Flash Upon a Neutron Star

By Michael Szpir

Innovative movies make an x-ray burst visible

Innovative movies make an x-ray burst visible

DOI: 10.1511/2000.35.0

The universe is chock-full of exotic things that, for various reasons, most human eyes will never see: A summer's day on a planet in another galaxy, the extruded internal organs of a frightened sea cucumber, and true romantic love—to name just a few. In a wistful mood one might add to the list a bird's-eye view of a neutron star during an x-ray burst. Such a sight is a near impossibility—with its crushing gravity and searing radiation, a neutron star would extinguish a would-be visitor before he got close enough to have a look. But those who pine for such things can now rest a little easier: In our age of parallel supercomputers, scientists can now bring a darned good simulation of the real thing onto your desktop. Why risk being assimilated into a pile of neutrons when you can see the sights from the comfort of your easy chair?

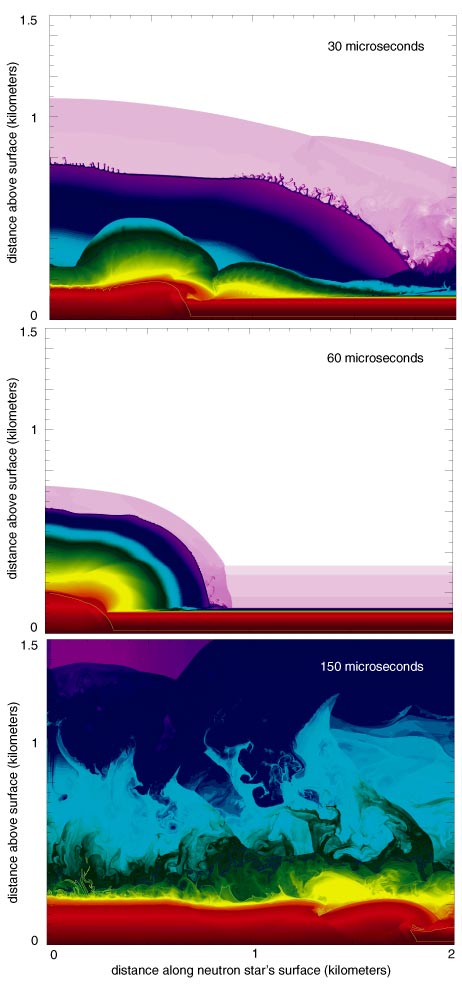

Michael Zingale, along with Frank Timmes, Bruce Fryxell, Don Lamb and colleagues at the University of Chicago, have created a couple of movies that offer a glimpse of a neutron star's surface as it might appear during the detonation of some wayward matter that got too close to the star. Each movie—one shows temperature changes, the other density changes—is about 45 seconds long and presents the first 150 microseconds of a thermonuclear flash exploding into the star's atmosphere (see captured frames, right).

Such thermonuclear flashes are thought to be a source of the sudden bursts of x rays that astronomers have been detecting with orbiting telescopes since the 1970s. Theory holds that x-ray bursts occur in binary-star systems involving a neutron star and a nearby stellar companion as matter is pulled from the companion onto the compact star. When the accreting matter (helium) reaches a sultry 250 million degrees it detonates, and all hell breaks loose. High-energy photons (x rays) are sent hurtling into space in the process.

Simulating the surface events of an x-ray burst is no small accomplishment. It involves modeling a broad range of physical phenomena—including convection and turbulence at large Reynolds and Rayleigh numbers, equations of state for high-density matter and nuclear processing (among other processes)—that are a computational nightmare. The problems are similar to the computational challenges faced by the nuclear weapons program in stockpile stewardship, and this may explain why the Department of Energy is providing financial support for the research.

Readers should note that the captured stills from the movie don't do it justice. So heat up some popcorn, invite your significant other over this evening, and download the movie from the Internet at http://flash.uchicago.edu/~zingale/xray_gallery/xray_gallery.html. It may not be better than true love, but it's more interesting than the sea cucumber act.—Michael Szpir

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.