Automation on the Job

By Brian Hayes

Computers were supposed to be labor-saving devices. How come we're still working so hard?

Computers were supposed to be labor-saving devices. How come we're still working so hard?

DOI: 10.1511/2009.76.10

Automation was a hot topic in the 1950s and ’60s—a subject for congressional hearings, blue-ribbon panels, newspaper editorials, think-tank studies, scholarly symposia, documentary films, World’s Fair exhibits, even comic strips and protest songs. There was interest in the technology itself—everybody wanted to know about “the factory of the future”—but the editorials and white papers focused mainly on the social and economic consequences of automation. Nearly everyone agreed that people would be working less once computers and other kinds of automatic machinery became widespread. For optimists, this was a promise of liberation: At last humanity would be freed from constant toil, and we could all devote our days to more refined pursuits. But others saw a threat: Millions of people would be thrown out of work, and desperate masses would roam the streets.

Photographs by Brian Hayes.

Looking back from 50 years hence, the controversy over automation seems a quaint and curious episode. The dispute was never resolved; it just faded away. The factory of the future did indeed evolve; but at the same time the future evolved away from the factory, which is no longer such a central institution in the economic scheme of things, at least in the United States. As predicted, computers guide machine tools and run assembly lines, but that’s a minor part of their role in society. The computer is far more pervasive in everyday life than even the boldest technophiles dared to dream back in the days of punch cards and mainframes.

As for economic consequences, worries about unemployment have certainly not gone away—not with job losses in the current recession approaching 2 million workers in the U.S. alone. But recent job losses are commonly attributed to causes other than automation, such as competition from overseas or a roller-coaster financial system. In any case, the vision of a world where machines do all the work and people stand idly by has simply not come to pass.

In 1930 the British economist John Maynard Keynes published a short essay titled “Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren.” At the time, the economic possibilities looked pretty grim, but Keynes was implacably cheerful. By 2030, he predicted, average income would increase by a factor of between four and eight. This prosperity would be brought about by gains in productivity: Aided by new technology, workers would produce more with less effort.

Keynes did not mention automation—the word would not be introduced until some years later—but he did refer to technological unemployment, a term that goes back to Karl Marx. For Keynes, a drop in the demand for labor was a problem with an easy solution: Just work less. A 3-hour shift and a 15-hour workweek would become the norm for the grandchildren of the children of 1930, he said. This would be a momentous development in human history. After millennia of struggle, we would have finally solved “the economic problem”: How to get enough to eat. The new challenge would be the problem of leisure: How to fill the idle hours.

Decades later, when automation became a contentious issue, there were other optimists. The conservative economist Yale Brozen wrote in 1963:

Perhaps the gains of the automation revolution will carry us on from a mass democracy to a mass aristocracy.... The common man will become a university-educated world traveler with a summer place in the country, enjoying such leisure-time activities as sailing and concert going.

But others looked at the same prospect and saw a darker picture. Norbert Wiener had made important contributions to the theory of automatic control, but he was wary of its social implications. In The Human Use of Human Beings (1950) he wrote:

Let us remember that the automatic machine... is the precise economic equivalent of slave labor. Any labor which competes with slave labor must accept the economic conditions of slave labor. It is perfectly clear that this will produce an unemployment situation, in comparison with which the present recession and even the depression of the thirties will seem a pleasant joke.

A. J. Hayes, a labor leader (and no relation to me), wrote in 1964:

Automation is not just a new kind of mechanization but a revolutionary force capable of overturning our social order. Whereas mechanization made workers more efficient—and thus more valuable—automation threatens to make them superfluous—and thus without value.

Keynes’s “problem of leisure” is also mentioned with much anxiety throughout the literature of the automation era. In a 1962 pamphlet Donald N. Michael wrote:

These people will work short hours, with much time for the pursuit of leisure activities.... Even with a college education, what will they do all their long lives, day after day, four-day weekend after weekend, vacation after vacation...?

The opinions I have cited here represent extreme positions, and there were also many milder views. But I think it’s fair to say that most early students of automation, including both critics and enthusiasts, believed the new technology would lead us into a world where people worked much less.

Keynes’s forecast of growth in productivity and personal income seemed wildly optimistic in 1930, but in fact he underestimated. The upper bound of his prediction—an eightfold increase over 100 years—works out to an annual growth rate of 2.1 percent. So far, the observed average rate comes to 2.9 percent per year. If that rate is extrapolated to 2030, worldwide income will have increased by a factor of 17 in a century. (These calculations are reported by Fabrizio Zilibotti of the University of Zurich in a recent book reassessing Keynes’s 1930 essay.)

