This Article From Issue

July-August 2019

Volume 107, Number 4

Page 207

In this roundup, managing editor Stacey Lutkoski summarizes notable recent developments in scientific research, selected from reports compiled in the free electronic newsletter Sigma Xi SmartBrief.

Minerals from Moon’s Mantle

China’s Chang’e-4 mission may have identified material from the Moon’s mantle. The Yutu-2 rover, which is exploring the Von Kármán crater on the far side of the Moon, identified two minerals that are not typical of the lunar surface: low-calcium pyroxene and olivine. The presence of these minerals bolsters the theory that the massive Aitken Basin at the Moon’s South Pole was created by an enormous impact that exposed the lunar mantle and made it possible to study the Moon’s deep history. If these minerals did originate in the mantle, they may provide information about the Earth’s geological state at the moment it collided with a protoplanet, creating the terrestrial debris from which the Moon was formed.

Wikimedia Commons

Li, C. et al. Chang’e-4 initial spectroscopic identification of lunar far-side mantle-derived materials. Nature 569:378–382 (May 15)

Drug Reactions Differ by Sex

Women are more likely than men to report adverse drug reactions. A team of pharmacologists analyzed reports of adverse drug reactions to the National Pharmacovigilance Centre in the Netherlands. Out of 2,483 distinct drug combinations that caused adverse reactions, 363 had a possibly relevant sex difference, and 322 of those cases were reported by women. The greatest numbers of adverse drug reactions were reported for thyroid medications and for antidepressants, and headaches and dizziness were the most common symptoms. As reported on our From the Staff blog, most biomedical and clinical research is conducted exclusively on male cells and subjects (“Eliminating Sex Bias in Biomedical and Clinical Research,” https://bit.ly/2FLSHZo). As a result, researchers do not know whether female cells and subjects react differently to drugs or treatments. The pharmacologists who conducted this study suggest that the results may lead to sex-specific prescribing or monitoring recommendations.

de Vries, S. T., et al. Sex differences in adverse drug reactions reported to the National Pharmacovigilance Centre in the Netherlands: An explorative observational study. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology doi:10.1111/bcp.13923 (April 2)

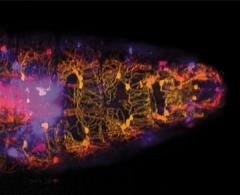

Neural Network Numerosity

An artificial neural network has spontaneously acquired number sense. Humans and animals have number sense, an innate ability to intuitively assess the number of objects they see in a set (the set’s numerosity). However, most artificial neural networks need to be taught number sense. A team of neurobiologists and neurotechnologists tested a biologically inspired model called a hierarchical convolution neural network to see whether it could acquire number sense from visual cues without direct programming. The researchers trained the artificial neural network to visually classify objects in a data set of approximately 1.2 million images. They then showed the network a series of black images with between 1 and 30 white dots and found that it could reliably categorize the images by the number of dots. These findings suggest that the neural mechanisms of vision are directly related to number sense.

Nasr, K., P. Viswanathan, and A. Nieder. Number detectors spontaneously emerge in a deep neural network designed for visual object recognition. Science Advances doi:10.1126/sciadv.aav7903 (May 8)

Promising Allergy Therapy

Preschoolers with peanut allergies may safely undergo oral immunotherapy, according to the authors of a recent study. The findings are notable because the daily doses were administered at home rather than in a controlled environment. Over a two-year period, a team of allergists and immunologists studied 270 children between the ages of nine months and five years who had peanut allergies. Caregivers administered daily doses of peanut protein, with biweekly visits to an allergist to increase the dosage. Ninety percent of the participants reached the maintenance phase, and out of 41,020 doses administered, epinephrine was required only 12 times. Previous studies had focused on older children and had shown higher rates of adverse affects. This report confirmed that young children could safely undergo peanut oral immunotherapy in real-world environments. The target maintenance dose of 300 milligrams of peanut protein is small, but it would ease anxiety among peanut allergy sufferers and their parents about cross- contamination or accidental exposure.

Soller, L., et al. First real-world safety analysis of preschool peanut oral immunotherapy. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2019.04.010 (April 16)

Super-Black Peacock Spiders

The secret to peacock spiders’ brilliant colors lies in their super-black patches. Male peacock spiders have brightly colored abdomens that they wave in courtship displays. A team of biologists used electron microscopy and hyperspectral imaging to examine the deep black areas that abut colors. They found that tiny bumps act as microlenses that decrease reflections, resulting in super-black regions that reflect less than 0.5 percent of light. Vertebrates see reflections as white highlights, which they use as reference points to calibrate colors. Eliminating these highlights makes nearby colors appear brighter. Birds of paradise also have super-black feathers that seem to make their other colors glow. The convergent evolution of super black in both birds and spiders suggests that it may play a role in the sexual displays of ecologically similar species.

Jean Hort/Flickr/CC BY 2.0

McCoy, D. E., et al. Structurally assisted super black in colourful peacock spiders. Proceedings of the Royal Society B doi:10.1098/rspb.2019.0589 (May 15)

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.