This Article From Issue

July-August 2008

Volume 96, Number 4

Page 345

DOI: 10.1511/2008.73.345

American Chestnut: The Life, Death, and Rebirth of a Perfect Tree. Susan Freinkel. xii + 284 pp. University of California Press, 2007. $27.50.

I began reading Susan Freinkel's new book, American Chestnut, on my porch one cool evening as darkness set in. It seemed the perfect setting for a story sure to be gloomy: a tale of the functional extinction of what was once one of the most economically valuable and ecologically important trees in the eastern United States.

Chestnut blight was caused by a fungus eventually determined to be Cryphonectria parasitica. It was probably imported to the United States on the Chinese or Japanese species of the tree, which both show resistance to it. The blight destroyed billions of American chestnut trees in the first half of the 20th century. The loss of the chestnut, in terms of the sheer number of trees killed, the size of its range before the blight, and the variety of habitats affected by its demise, is unrivaled in the history of human-wrought ecological disasters, even though epidemics such as Dutch elm disease have received more attention.

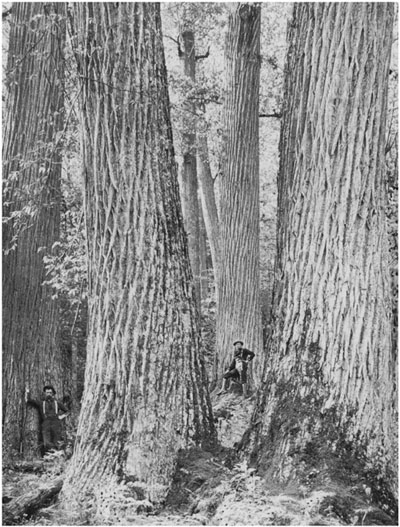

From American Chestnut.

Ecologists have long bemoaned the destruction of the American chestnut, but the general public has been far less aware of the magnitude of the blight's effects. As Freinkel appropriately points out, nearly everyone noticed the downfall of the American elm, because it was an urban shade tree, whereas the loss of the chestnut was most acutely felt by rural Americans whose histories were oral rather than written. The nuts were an important cash crop for them, and they found many uses for its timber and bark. The chestnut's former importance in the southern Appalachian Mountains, where it grew to its greatest size, lives on in place names such as Chestnut Ridge and Yellow Mountain (referring to the splash of color when the chestnuts were in bloom).

The chestnut can be considered an iconic American tree for many reasons, not the least of which is the reference to chestnuts roasting on an open fire in "The Christmas Song," by Mel Tormé and Bob Wells. Ironically, the song was written in 1944, just as the last wild American chestnuts were succumbing to the blight. By 1946, at the peak of the song's popularity, it would have been hard to find any American chestnuts to roast.

The American chestnut had valuable traits that made it superior in a number of ways both to the closely related Chinese chestnut species and to some Eastern forest species. For one thing, it was aggressive and could compete more effectively with other types of trees. Also, by most accounts American chestnuts were more flavorful than their Chinese cousins. And unlike many other large-seeded species—hickory and oak, for example—which have good production of mast (the nuts that accumulate on the forest floor) one year and poor production the next, the American chestnut produced a great deal of mast fairly consistently, making it a reliable source of food for wildlife.

In addition, wood from the tree was easy to work and resistant to rot—in the southern Appalachians it is still possible to find cabins and barns made of chestnut wood. The American chestnut could also regenerate rapidly from cut stumps and grow high-quality wood in the process. At one point the trees provided about two thirds of the tannic acid (used in the leather-tanning industry) produced in the United States.

Ecologists recognize that if you leave a place and travel through space or time, you will encounter ecological communities that are increasingly differentiated from the one that served as your starting point. This concept is called "the distance decay of similarity," and it echoes throughout Freinkel's book—first in the recognition that human-introduced diseases can hasten distance decay, and second, in the ongoing attempts to slow that process by restoring the species to its original condition. This theme is enriched by Freinkel's masterful interweaving of the cultural and biological history of the American chestnut tree with an account of the science of its restoration.

One approach to restoration has been to introduce genes for resistance to the fungus by crossbreeding American chestnuts with the resistant Chinese species. The first step is to backcross resistant hybrids and genetically pure American chestnuts for three generations (a process that takes decades), producing a tree that is fifteen-sixteenths American. Ideally, that tree will have the rapid growth in height and straight trunk of the American chestnut and will take from the Chinese species only the two or three genes known to confer resistance. However, meiotic recombinations make targeting specific genes an arduous business. Chestnuts have thousands of genes, and even the one-sixteenth of these that would have come from the Chinese species could confer numerous undesirable traits. The likely result will be the creation of trees that are lacking some of the genes required to restore the American chestnut to its former sylvan dominance.

Another restoration strategy involves inoculating trees with a weakened form of the blighting fungus. This idea arose after chestnut populations in several places were discovered to be recovering from blight; investigation revealed that the fungus on those trees had been infected with a hypovirus. The idea of using the hypovirulent fungus to inoculate trees seemed promising, but it hasn't worked very well in practice. Complicating matters are the genetic differences between individual trees and the fact that there are hundreds of strains of the blight fungus and four variants of the hypovirus.

Yet another approach, one that has encountered opposition, has been to use transgene technology to place genes from plants such as wheat into American chestnuts to enhance resistance to the fungus. Blight-resistant transgenic chestnut trees may someday shade our descendants, but at this point only a few transgenic chestnut treelets exist, and no one knows yet whether their ability to resist blight will be adequate.

Finally, there is always the possibility that somewhere in the American chestnut tree's native range, there are trees capable of resisting the blight just long enough to reproduce; I have twice seen in the wild American chestnuts with burs containing seeds, indicating that reproduction had occurred. Perhaps mutation and natural selection can yet produce a truly blight-resistant American chestnut.

On warm days, I like to take the students in my biology classes on walks to examine plant diversity, and I always include a stop at a Dunstan chestnut (a Chinese-American hybrid) to tell them about the demise of the American chestnut. Although I have long known the history and have kept up with the recovery efforts, now, drawing on Freinkel's book, I can add some texture to that story by telling them about key people, personalities and places. I can also end my account, as Freinkel does, with the hope that further research on hypovirulence and ongoing hybridization efforts will restore the chestnut to some small fraction of its former glory.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.