Cuban and American Physics

By Sandra J. Ackerman

As the political divide between the two countries begins to narrow, enthusiasm for scientific collaboration is running high on both sides.

As the political divide between the two countries begins to narrow, enthusiasm for scientific collaboration is running high on both sides.

DOI: 10.1511/2016.120.142

Just a few weeks ago, a landmark meeting of Cubans and Americans laid the foundation for a new era of cooperation between the two nations. No, not Barack Obama’s trip to Havana—although the first state visit by an American president in more than 80 years was certainly newsworthy in its own right—but a much smaller convocation that went almost unnoticed by the press: Several members of the Cuban Physical Society got together with emissaries from the American Physical Society.

At this gathering, hosted by María Sánchez-Colina, president of the Cuban Physical Society, the eight physicists present traded overviews of their organizations and discussed ways of deepening their association in the future. “The meeting was very friendly, and I think it was a first step in gaining momentum for exchanges in the field of physics between Cuba and the United States,” says Ernesto Altshuler, professor of physics at the University of Havana and editor of the Cuban Journal of Physics (below). “One premise was clear to all the participants even before we began: In spite of the huge differences in size between the American Physical Society and the Cuban Physical Society, we would respect each other and collaborate with each other. We would respect diversity, so to speak.”

Such collegial exchanges are not unusual for Cuban physicists. For example, for decades they have enjoyed mutually fruitful scientific exchanges with the Abdus Salam International Centre for Theoretical Physics (ICTP), an organization housed in Trieste, Italy. The ICTP has sponsored courses and workshops in Cuba, as well as the attendance of Cuban scientists at international meetings in Italy.

By contrast, decades of estrangement with the United States have left their mark, in that many practical challenges still clutter the path of free scientific exchange. Although travel from Cuba to the United States is now a fairly straightforward matter, travel to Cuba for American citizens is still “not trivial,” says Altshuler. He adds, however, “Things are now changing so fast in that respect that I can hardly follow them!”

The two representatives from the American Physical Society—Laura Greene, the society’s president-elect, and Amy Flatten, its director of international relations—had already planned to attend an international workshop on science teaching in Havana, so it was natural that when they convened with colleagues in the Cuban Physical Society the talk would turn first to increasing the exchange of students, researchers, and professors. Cuban physicists are eager to host U.S. professors who can give seminars and short courses. “We’re also having a first look at the possibility of future donations of scientific equipment—even simple devices such as standard digital cameras—to Cuba from the States, because since the early 1990s, with a lack of support from the former Soviet Union and some other countries, combined with the embargo, our material support was going really far down,” Altshuler explains.

