An Updated Prehistory of the Human Pelvis

By Caroline M VanSickle

Recent fossil discoveries are raising new questions about how the modern human pelvis developed its unique shape.

Recent fossil discoveries are raising new questions about how the modern human pelvis developed its unique shape.

DOI: 10.1511/2016.123.354

As a paleoanthropologist—a scientist who studies how humans evolved—I spend a lot of time looking at tiny fragments of bone. I ponder questions such as, How did Neanderthals give birth? When did our ancestors develop hips that distinguished the sexes? And, is this flat piece of bone a part of the shoulder blade or the hip?

Photograph courtesy of John Hawks/University of Wisconsin–Madison

My job involves identifying bone fragments, figuring out how they fit together into a skeleton, determining the species of that skeleton, and fitting that species into our lineage. It is a lot like working on a never-ending jigsaw puzzle without a box lid for guidance and with most of the puzzle pieces missing. I’ve been asked why anyone would pursue such a frustrating career, and at times that feels like a very good question. But curiosity wins out: The mystery of how humans came to be the only species of their kind on the planet is too tempting to ignore.

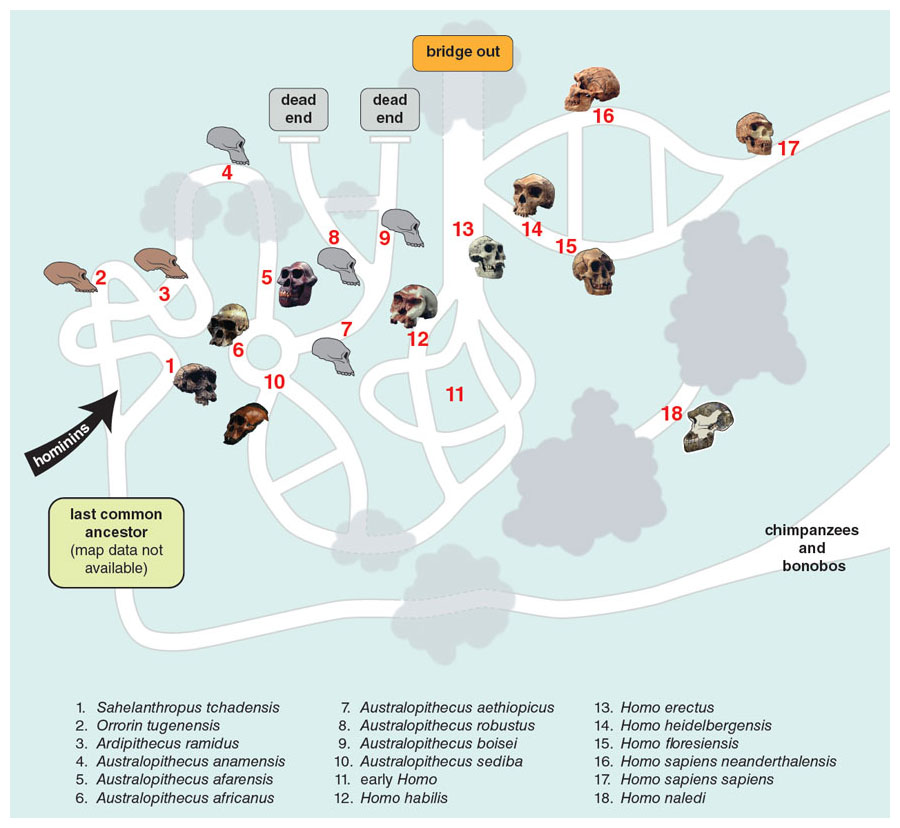

Sometime between 7 million and 13 million years ago, our lineage diverged from that of Pan troglodytes, the chimpanzee. Our last common ancestor with chimpanzees likely lived in an area with a lot of trees; scientists hypothesize that it would have had skeletal adaptations for moving around in trees and thus would have looked more similar in form to modern chimpanzees than to modern humans. After the split from this common ancestor, the path leading toward humans is populated with many different species, all called hominins (previously known as hominids, but renamed once we realized how closely humans and great apes are related). Some of these hominin species are our direct ancestors, whereas others are more like evolutionary cousins, descended from the ancestor we share with chimpanzees but not on the lineage that led to humans. Often it’s difficult to sort out which species are ancestors and which are cousins, especially because we have so few informative fossils to work with.

