Decoding Light from Distant Worlds

By Kevin Heng

Thousands of exoplanets are known, but the compositions of their atmospheres remain at the edge of our knowledge.

Thousands of exoplanets are known, but the compositions of their atmospheres remain at the edge of our knowledge.

Modern astronomers now consider the discovery of exoplanets so routine that a Nobel Prize in Physics was finally awarded for exoplanet science in 2019. Thousands of exoplanets (planets orbiting other stars beyond our Solar System) are known to orbit stars in our galaxy, but our knowledge of each exoplanet is generally limited to its size and mass. The next challenge is to develop an inventory of the chemical compositions of their atmospheres—and finally discover what kinds of worlds they are.

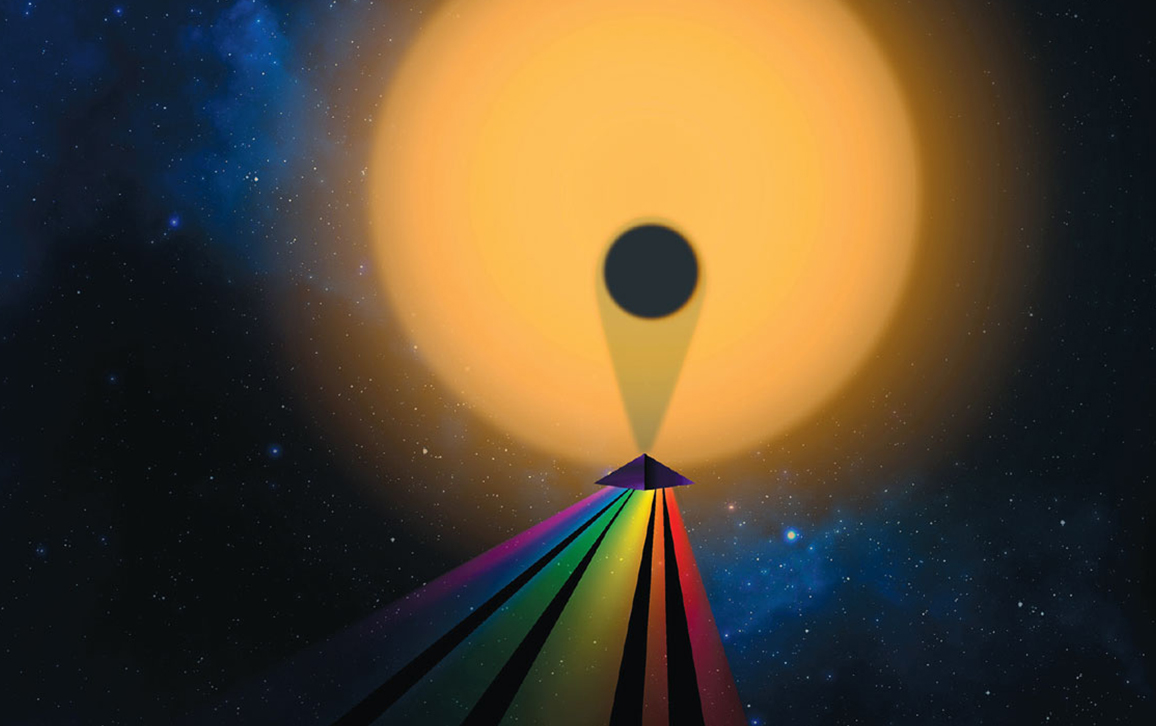

Short of mastering interstellar travel, our only means of probing the conditions on exoplanets is via remote sensing: deciphering the color of light from a distant exoplanet. These data offer us clues about an exoplanetary atmosphere’s formation history and surface conditions. In the short term, studying exoplanetary atmospheres is the only way for us to detect atoms and molecules in an exoplanet without actually traveling light years to get there.

