This Article From Issue

May-June 2005

Volume 93, Number 3

DOI: 10.1511/2005.53.0

The Newtonian Moment: Isaac Newton and the Making of Modern Culture. Mordechai Feingold. xv + 218 pp. New York Public Library and Oxford University Press, 2004. $22.50.

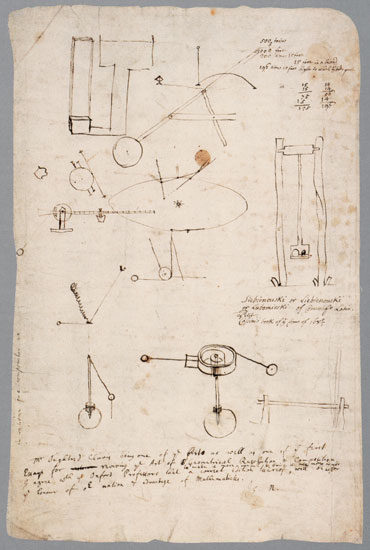

The exhibits of Newton's works at Cambridge University Library in 2001 and at the New York Public Library from October 8, 2004, to February 5, 2005, were of note, among other reasons, for the attention they drew to a December 2004 auction of rare Newton manuscripts. Mordechai Feingold has, meanwhile, created a lavishly illustrated and immensely entertaining companion volume to the New York display of Newton's great achievement. The book serves to demonstrate that the rationalism of the European Enlightenment, which was marked by upheaval in America and in France, was defined in such large measure by the conception and diffusion of Newton's great works in mathematics and physics that the epoch could be viewed as the Newtonian Moment.

From The Newtonian Moment

Here is a Newton deified, not only in a state funeral at Westminster Abbey (rare for a philosopher) but also by endless numbers of paintings and engravings of the great man—some of which Newton himself distributed. Gentlemanly experimental philosophers, even amateur ones, later took pains when having their own portraits painted to have apparatus and portraits of Newton and Bacon in the background. Thomas Jefferson was so smitten that he obtained one of the few copies of Newton's death mask made in 1727. The colossus of Newton strode across the 18th century, subduing nature, even as Alexander Pope eulogized him with this couplet: "Nature, and Nature's Laws lay hid in Night. / God said, 'Let Newton be!' and all was Light."

From the moment of Newton's death, even amid the controversies that surrounded his greatest accomplishments in mathematics, physics and chemistry, the philosopher was to be emulated. By mid-century, Newton was the highest embodiment of reason, even for French philosophes. For Denis Diderot and for Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Newton represented the ultimate fulfillment of the Baconian program of experiment. But for Rousseau, even moral philosophy could be expanded by the Newtonian method—as Newton himself had proclaimed in his Opticks, a work that his executor John Conduitt believed "joined Morality to Philosophy." Thus the grand image of Newton was manufactured.

Feingold engages in his own revision of Newton's autocratic image. He reveals a Newton surrounded by conflict, battling Robert Hooke, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz and innumerable others over optics in particular, and contending with some who were highly suspicious of his theological sentiments. Feingold advances the debate among scholars over Newton's sporadic withdrawal from philosophic dispute, suggesting particularly that Hooke's real animosity was not quite so personal as it has been portrayed. The actual issues, Feingold maintains, had to do at least in part with the failure of Newton to provide a physical explanation for his prismatic experiments. Likewise, Newton's differences with Leibniz were not entirely about the invention of the calculus, although this later became a cause célèbre as Newton used his presidency of the Royal Society to advance his claims. Rather, the conflict followed upon the antagonism toward Leibniz of Newton's disciples John Keill and Nicolas Fatio de Duillier, a Swiss mathematician who was supposedly "mentally unstable." But this assertion is as speculative, it seems to me, as the previously proposed theory that there was a deeply intense relationship between Fatio and Newton, the collapse of which contributed to Newton's own mental breakdown in the 1690s.

Amid the controversies swirling around Newton's achievements, the "near-total incomprehension" of those who read the Principia was a major hurdle overcome only by the increasing efforts of scientific amateurs. Feingold demonstrates that Newton's reputation owed much to those who could barely understand his great mathematical achievements. Indeed, even those versed in mathematics sought out assistance from the few individuals who had been initiated into the calculus of motions. The dissemination of Newton's experimental science, which enhanced the importance of instruments in natural philosophy, is suggested to have originated in the lectures of John Keill at Oxford. Although a more convincing claim for influence might well be made for the lecturer John Harris or even James Hodgson, a teacher of mathematics who made experimental apparatus essential, these are mere quibbles. Those who were enamored of experiments—for example, Willem Jacob 's Gravesande and Hermann Boerhaave in Holland, and Voltaire in France—were fundamental to the spread of Newton's method, as were those who declared that they found much to admire in the English world of religious pluralism and experimental philosophy. Even the ultimate rescue of the reputation of French science at the end of the century, by the innovative chemistry of Lavoisier, owed much to the development of the experimental world by Newton's disciples.

Feingold's work is full of insight into how Newton made the Enlightenment and what use the Enlightenment made of him. Two reproductions of the broadsheets of Newton's disciple William Whiston are hopelessly small, but apart from that, this work is brilliantly illustrated. Indeed, illustration was at the very center of Newton's reputation. An engraving made by Bernard Picart in 1707, which showed Descartes (followed by Aristotle, Plato, Socrates and Zeno) being led by Lady Philosophy toward Truth, was appropriated by the English, who replaced the image of Descartes with that of Newton and altered the accompanying text to indicate that Newton's explanation of gravity had shattered Cartesian vortices. Gravity, it seems, put Newton at the center of the European achievement that so impressed Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson as they manufactured their own revolution.—Larry Stewart, History, University of Saskatchewan

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.