At the end of the 19th century, when Charles Darwin was writing about human evolution, many scholars thought the evolutionary path to humans was a straight line. This conception seemed reasonable at a time when we hadn’t yet found many types of hominin fossils: It was easy to imagine older-looking species coming first, followed by less old-looking species, and culminating in Homo sapiens sapiens.

Today, however, we have a lot more fossils to fit into the hominin lineage, and what we’ve found is that evolution rarely proceeds in a straight line. As with other animal species, our evolutionary history is complex, with certain traits evolving multiple times, more species diversity than was initially imagined, and few indicators of which path led to humans. This situation means that whenever fossil evidence of a new species is discovered, it has the potential tochange the entire “map” of human evolution. Lately the map has begun to look less like a direct route than the roadways of a complex city, complete with dead ends, detours, roundabouts, and side roads representing both the fossils we know and the hominin species we haven’t discovered yet.

My research focuses on the evolution of the pelvis, an important part of our evolutionary story because the pelvis of hominins differs dramatically from that of the chimpanzee—and possibly, therefore, from that of our last common ancestor. Paleoanthropologists generally agree that when hominins began walking on two legs, something we’ve been doing for more than three million years, the shape of the pelvis changed to accommodate our bipedal gait. The pelvis of a chimpanzee extends across the lower back to support the lower body when the animal is swinging through the trees; for a chimpanzee to walk on two legs, however, requires a lot of effort and energy. By contrast, in hominins the pelvis forms a squat, sturdy base that supports and balances the weight of the upper body when walking or standing on two legs without requiring much effort. Some version of this squatness is seen in every hominin pelvic fossil, although no two are identical. The exact shape differs subtly from one fossil species to another.

Illustration by Barbara Aulicino

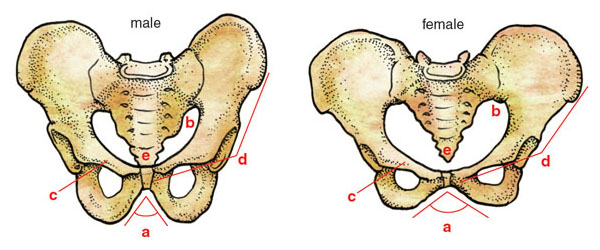

The pelvis itself is a complicated structure formed by two hipbones and a triangular bone called a sacrum. The sacrum sits at the base of the spine and the back of the pelvis. Together with the two hipbones, the resulting pelvis can be imagined as a sturdy ring of bone with two wings coming off the top on either side. You can feel the outer edges of the two wings by putting your hands on your hips. The ring protects the lower intestines and supports the weight of the upper body; additionally, in women the ring serves as the birth canal. Each hipbone includes an ilium (the wings and the top side part of the ring), an ischium (the bottom part of the ring), and a pubis (the front top part of the ring).

The ilium and ischium have undergone a lot of modification since the hominin line branched off from that of chimpanzees, so these parts of the human pelvis today look very different from the ilium and ischium of our nearest living relatives. In humans the wings of the ilium extend from either side of the pelvis; in contrast, the chimpanzee’s tall, narrow wings of the ilium extend from the back of the pelvic ring. Similarly, although humans have a short ischium on each side of the body to sit on, chimpanzees have long ischia.