This shift from the detection of exoplanets to the characterization of their chemical properties is an inexorable transition that is occurring within exoplanet science (see “The Study of Climate on Alien Worlds,” July–August 2012). The Kepler space telescope firmly established the ubiquity of exoplanets. Unfortunately, the vast majority of the exoplanets that Kepler discovered are too far away for astronomers to study their atmospheres. Nevertheless, the Kepler space telescope inspired the next generation of exoplanet-hunting space telescopes (see “The Next Great Exoplanet Hunt,” May–June 2015). Of these, the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) is fully operational and reporting discoveries of exoplanets orbiting the nearest, brightest stars. The Characterizing Exoplanet Satellite (CHEOPS) launched in December 2019; the cover of the telescope opened on January 29, and the telescope is currently in its commissioning phase.

Christine Daniloff / MIT, Julien de Wit

The nearby “golden target” stars and their transiting worlds are key for the next phase of exoplanet science. The objective is not only to perform surveys of the bulk properties (such as size or mass) of exoplanets but also to construct a catalog of their atmospheric properties. Astronomers hope the giant space telescopes equipped with state-of-the-art spectrographs will reveal these properties in the near future with the James Webb Space Telescope (see Perspective, March–April 2017) and perhaps in the distant future with proposed missions such as LUVOIR (see Perspective, September–October 2018).

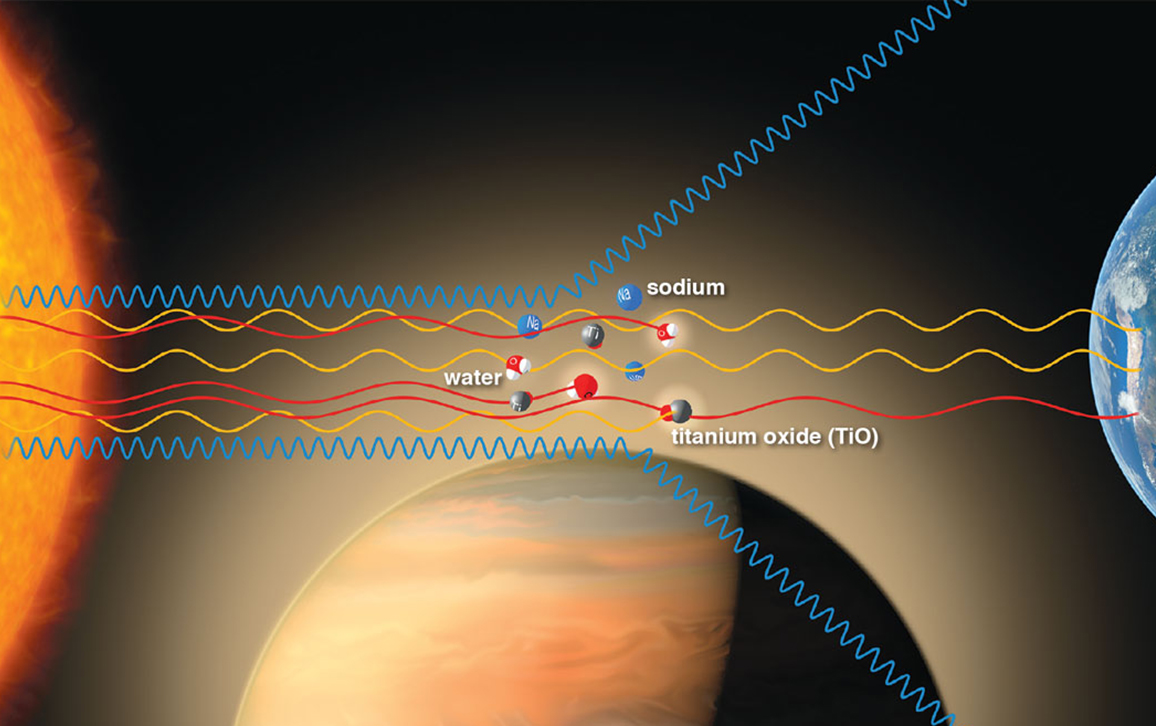

From our vantage point on Earth, some fraction of stars will have exoplanets residing in nearly edge-on orbits with respect to us. As the orbiting exoplanets obscure a part of their stars, a tiny dip occurs in light from the system; this process is known as a transit. If the exoplanet possesses an atmosphere, the depth of the transit varies with the color of the light (wavelength). This variation happens because atoms and molecules absorb light to different degrees depending on their color, which is quantified by a measurement known as the cross section. Researchers obtain these cross sections by performing quantum mechanical calculations on computer and laboratory measurements.