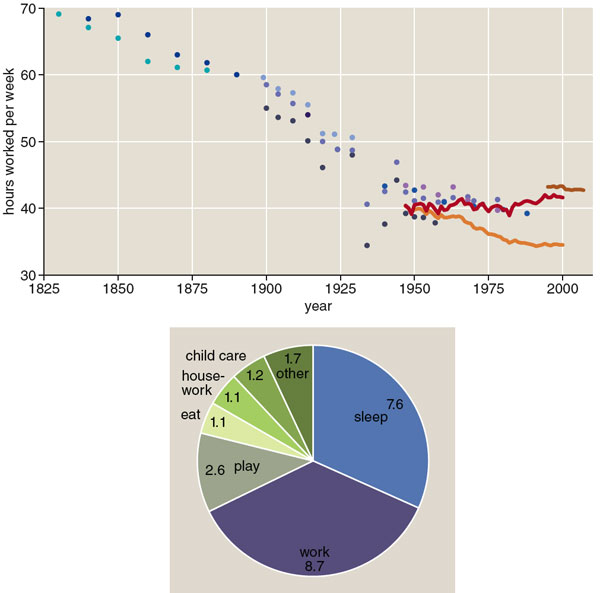

Keynes’s promise of affluence has already been more than fulfilled—at least for citizens of wealthier nations. It’s a remarkable achievement, even if we have not yet truly and permanently “solved the economic problem.” If Keynes was right about the accumulation of wealth, however, he missed the mark in predicting time spent on the job. By most estimates, the average workweek was about 60 hours in 1900, and it had fallen to about 50 hours when Keynes wrote in 1930. There was a further decline to roughly 40 hours per week in the 1950s and ’60s, but since then the workweek has changed little, at least in the U.S. Western Europeans work fewer hours, but even there the trend doesn’t look like we’re headed for a 15-hour week anytime soon.

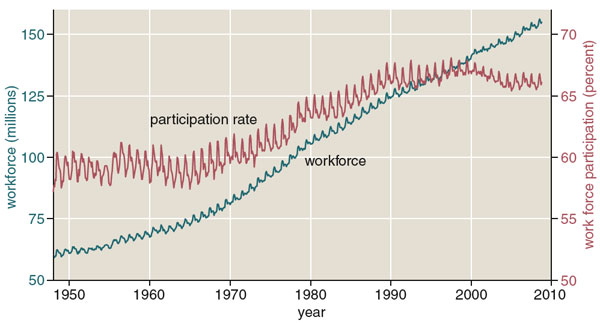

Other measures of how hard people are working tell a similar story. The total labor force in the U.S. has increased by a factor of 2.5 since 1950, growing substantially faster than the working-age population. Thus labor-force participation (the percentage of people who hold jobs, among all those who could in principle be working) has risen from 59 percent to 66 percent.

These trends contradict almost all the expectations of early writers on automation, both optimists and pessimists. So far, automation has neither liberated us from the need to work nor deprived us of the opportunity to work. Instead, we’re working more than ever.

Economists reflecting on Keynes’s essay suggest he erred in supposing that people would willingly trade income for leisure. Instead, the commentators say, people work overtime to buy the new wide-screen TV even if they then have no time to enjoy it. Perhaps so. I would merely add that many who are working long hours (postdocs, say, or parents of young children) do not see their behavior as a product of conscious choice. And they do not think society has “solved the economic problem.”

Perhaps the most thoughtful and knowledgeable of the early writers on automation was John Diebold, a consultant and author. It was Diebold who introduced the word automation in its broad, modern sense. He clearly understood that there was more to it than reducing labor costs in factories. He foresaw applications to many other kinds of work, including clerical tasks, warehousing and even retailing. Nevertheless, when he chose examples for detailed description, they almost always came from manufacturing.

Automatic control first took hold in continuous-process industries such as oil refining. A closed-loop control mechanism could regulate the temperature of a distilling tower, eliminating the need for a worker to monitor a gauge and adjust valve settings. As such instruments proliferated, a refinery became a depopulated industrial landscape. An entire plant could be run by a few technicians, huddled together in a glass-walled control room. This hands-off mode of operation became the model that other industries strove to emulate.

In the automation literature of the 1950s and ’60s, attention focuses mainly on manufacturing, and especially on the machining of metal. A celebrated example was the Ford Motor Company’s Cleveland Engine Plant No. 1, built in 1951, where a series of interconnected machines took in raw castings at one end and disgorged finished engine blocks at the other. The various tools within this complex performed several hundred boring and milling operations on each engine, with little manual intervention.

