This Article From Issue

September-October 2025

Volume 113, Number 5

Page 311

AMAZING WORLDS OF SCIENCE FICTION AND SCIENCE FACT. Keith Cooper. 224 pp. University of Chicago Press, 2025. $22.50.

When Star Trek first aired in 1966, it posited a universe bursting with planetary possibilities—a bold move at a time before anyone knew of a single planet beyond our Solar System.

Nearly 60 years later, we now know for sure that we live in such a universe. Astronomers have discovered roughly 6,000 exoplanets, worlds orbiting other stars. Statistically speaking, our galaxy alone must be home to hundreds of billions of planets, many of which are bound to resemble Earth in their size, mass, and temperature. In other words, there really is a strange new world to visit every week—if only we had warp drive.

Shisma/Wikimedia Commons

In the absence of physics-defying, faster-than-light propulsion, we have two tools of exploration at our disposal: astronomy and imagination. Keith Cooper’s new book, Amazing Worlds of Science Fiction and Science Fact, investigates how these two tools are intertwined in our understanding of our planet-filled cosmos. Science and science fiction exist in a symbiotic relationship: Cosmic discoveries open new realms for storytelling, and boundary-pushing narratives inspire researchers to probe ever further and imagine realities that just might be crazy enough to be true.

Amazing Worlds is structured around chapters dedicated to different classes of planets depicted in science fiction, such as desert worlds, ocean worlds, ice worlds, worlds that orbit more than one star, and worlds with no sun at all. Cooper picks notable examples of each kind of planet, using them as vehicles of the imagination to provide an accessible way to understand the basic principles of planetary environments. Those principles furnish readers with a foundation for exploring more abstract studies within exoplanet science.

In his chapter “Lands of Sand,” Cooper uses the planet Arrakis from Frank Herbert’s Dune novels and their multiple on-screen adaptations to discuss the processes that influence a planet’s climate, such as the greenhouse effect, the ice–albedo feedback loop, and the carbonate–silicate weathering cycle. He then uses these concepts to explain how planetary scientist Yutaka Abe at the University of Tokyo and his colleagues have modeled the climates of Arrakis-like worlds. The models constructed by Abe and his colleagues demonstrate that drier worlds should maintain their habitability under a wider range of conditions than ocean-covered worlds. This counterintuitive finding means that “planets like Arrakis may greatly outnumber planets like Earth,” writes Cooper, before providing an informative sidebar about the great lengths that life must go to, in order to adapt to harsh desert environments. He concludes the chapter with a prescient reminder: “We’re lucky to have Earth, and we should never take her for granted.”

Indeed, for all our efforts, we have yet to find another truly Earthlike planet, though scientists are currently working on technologies that might enable that momentous discovery. (See “Earth 2.0 Could Be Just Around the Corner,” May–June 2024.) Instead, we have populated our scientific catalog of exoplanets with true anomalies. Gassy worlds lighter than cotton candy, like the “super-puff” Kepler-51. Scathing oceans of lava, such as CoRoT-7b, whose surface could be hotter than 1,000 degrees Celsius. Skies with clouds of gemstones, the natural precipitates in the atmospheres of worlds like WASP-121b. “No matter how bizarre planets are in science fiction, astronomical history has shown that the universe can throw at us planets even more bizarre than anything we could have dreamed of,” Cooper writes. These discoveries, in turn, populate the skies of science fiction with even more fantastical settings, allowing storytellers to draw on the ever-expanding science of exoplanets.

For example, Cooper explores how author Charlie Jane Anders was inspired by recent discoveries of tidally locked exoplanets—worlds where one hemisphere experiences perpetual day, and the other, endless night. Tidal locking is common for worlds that orbit close to their host stars, resulting in scores of exoplanets without our familiar sunrises and sunsets. How would one know when to sleep and when to be awake? Anders populates her fictional tidally locked planet with one society that imposes a strictly regulated curfew, and another that embraces the chaos of timelessness. “I really just started obsessing about once you confront the idea of maintaining sleep schedules, how far are you willing to go into social control?” she tells Cooper. Cultural contemplation has been part of science fiction since its inception. By transporting us far from the here and now, it invites us to critique our own society from a different angle. Now, thanks to the exotic exoplanets astronomers have found, science fiction has a plethora of strange new vantage points to play with.