A thought experiment illustrates this mapping: Consider an exoplanet with an atmosphere that consists purely of gaseous water. At wavelengths where water is opaque to light, the size of the exoplanet—and thus its transit depth—will appear slightly larger. Conversely, at wavelengths where water is transparent to light, the exoplanet will appear comparatively smaller. For example, water absorbs more light at around 1.4 micrometers—in the near-infrared range of wavelengths. This principle guides astronomers who use the Wide Field Camera 3 (WFC3) on board the Hubble Space Telescope to probe exoplanets for water.

This general principle underlies the technique of transmission spectroscopy and may be used to search for any atom or molecule as long as we have knowledge of its cross section. The change in apparent size is a powerful tool, but it amounts to no more than a few percent change in a signal that is already tiny, which makes it a challenging measurement. The signal is maximized when researchers use transmission spectroscopy to scan very strong spectral lines of atoms and molecules, called resonant lines. A famous example of resonant lines are the Fraunhofer D-lines of the sodium atom (which absorb yellow light visible to the human eye), named after the German physicist Joseph von Fraunhofer, who studied them.

In a pioneering paper published in the Astrophysical Journal in 2000, Sara Seager of Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Dimitar Sasselov of Harvard University predicted that the sodium atom, which strongly absorbs light in the visible range of wavelengths, would be easily detected via transmission spectroscopy. (See "What's Next for Finding Other Earth-Like Worlds?" in the September–October 2018 issue.) Two years later, David Charbonneau of Harvard University and his collaborators reported the detection of sodium in the gas-giant exoplanet HD 209458b. Seager and Sasselov also predicted the detectability of helium in the near-infrared, but its discovery was not confirmed until 2018 by independent teams of astronomers. Since its first discovery in 2002, the detection of sodium in transiting exoplanets has become routine using ground-based telescopes equipped with state-of-the-art spectrographs such as the High Accuracy Radial Velocity Planet Searcher (HARPS) on the 3.6-meter telescope at La Silla Observatory in Chile. Sodium was a great test case, even though it is not a biosignature. Once it was clear that transmission spectroscopy could be used to detect sodium, it opened the floodgates to finding other atmospheric gases this way.

Transmission spectroscopy has been demonstrated to work for several species of atoms and molecules, including water, carbon monoxide, methane, potassium, iron, and titanium. These discoveries tend to be made in large, gas-giant exoplanets not unlike Jupiter in our Solar System—except that their atmospheric temperatures tend to be 1,000 kelvins or higher. Hydrogen and helium dominate the atmospheres of these exoplanets, implying a fluffy atmosphere with large variations in the spectral features of atoms and molecules. Trace molecules such as water, present at one part in a thousand or less, are detectable in such hot, fluffy atmospheres. Because these measurements are so challenging to make, transmission spectra obtained using the Hubble Space Telescopes tend to consist of about a dozen data points—landing us firmly in the regime of sparse data. Smaller, cooler exoplanets that might resemble Earth are out of Hubble’s reach.

Obtaining hard-earned data from a space telescope is only the first step; fully appreciating the information encoded within the data is the next step. The interpretation of sparse data requires understanding and shrewdly applying the tools of statistics. Instead of receiving a single answer from interpreting the data, researchers obtain a range or distribution of answers expressed as probabilities. The concept of what a probability means depends on the statistician’s school of thought. Frequentists view probabilities as the number of times an event occurs if one could perform an infinite number of equally probable trials—theoretical ideals that are difficult to reconcile with actual practice. Bayesians, on the other hand, regard probabilities as measuring degrees of belief about a hypothesis.

In a 2008 review article, Roberto Trotta of Imperial College London makes the case for the Bayesian school of thought: “The discovery zone for new physics is when a potentially new effect is seen at the 3- to 4-sigma level. This is when tantalizing suggestion for an effect starts to accumulate, but there is no firm evidence yet. In this potential discovery region, a careful application of statistics can make the difference between claiming or missing a new discovery.” In other words, a careful application of Bayesian inference allows us to consider scientific results at the bleeding edge of research.

