Bicycle: The History, Life at the Zoo and All in My Head

By David Schoonmaker, Christopher Brodie, Amos Esty

Short takes on three books

Short takes on three books

DOI: 10.1511/2005.53.0

Before reading David V. Herlihy's Bicycle: The History (Yale University Press, $35), it hadn't even occurred to me to wonder what led Wilbur and Orville Wright to drift from building bicycles to inventing aircraft. Now I think I know. Among the many things I learned from this lovingly written and beautifully illustrated volume was that the late 1890s marked the end of the cycling boom brought on by the arrival of the safety bicycle in the United States. Between 1896 and 1902, U.S. production fell from "1.2 million bicycles a year to about a quarter of that figure." The Wrights, I surmise, were in need of a new line of work.

From Bicyle: The History.

The crash that launched flight was just one of many boom-bust cycles that seem to have characterized bicycle popularity for most of two centuries. Herlihy carefully plots the course of these ups and downs and fits the technology that drove the roller coaster deftly into its cultural context. There's no need to be a cyclist to enjoy this ride.—D.R.S.

Maybe it's our latent totemism that makes seeing large animals like apes and tigers in the flesh such a profound experience. We admire the powerful efficiency of their movements, and they remind us of our own animal nature. These feelings seem to stir particularly in kids, whose growing interest in the natural world often crystallizes around macrofauna. Thus many readers will open Life at the Zoo (Columbia University Press, $27.95) with youthful delight. Author Phillip T. Robinson can describe with authority the inner workings of a modern zoological park—he is the long-time veterinarian of the San Diego Zoo. He traces the evolution of wild-animal collections from cruel menageries to sophisticated vehicles for education and conservation—changes that are remarkably recent and, unfortunately, not yet universal.

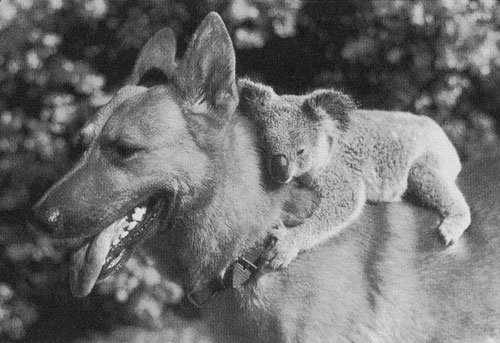

From Life at the Zoo.

Robinson peppers the text with charming anecdotes from his decades of experience. In one of these engrossing asides, after noting that semidomestication is the key to making captivity tolerable for a koala, he describes conditioning one to the point of tolerating canine transport (see above right). Unfortunately, his writing alternately lumbers and caroms, and it is likely to remind the reader by turns of the anesthetized elephant and the hyperactive antelope described in the text. Despite its rough stylistic edges, the book is compelling and ought to appeal to zoo lovers of all stripes.—C.B.

Paula Kamen has had a headache for nearly 15 years. Her search for relief has led her to try (among other things) acupuncture, massage, yoga, Xanax, Botox, vibrating hats, magnets, surgery, Prozac and giving up coffee. She recounts the frustrating shortcomings of these treatments in All in My Head: An Epic Quest to Cure an Unrelenting, Totally Unreasonable, and Only Slightly Enlightening Headache (Da Capo, $24.95).

Kamen's plight is far from unique. Millions of Americans suffer from chronic daily headache. Yet little is known about its causes, and treatment is often inadequate. One problem, Kamen says, is that many doctors continue to believe (against growing neurological evidence) that daily headache is a mental rather than physical condition. She points out that most sufferers are women and details the long tradition in medicine of questioning female patients' motivations when they complain of symptoms that are difficult to treat. If doctors would admit how little they know about chronic pain, she suggests, perhaps they would be less likely to blame their patients.

Kamen's quest is not over—she continues to experience the headaches—but she has reached greater acceptance. Through a combination of prescription drugs and alternative medicine she has learned to cope with the constant pain. Her wry outlook prevents the book from lapsing into self-pity. Extensively researched, it is a useful source of information about the history of the condition and current treatments. Kamen spent much of the first few years of her illness being told that she was the cause of the problem. Her saga, she hopes, will help convince others that chronic headaches are not simply "all in your head."—A.E.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.