A drawback of the Ford approach to automation was inflexibility. Any change to the product would require an extensive overhaul of the machinery. But this problem was overcome with the introduction of programmable metalworking tools, which eventually became computer-controlled devices.

Other kinds of manufacturing also shifted to automated methods, although the result was not always exactly what had been expected. In the early years, it was easy to imagine a straightforward substitution of machines for labor: Shove aside a worker and install a machine in his or her place. The task to be performed would not change, only the agent performing it. The ultimate expression of this idea was the robot—a one-for-one replacement for the factory worker. But automation has seldom gone this way.

Consider the manufacture of electronic devices. At the outset, this was a labor-intensive process of placing components on a chassis, stringing wires between them and soldering the connections one by one. Attempts to build automatic equipment to perform the same operations proved impractical. Instead, the underlying technology was changed by introducing printed circuit boards, with all the connections laid out in advance. Eventually, machines were developed for automatically placing the parts on the boards and for soldering the connections all at once.

The further evolution of this process takes us to the integrated circuit, a technology that was automated from birth. The manufacture of microprocessor chips could not possibly be carried out as a handicraft business; no sharp-eyed artisan could draw the minuscule circuit patterns on silicon wafers. For many other businesses as well, manual methods are simply unthinkable. Google could not operate by hiring thousands of clerks to read Web pages and type out the answers to queries.

The automation of factories has gone very much according to the script written by Diebold and other early advocates. Computer control is all but universal. Whole sections of automobile assembly plants are now walled off to exclude all workers. A computer screen and a keyboard are the main interface to most factory equipment.

Meanwhile, though, manufacturing as a whole has become a smaller part of the U.S. economy—12 percent of gross domestic product in 2005, down from more than double that in the 1950s. And because of the very success of industrial automation, employment on production lines has fallen even faster than the share of GDP. Thus, for most Americans, the factory automation that was so much the focus of early commentary is all but invisible. Few of us ever get a chance to see it at work.

But automation and computer technology have infiltrated other areas of the economy and daily life—office work, logistics, commerce, finance, household tasks. When you look for the impact of computers on society, barcodes are probably more important than machine tools.

In the 1950s, digital computers were exotic, expensive, unapproachable and mysterious. It was far easier to see such a machine becoming the nexus of control in a vast industrial enterprise than to imagine the computer transformed into a household object, comparable to a telephone or a typewriter—or even a toy for the children to play with. Donald Michael wrote:

Most of our citizens will be unable to understand the cybernated world in which they live.... There will be a small, almost separate, society of people in rapport with the advanced computers.... Those with the talent for the work probably will have to develop it from childhood and will be trained as intensively as the classical ballerina.

If this attitude of awestruck reverence had persisted, most of the computer’s productive potential would have been wasted. Computers became powerful when they became ubiquitous—not inscrutable oracles guarded by a priestly elite but familiar appliances found on every desk. These days, we are all expected to have rapport with computers.

The spread of automation outside of the factory has altered its social and economic impact in some curious ways. In many cases, the net effect of automation is not that machines are doing work that people used to do. Instead we’ve dispensed with the people who used to be paid to run the machines, and we’ve learned to run them ourselves. When you withdraw money from the bank via an ATM, buy an airline ticket online, ride an elevator or fill up the gas tank at a self-service pump, you are interacting directly with a machine to carry out a task that once required the intercession of an employee.

The dial telephone is the archetypal example. My grandmother’s telephone had no dial; she placed calls by asking a switchboard operator to make the connection. The dial (and the various other mechanisms that have since replaced it) empowers you to set up the communications channel without human assistance. Thus it’s not quite accurate to say that the operator has been replaced by a machine. A version of the circuit-switching machine was there all along; the dial merely provided a convenient interface to it.

The process of making travel arrangements has been transformed in a similar way. It was once the custom to telephone a travel agent, who would search an airline database for a suitable flight with seats available. Through the Web, most of us now access that database directly; we even print our own boarding passes. Again, what has happened here is not exactly the substitution of machines for people; it is a matter of putting the customer in control of the machines.

Other Internet technologies are taking this process one more dizzy step forward. Because many Web sites have published interface specifications, I now have the option of writing a program to access them. Having already removed the travel agent, I can now automate myself out of the loop as well.