In the classical approach, a researcher makes a theoretical prediction for what the transmission spectrum looks like and then compares it to data. A “goodness of fit” criterion is evaluated, and the theoretician declares victory or failure of the model’s ability to match data (or be decisively confronted and ruled out by it). When dealing with sparse data, one needs to execute a mental shift: There are now families of theoretical models that may be consistent with the data to different degrees. In the context of decoding transmission spectra, one has to ask, What is the appropriate level of sophistication that is warranted in the theoretical model, given the quality of the data? It is essentially the application of Occam’s razor: Given a family of models, the least sophisticated one is preferred—at least until better data are available to overturn the hypothesis.

In a less abstract example, is the water molecule alone sufficient to explain the bumps and dips in the transmission spectrum? Or are other molecules such as ammonia present and needed to explain the patterns observed? Are there sharp changes in temperature that need to be accounted for? Are clouds present that are made up of exotic particles (for example, olivine)? The theoretician proceeds to calculate transmission spectra for all these possibilities and compares them to the data. Associated with each model is a quantity known as the Bayesian evidence. By comparing the Bayesian evidences between models, one may identify the family of models that is consistent with—but not necessarily proven correct by—the data. One may also identify models that the data rule out. This Bayesian model comparison informs us that water is confidently detected in the dozens of transmission spectra the Hubble Space Telescope has measured so far, with claims for other molecules generally requiring further corroboration from future space telescopes.

ESO/M. Kornmesser

By measuring water abundances from a large sample of exoplanets, astronomers hope to uncover trends in the sample that offer hints on how they formed. Researchers may use hydrogen-dominated, gas-giant exoplanets in such an experiment, because to a good approximation their atmospheric compositions resemble those of their host stars. Variations in the abundances of molecules within their atmospheres arise when they form in different locations within a primordial disk of dust and gas around their stars. Farther away from the star, the temperatures drop and molecules freeze into their solid phases. These locations around the star are known as ice lines (or snow lines). The water ice line occurs first, followed by that of carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide. As these molecules freeze, they become unavailable for incorporating into the atmosphere of the gas-giant exoplanet. It is then not hard to imagine that, depending on where the exoplanet formed relative to these ice lines, the oxygen content of the gaseous atmosphere will vary. If most of the oxygen is subsequently locked up in gaseous water, then measuring the abundance of water will provide a direct constraint on the oxygen content and hence the formation history of the exoplanet. Several caveats, which are at the forefront of active research, complicate this narrative, including the possibility that some of the oxygen may be sequestered by other molecules that do not announce their presence in the transmission spectrum.

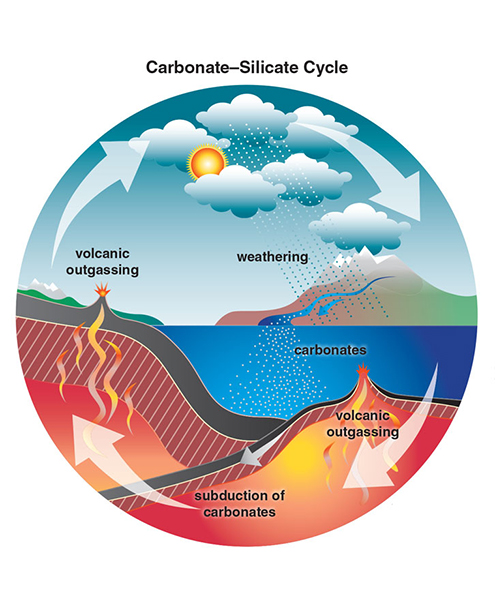

For rocky exoplanets, it will be much tougher to infer their formation history from their atmospheric compositions. Gas-giant exoplanets have primary atmospheres that reflect their history of formation. Rocky exoplanets are expected to have secondary atmospheres that are controlled by geochemical cycles. For example, the carbonate-silicate cycle or long-term carbon cycle on Earth regulates the amount of carbon dioxide—a potent greenhouse gas—present in the terrestrial atmosphere.

