to be used for a good purpose. And I would be in Carnaval: The other scientists and I were all dressed as Alberto Santos-Dumont. Santos-Dumont was the revered Brazilian aviator who, in Paris, pioneered dirigible airships and lay claim to the first sustained, heavier-than-air flight (his biography was reviewed in American Scientist, September-October 2003). The assertion is arguable—everywhere except the U.S., of course, which unconditionally deifies the Wright brothers. The costuming choice made for good newspaper questions for me, the American.

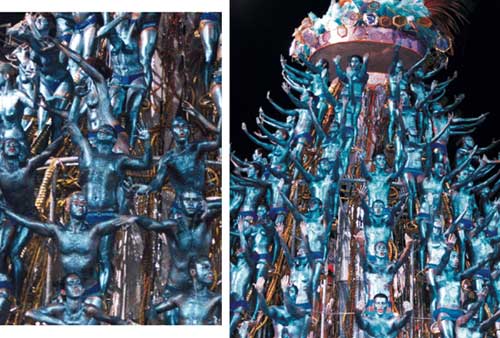

The star of the parade was one of Barros's floats called Criação da Vida, or Creation of Life. One hundred twenty-three young people, spray-painted blue-black, were strapped onto this pyramid, and they performed a spectacular choreographed dance as it moved through the Sambódromo. At times their arms and bodies evoked the helices of DNA and proteins; at times they just celebrated life.

Photograph courtesy of Casa da Ciência at the Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro.

To the surprise of the Carnaval, Unidos da Tijuca won second place. It had never ranked higher than fifth in the top league. Much of the credit goes to Paulo Barros's theme and the Casa da Ciência's efforts. Science will be back at Carnaval in the years to come.

I am grateful to the Casa da Ciência of UFRJ, including Fátima Brito and her dedicated gang, to Unidos da Tijuca (Fernando Horta, president), to Antonio Carlos Pavão of Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Recife, for getting me to Rio, and to Cornell University for paying for the trip.

© Roald Hoffmann

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.