Enabling people to place their own phone calls and make their own travel reservations has put whole categories of jobs on the brink of extinction. U.S. telephone companies once employed more than 250,000 telephone operators; the number remaining is a tenth of that, and falling fast. It’s the same story for gas-station attendants, elevator operators and dozens of other occupations. And yet we have not seen the great contraction of the workforce that seemed inevitable 50 years ago.

Brian Hayes

One oft-heard explanation holds that automation brings a net increase in employment by creating jobs for people who design, build and maintain machines. A strong version of this thesis is scarcely plausible. It implies that the total labor requirement per unit of output is higher in the automated process than in the manual one; if that were the case, it would be hard to see the economic incentive for adopting automation. A weaker but likelier version concedes that labor per unit of output declines under automation, but total output increases enough to compensate. Even for this weaker prediction, however, there is no guarantee of such a rosy outcome. The relation may well be supported by historical evidence, but it has no theoretical underpinning in economic principles.

For a theoretical analysis we can turn to Herbert A. Simon, who was both an economist and a computer scientist and would thus seem to be the ideal analyst. In a 1965 essay, Simon noted that economies seek equilibrium, and so “both men and machines can be fully employed regardless of their relative productivity.” It’s just a matter of adjusting the worker’s wage until it balances the cost of machinery. Of course there’s no guarantee that the equilibrium wage will be above the subsistence level. But Simon then offered a more complex argument showing that any increase in productivity, whatever the underlying cause, should increase wages as well as the return on capital investment. Do these two results add up to perpetual full employment at a living wage in an automated world? I don’t believe they offer any such guarantee, but perhaps the calculations are reassuring nonetheless.

Another kind of economic equilibrium also offers a measure of cheer. The premise is that whatever you earn, you eventually spend. (Or else your heirs spend it for you.) If technological progress makes some commodity cheaper, then the money that used to go that product will have to be spent on something else. The flow of funds toward the alternative sectors will drive up prices there and create new economic opportunities. This mode of reasoning offers an answer to questions such as, “Why has health care become so expensive in recent years?” The answer is: Because everything else has gotten so cheap.

I can’t say that any of these formulations puts my mind at ease. On the other hand, I do have faith in the resilience of people and societies. The demographic history of agriculture offers a precedent that is both sobering and reassuring. It’s not too much of an exaggeration to say that before 1800 everyone in North America was a farmer, and now no one is. In other words, productivity gains in agriculture put an entire population out of work. This was a wrenching experience for those forced to leave the farm, but the fact remains that they survived and found other ways of life. The occupational shifts caused by computers and automation cannot possibly match the magnitude of that great upheaval.

What comes next in the march of progress? Have we reached the end point in the evolution of computerized society?

Since I have poked fun at the predictions of an earlier generation, it’s only fair that I put some of my own silly notions on the record, giving some future pundit a chance to mock me in turn. I think the main folly of my predecessors was not being reckless enough. I’ll probably make the same mistake myself. So here are three insufficiently outrageous predictions.

1. We’ll automate medicine. I don’t mean robot surgeons, although they’re in the works too. What I have in mind is Internet-enabled, do-it-yourself diagnostics. Google is already the primary-care physician for many of us; that role can be expanded in various directions. Furthermore, as mentioned above, medical care is where the money is going, and so that’s where investment in cost-saving technologies has the most leverage.

2. We’ll automate driving. The car that drives itself is a perennial on lists of future marvels, mentioned by a number of the automation prophets of the 50s and 60s. A fully autonomous vehicle, able to navigate ordinary streets and roads, is not much closer now than it was then, but a combination of smarter cars and smarter roads could be made to work. Building those roads would require a major infrastructure project, which might help make up for all the disemployed truckers and taxi drivers. I admit to a certain boyish fascination with the idea of a car that drops me at the office and then goes to fetch the dry cleaning and fill up its own gas tank.

3. We’ll automate warfare. I take no pleasure in this one, but I see no escaping it either. The most horrific weapons of the 20th century had the redeeming quality that they are difficult and expensive to build, and this has limited their proliferation. When it comes to the most fashionable weapons of the present day—pilotless aircraft, cruise missiles, precision-guided munitions—the key technology is available on the shelf at Radio Shack.

What about trades closer to my own vital interests? Will science be automated? Technology already has a central role in many areas of research; for example, genome sequences could not be read by traditional lab-bench methods. Replacing the scientist will presumably be a little harder that replacing the lab technician, but when a machine exhibits enough curiosity and tenacity, I think we’ll just have to welcome it as a companion in zealous research.

And if the scientist is elbowed aside by an automaton, then surely the science writer can’t hold out either. I’m ready for my 15-hour workweek.

©Brian Hayes

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.