What's in a Shape?

By Alexey A. Petrov

How far an electron veers from spherical has implications for the existence of other, theoretical particles and our understanding of the structure of the universe.

How far an electron veers from spherical has implications for the existence of other, theoretical particles and our understanding of the structure of the universe.

What is the shape of an electron? If you recall pictures from your high school science books, the answer seems quite clear: an electron is a small ball of negative charge that is smaller than an atom. This description, however, is quite far from the truth.

The electron is commonly known as one of the main components of atoms making up the world around us. It is the electrons surrounding the nucleus of every atom that determine how chemical reactions proceed. Their uses in industry are abundant: from electronics and welding, to imaging and advanced particle accelerators. Recently, a physics experiment called Advanced Cold Molecule Electron EDM (ACME) put an electron on the center stage of scientific inquiry. The question that the ACME collaboration tried to address was deceptively simple: What is the shape of an electron?

As far as physicists currently know, electrons have no internal structure—and thus no shape in the classical meaning of this word. In the modern language of particle physics, which tackles the behavior of objects smaller than an atomic nucleus, the fundamental blocks of matter are continuous fluidlike substances known as quantum fields that permeate the whole space around us. In this language, an electron is perceived as a quantum, or a particle, of the “electron field.” Knowing this, does it even make sense to talk about an electron’s shape if we cannot see it directly in a microscope—or with any other optical device, for that matter?

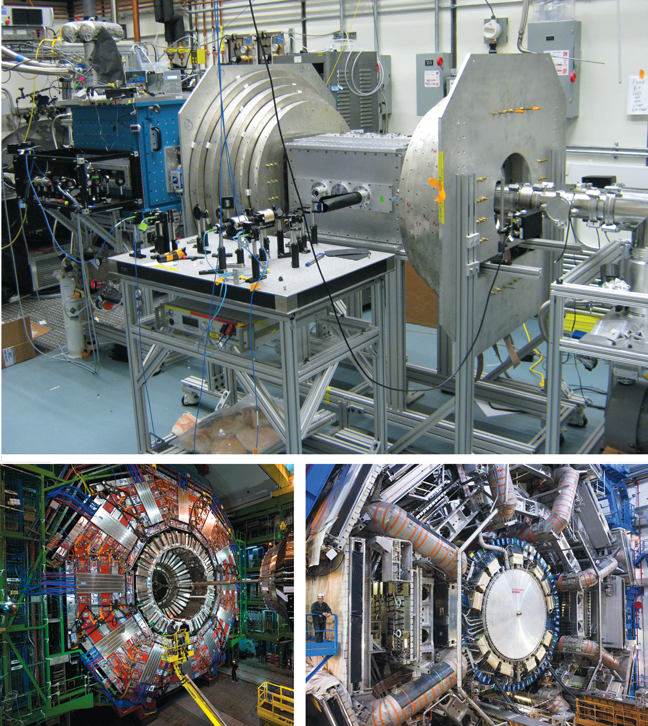

Harvard Department of Physics, CC BY-NC-SA; Maximilien Brice/© CERN; ATLAS Experiment © 2014 CERN

To answer this question we must adapt our definition of shape so it can be used at incredibly small distances, or, in other words, in the realm of quantum physics. Seeing different shapes in our macroscopic world really means detecting, with our eyes, the rays of light bouncing off different objects around us.

Simply put, we define shapes by seeing how objects react when we shine light onto them. Although this might be a weird way to think about shapes, it becomes very useful in the subatomic world of quantum particles. It gives us a way to define an electron’s properties such that they mimic how we describe shapes in the classical world.

What replaces the concept of shape in the micro world? Because light is nothing but a combination of oscillating electric and magnetic fields, it would be useful to define the quantum properties of an electron that carry information about how it responds to applied electric and magnetic fields.

As an example, consider the simplest property of an electron: its electric charge. It describes the force—and ultimately, the acceleration the electron would experience—if it were placed in some external electric field. A similar reaction would be expected from a negatively charged marble—hence the “charged ball” analogy of an electron that is in elementary physics books. This property of an electron—its charge—survives in the quantum world.

If we shine light onto the electron, some of the light could bounce off the virtual particles in the cloud instead of the electron itself.