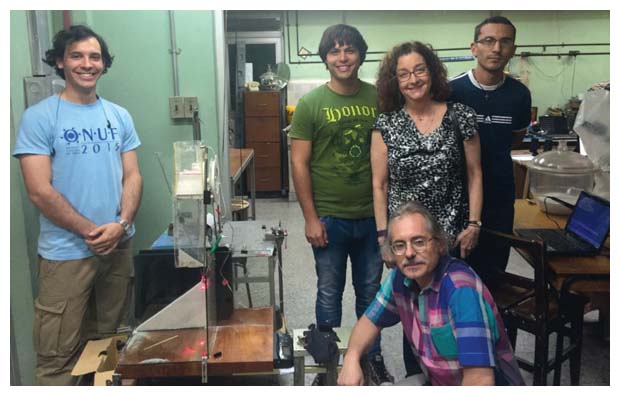

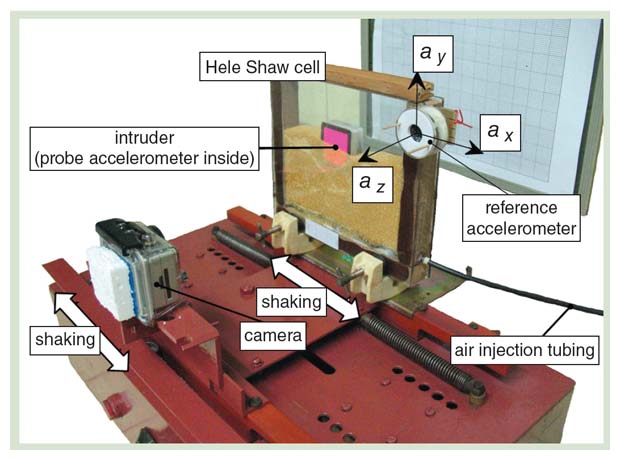

For his part, Altshuler has survived as a physicist by devising simple experiments from materials that are readily available. One creative exercise of his faculties led him to study the physical principles governing the behavior of panicked ants; another (illustrated below) allows him to investigate the dynamics of granular matter. Although he considers himself fortunate to do part of his work in areas of physics in which the ability to improvise can be fruitful, he worries about the sustainability of research in other areas—those in which difficult-to-obtain equipment (for instance, an electron microscope or an x-ray diffractometer) may be essential for progress. For many years, the embargo has made it difficult—not to say impossible—to sell or donate to Cuba any scientific equipment unless the donating country can stipulate that the American-made parts of the equipment constitute less than a certain percentage of the whole instrument.

If the embargo has largely prevented an influx of the latest scientific equipment into Cuban research facilities, it has been less successful at the level of individual scientists. As far back as 2000, Altshuler held a postdoctoral position at the Texas Center for Superconductivity; he visited Argonne National Lab and the Rockefeller University last February and is planning a similar trip early in 2017. And some American scientists have come to Cuba: At the University of Havana, the physics department alone has hosted visits from Leon Lederman, Murray Gell-Mann, Walter Kohn, and Leo Kadanoff, among others; most recently, Greene gave a physics colloquium at the university. A workshop on complex matter physics, organized in 2012 by Altshuler and his Norwegian colleague Jon Otto Fossum, brought eminent physicists to Havana from 10 different countries, including several invited speakers from the United States. According to Altshuler, “There has been an exchange, but not at the level we have had with Europe or Mexico or Brazil.” Certain fields, such as medicine and the biomedical sciences, have seen a higher level of exchange in the past decade because of important mutual interests—in particular, the need to confront rapidly spreading diseases.

However, says Altshuler, “Now, after the first contacts between Obama and Raul Castro and others, definitely there is a lot of expectation—and there are lots of new contacts, which have to mature. In my own experience, I am receiving two or three proposals every month from U.S. scientists who want to come to Cuba, who want to co-organize a scientific meeting in Cuba, and more.” Altshuler is inclined to think that at this point, so early in the rapprochement between the two countries, it may be too soon to say how profoundly the new political relationship may change the research environment across the Florida Straits. He does observe, however, that “the first derivative of the system is very high.”

When asked to name the greatest asset that he and his Cuban colleagues can offer new collaborators, Altshuler doesn’t hesitate: “The greatest asset is enthusiasm!” He is referring not only to his own energetic curiosity, but also to the enthusiasm he foresees among young researchers and students. Moreover, physicists in Cuba have a highly developed ability to get results out of small resources. For example, Osvaldo de Melo and Roberto Cao, also at the University of Havana, have been creating nanostructures for decades through the efficient use of extremely basic equipment.

In 2004, when the thawing of American–Cuban relations was only a distant hope, two American Scientist editors visited Cuba and spoke with a number of scientists there. Sergio Pastrana, who at that time oversaw international relations for the Cuban Academy of Sciences, shared his vision for the future: “Eventually, Cuba could live off knowledge instead of sugar.” Twelve years afterward, when Altshuler is asked to lay out his own vision, he focuses on the effective use of Cuba’s human resources: “I would say that medical and biotechnological services and products have been reasonably successful already, in spite of the embargo. But I feel that the country needs to strengthen the connection between industry and other disciplines: mathematics, computer science—and physics, of course.” Ultimately, Altshuler hopes to see Cuba supported by “a robust web of resources, in which knowledge should be like the glue linking all of them.”

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.