Science fiction typically reflects not only the current cultural zeitgeist, but it also takes a freeze-frame of our current scientific knowledge. Despite all of our searching, we have not yet confirmed conditions conducive to life on any exoplanet, much less irrefutable evidence of life itself. Hence, contemporary science fiction is adapting to the idea that intelligent life might be rare in the universe.

Some of the most striking parts of Amazing Worlds come through the inclusion of Emma Puranen, an astrobiologist, historian, and ethicist who studies the portrayal of exoplanets in science fiction over time. “Puranen’s research suggests that planets that are home to indigenous technological species are not written about as frequently as before,” Cooper writes. He continues,

When exoplanets existed only in our imagination, it was easy to conjure up fictional societies to inhabit them because storytellers could make those fictional exoplanets as hospitable as they wanted. Now that we know of thousands of exoplanets, none of which, at the time of writing, are known to be habitable like Earth, it’s harder to picture worlds upon which societies—either human or alien—could thrive.

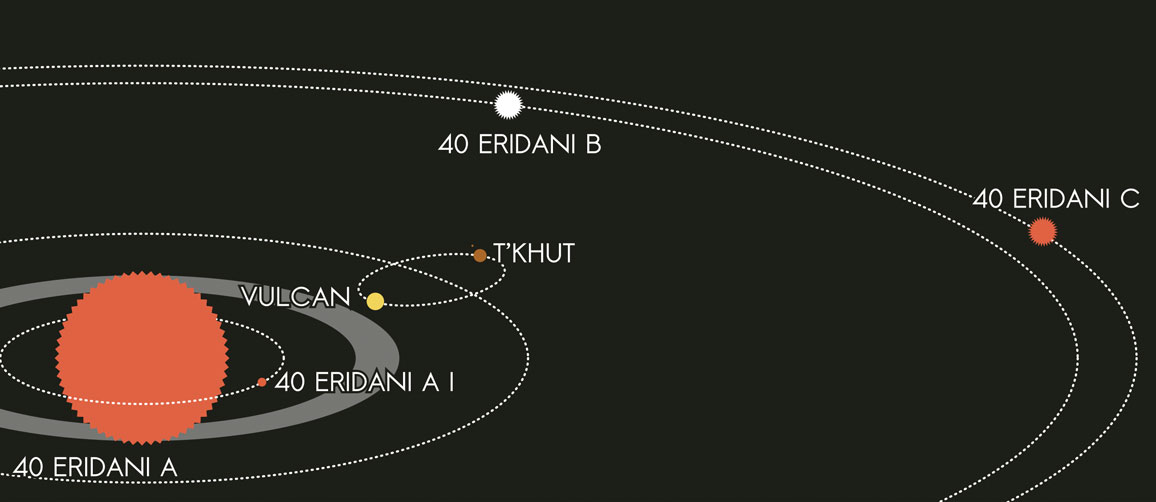

The influence flows both ways. Exoplanet researchers draw on ideas from fiction in choosing what to look for. A fun example is the search for a planet around 40 Eridani A, the home star of the fictional planet Vulcan in Star Trek. Scientists looked with special interest there, and in 2018 thought they had found a planet. But newer studies suggest the planet was an illusion—an artifact in the data likely due to star spots.

Cooper further illustrates how science fiction propels scientists such as Amaury Triaud, an astronomer with more than a hundred exoplanet discoveries to his name. Triaud was involved in the discovery of the TRAPPIST-1 system, for instance, which contains seven roughly Earth-sized exoplanets orbiting a dim, red star some 40 light-years away. Early in Triaud’s career, Swiss science fiction writer Laurence Suhner consulted Triaud on the science of circumbinary planets for her QuanTika trilogy. “Funnily enough, I wasn’t working on circumbinary planets at the time, and now I am,” Triaud tells Cooper. “In so many strange ways, science fiction becomes reality!” Planets with multiple suns are a staple of science fiction. Now, thanks in no small part to Triaud and his colleagues, researchers are actually finding them, learning which of the imagined possibilities align with observed reality.

Through its examination of planets built for entertainment, Amazing Worlds offers an engaging survey of the latest results in exoplanetary science. And through his conversations with scientists and writers, Cooper demonstrates how entwined imagination and ingenuity are at the forefront of astronomical understanding. If there’s anything that exoplanets have taught us, it’s that we must expect the unexpected. And if there’s anything that science fiction can do for science, it’s to help us do just that.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.