This Article From Issue

January-February 2026

Volume 114, Number 1

Page 13

In this roundup, associate editor Nicholas Gerbis summarizes notable recent developments in scientific research, selected from reports compiled in the free electronic newsletter Sigma Xi SmartBrief.

Extrasolar Ejection Observed

NASA/CXC/INAF/Argiroffi, C. et al./S. Wiessinger

Scientists have detected the first direct evidence of a large discharge of plasma called a coronal mass ejection (CME) from a star other than our Sun. The M-dwarf star StKM 1-1262 lies 130 light-years away, is half as massive as our home star, and rotates about 20 times faster. Astronomers are interested in CMEs in part because they can erode the atmospheres of potentially habitable exoplanets, especially around M-dwarfs, which make up around three-quarters of the Milky Way and are the stars most likely to have multiple rocky exoplanets orbiting within their habitable “Goldilocks” zones. But these planets must orbit close to these small, cool, and dim stars in order to stay neither too hot nor too cold to support liquid water and, by extension, life. Such close orbits could render these worlds especially vulnerable to CMEs from M-dwarfs, which have magnetic fields hundreds of times as powerful as our Sun’s and can therefore potentially blast out far stronger CMEs. Previous studies inferred CME occurrences by detecting indirect signs of stellar eruptions, signals that could not definitively show that plasma had left the star and been ejected into space. This time, the team, led by scientists from ASTRON, the Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy, detected radio-wave data consistent with signals that accompany the kinds of shocks that blast plasma free from a star’s magnetosphere and into space. This result now means astronomers are using direct information and not extrapolating solar data to stars with vastly different physical parameters.

Callingham, J. R., et al. 2025. Radio burst from a stellar coronal mass ejection. Nature 647:603−607.

Brainy Sea Urchins

Bethany Weeks/Flickr.com

A new genetic and microscopic analysis suggests that young adult sea urchins might be “all brain”—genetically speaking, at least. The study of purple sea urchins (Paracentrotus lividus), led by scientists at the Anton Dohrn Zoological Station in Naples, Italy, challenges longstanding notions about the evolution of nervous systems and body plans, particularly among animals such as echinoderms, which don’t have brains or even obvious centralized nervous systems. Using single-nucleus RNA sequencing to detect genetic activity in each cell nucleus, the team discovered that genes akin to those found in vertebrate brains are present throughout the urchin’s nervous system. Moreover, unlike the head−trunk−tail body plan common to many animals, the urchin’s body is like one big head, with its trunk-associated genes confined to its internal gut and vascular systems. The data also show unusual patterns of neural signaling. Unlike most animals, in which each neuron type uses a single neurotransmitter (serotonergic neurons produce serotonin, for example), P. lividus has neurons with more than one neurotransmitter signature. That multiplicity means that two neurons of the same broad type might have different, specialized functions. The findings, which the authors say likely apply to all sea urchins, suggest scientists should use their brains to rethink how body plans and nervous systems evolved—and to reevaluate what constitutes neurological sophistication.

Paganos, P., et al. 2025. Single-nucleus profiling highlights the all-brain echinoderm nervous system. Science Advances 11:eadx7753.

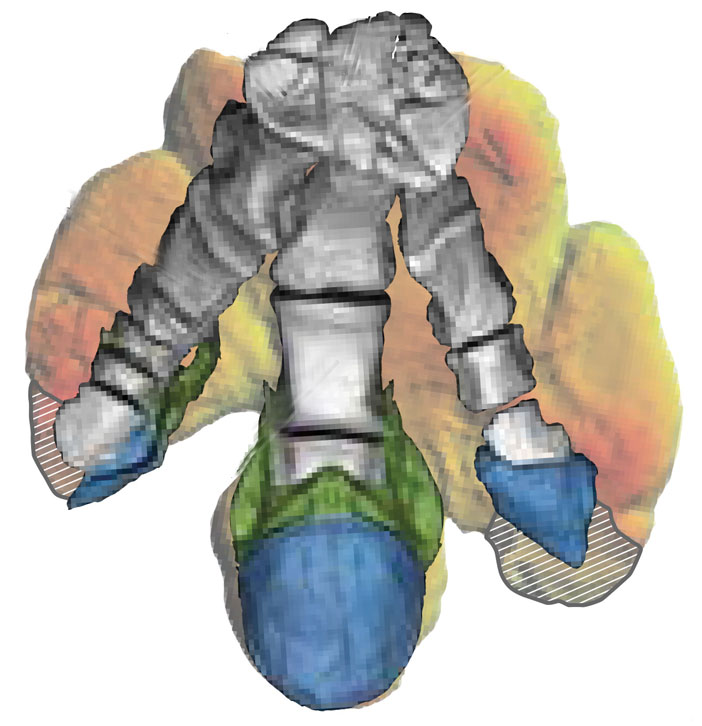

Hoofed Dinosaur Unearthed

Sereno et al. 2025.

For the first time, scientists have found evidence that some dinosaurs had hooves. Impressions of the broad, triangular, keratinous toe coverings of a duck-billed hadrosaur called Edmontosaurus annectens were preserved in a fine, intricate clay after the creature died sometime during the Late Cretaceous period around 66 million years ago. The discovery of hooves, a typically mammalian trait, on a large ancient reptile changes the longstanding image of dinosaurs sporting flat, clawed feet or soft pads, and could suggest different forms of locomotion and adaptation than were previously considered. In another first for the team, which was led by scientists at the University of Chicago, the type of clay mask preserving the details of the young adult E. annectens has never before been observed outside of an anoxic marine setting; the clay formed after the dinosaur had died, dried out, and was buried in wet, porous sediment. Within this covering, a layer of microbes on the decaying animal’s skin produced a slimy biofilm that electrostatically attracted tiny clay particles to cling to it, preserving fine details long after the organic matter had decayed away. Analysis of the specimen and others in the area suggests an explanation for why this east-central Wyoming site produces so many of what paleontologists call dinosaur “mummies”: The area was once a coastal floodplain that experienced seasonal wet-dry cycles and monsoons, and where land subsided quickly. This combination of factors dried out and rapidly buried dinosaur bodies, creating ideal conditions for fossilizing their soft tissues.

Sereno, P. C., et al. 2025. Duck-billed dinosaur fleshy midline and hooves reveal terrestrial clay-template “mummification.” Science. doi:10.1126/science.adw3536.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.