Likewise, another “surviving” property of an electron is called the magnetic dipole moment. It tells us how an electron would react to a magnetic field. In this respect, an electron behaves just like a tiny bar magnet, trying to orient itself along the direction of the magnetic field. Although it is important to remember not to take those analogies too far, they do help us see why physicists are interested in measuring those quantum properties as accurately as possible.

What quantum property describes the electron’s shape? There are, in fact, several of them. The simplest—and the most useful for physicists—is the one called the electric dipole moment, abbreviated as EDM.

In classical physics, EDM arises when there is a spatial separation of charges. An electrically charged sphere, which has no separation of charges, has an EDM of zero. But imagine a dumbbell whose weights are oppositely charged, with one side positive and the other negative. In the macroscopic world, this dumbbell would have a nonzero electric dipole moment. If the shape of an object reflects the distribution of its electric charge, it would also imply that the object’s shape would have to be different from spherical. Thus, naively, the EDM would quantify the “dumbbellness” of a macroscopic object.

The story of EDM, however, is very different in the quantum world. There the vacuum around an electron is not empty and still. Rather, it is populated by various subatomic particles zapping into virtual existence for short periods of time.

B.R. O’Leary/Physics.org/Yale University

These virtual particles form a “cloud” around an electron. If we shine light onto the electron, some of the light could bounce off the virtual particles in the cloud instead of the electron itself.

This result would change the numerical values of the electron’s charge and magnetic and electric dipole moments. Performing very accurate measurements of those quantum properties would tell us how these elusive virtual particles behave when they interact with the electron and whether they alter the electron’s EDM.

Most intriguing, among those virtual particles there could be new, unknown species of particles that we have not yet encountered. To see their effect on the electron’s electric dipole moment, we need to compare the result of the measurement to theoretical predictions of the size of the EDM calculated in the currently accepted theory of the universe, which is called the Standard Model.

So far, the Standard Model has accurately described all laboratory measurements that have ever been performed. Yet, it is unable to address many of the most fundamental questions, such as why matter dominates over antimatter throughout the universe. The Standard Model makes a prediction for the electron’s EDM, too: it requires it to be so small that ACME would have had no chance of measuring it. But what would have happened if ACME actually detected a nonzero value for the electric dipole moment of the electron?

Theoretical models have been proposed that fix shortcomings of the Standard Model, predicting the existence of new heavy particles. These models may fill in the gaps in our understanding of the universe. To verify such models, we need to prove the existence of those new heavy particles. This could be done through large experiments, such as those at the international Large Hadron Collider (LHC) by directly producing new particles in high-energy collisions.

Maximilien Brice/© CERN

Alternatively, we could see how those new particles alter the charge distribution in the “cloud” and their effect on an electron’s EDM. Thus, unambiguous observation of electron’s dipole moment in the ACME experiment would prove that new particles are in fact present. That was the goal of the ACME experiment.

This goal is the reason a recent research paper by the ACME collaboration in the journal Nature about the electron caught my attention. Theorists such as myself use the results of the measurements of the electron’s EDM—along with other measurements of properties of other elementary particles—to help identify the new particles and make predictions of how they can be better studied. This theoretical work is done to clarify the role of such particles in our current understanding of the universe.

The fact that an electron's electric dipole moment was not observed actually rules out the existence of heavy new particles that could have been easiest to detect at the LHC.

What should be done to measure the electric dipole moment? We need to find a source of very strong electric field to test an electron’s reaction. One possible source of such fields can be found inside molecules such as thorium monoxide. This is the molecule that ACME used in their experiment. Shining carefully tuned lasers at these molecules, a reading of an electron’s EDM could be obtained, provided it is not too small.

However, as it turned out, it is too small. Physicists of the ACME collaboration did not observe the EDM—which suggests that its value is too small for their experimental apparatus to detect. This fact has important implications for our understanding of what we could expect from the LHC experiments in the future.

Interestingly, the fact that the ACME collaboration did not observe an EDM actually rules out the existence of heavy new particles that could have been easiest to detect at the LHC. This result is remarkable for a tabletop-sized experiment that affects both how we would plan direct searches for new particles at the giant LHC and how we construct theories that describe nature. It is quite amazing that studying something as small as an electron could tell us a lot about the universe.

This article is adapted from one that appeared on The Conversation,.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.