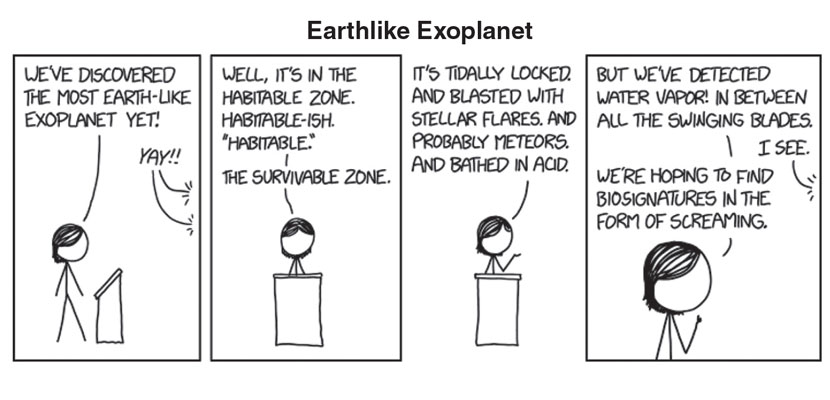

www.xkcd.com / CC-BY-205

With rocky exoplanets that may resemble Earth, the scientific question is rather one of whether biology is present on their surfaces. Gases that robustly indicate the presence of biology are known as biosignatures gases. Such gases would need to be produced in large enough amounts that they would imprint their signatures on the transmission spectrum of the exoplanet. They would have to be stable over geological timescales, because if they exist for only a fleeting instance in the history of the exoplanet, astronomers would have little chance to detect them in a sample of rocky exoplanets. A major source of confusion is the ability of geochemical cycles to produce the same gases, such as carbon dioxide and methane, without the participation of biology—thus creating geological false positives that mimic biosignatures. Seager calls these Type I biosignatures. Biosignatures that cannot be mimicked by geology are Type III biosignatures, but they are expected to be present in vanishing amounts. On Earth, a Type III biosignature is dimethylsulfide, which is produced by tiny plants in the ocean and present at less than one part in a billion in the atmosphere of Earth. Unfortunately, biosignatures are expected to be beyond the reach of even the James Webb Space Telescope.

From the viewpoint of decoding the transmission spectrum, one would either have to collect a rich inventory of Type I gases (such as methane and ammonia) and assess the probability of their presence being due to biology, or one would have to attempt to dig out the faint signature of a Type III biosignature among a forest of spectral lines from other, abiotic molecules. This grand challenge faces the next generation of exoatmospheric scientists as giant space telescopes with the sensitivity and wavelength coverage to make these measurements come online.

Illustration by Jenny Leibundgut.

Other challenges await the measurement and interpretation of transmission spectra of rocky Earth-sized exoplanets. If the atmosphere is nitrogen-dominated (like Earth’s), then variations in the spectral features of atoms and molecules shrink by a factor of 10, making them much harder to detect. Some of these signals may be buried in the noise produced in the infrared detectors and by the mode of telescope operation. Furthermore, as the size of the exoplanet shrinks relative to its star, contamination by imperfections on the stellar surface, such as star spots, become an increasing concern. Refraction, the bending of light rays because of variations in density, becomes an effect that cannot be ignored in transmission spectroscopy. All these factors culminate in the opinion, held by a part of the exoplanet community (including myself), that although transmission spectroscopy is useful for studying gas giants orbiting Sun-like stars (or Earth-sized exoplanets orbiting small red-dwarf stars such as TRAPPIST-1), it is probably not the optimal technique for studying the “Earth twins”—Earth-sized exoplanets orbiting Sun-like stars. In the next few years, the community’s best shot at understanding the habitability of Earth-sized exoplanets will be to apply transmission spectroscopy to those orbiting small red-dwarf stars.

No photons from an exoplanet are measured during transmission spectroscopy. Rather, current techniques rely on measuring the size of the shadow the exoplanet and its atmosphere cast on its star. The only light that enters the detectors of the telescope is from the star. The direct measurement of infrared photons from the exoplanet is immensely challenging, because the star outshines the exoplanet by a factor of a million to a billion, depending on the color of light being measured. Direct imaging relies on sophisticated techniques, implemented both via hardware and software, to suppress starlight. It is the technique that the proposed LUVOIR space telescope, pitched as a successor to both the Hubble and James Webb space telescopes, will use to perform a census of Earth-like exoplanets and hunt for biosignatures in our cosmic neighborhood.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.