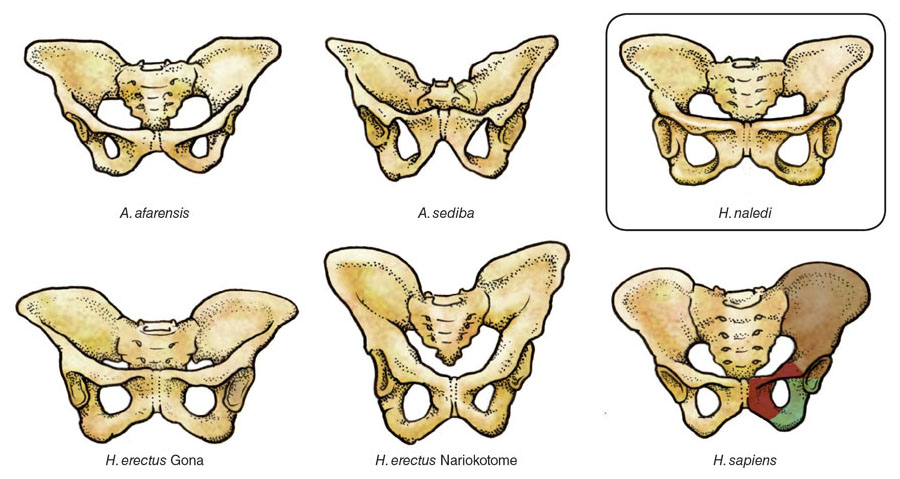

Among hominins, the iliac wings are located on the side, but the angle between the wings and the ring of bone varies from one species to another. In humans, the two wings approach being parallel, giving our hips an almost bowl-like shape when viewed from the front. At the other end of the hominin spectrum, Australopithecus afarensis (Lucy’s species) has ilia that angle out to the sides, giving the pelvis a flat, platelike shape when viewed from the front. In the pelvic fossils of other hominins, the ilia flare out to various degrees between Lucy’s extreme amount and humans’ near- absence of flare. The size of the ischium also differs among hominin species, ranging from remarkably long in Lucy to very short in humans.

Illustration by Emma Skurnick

For a long time, paleoanthropologists had thought that the differences among hominins could be explained by the space requirements of the birth canal. This explanation is now undergoing some change, however, as discussed in an American Scientist column by Pat Shipman (“Why Is Human Childbirth So Painful?,” November–December 2013). Chimpanzees, with their elongated pelvis (a product of the tall wings and long ischium), have a spacious birth canal that their small-brained infants fit through without difficulty. By comparison, the shorter ischium and reoriented ilium of the human pelvis produce a smaller birth canal, which—together with the development of larger-brained infants—can make childbirth both painful and problematic.

One generation's missing pieces of the puzzle can be the next generation's major new discoveries.

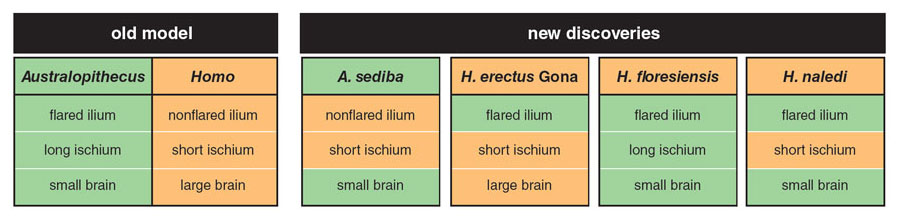

Paleoanthropologists have suggested that as birth became more complex, owing to an increase in brain size, the pelvis—especially the female pelvis—adapted to expand the birth canal. One apparent result of such adaptations is the set of skeletal features that distinguish female pelvises from male ones, irrespective of body size. Plausible as this model may be, however, it does not explain the pelvic evidence in the fossil record. Plenty of cranial fossils have been unearthed that show brain size started increasing around two million years ago, the time that our genus, Homo, emerged. Yet few pelvic fossils from that period have been uncovered. Up until about 15 years ago, the best-known pelvic remains of Australopithecus were two species with wide, platelike ilia and long ischia, and the only known pelvis from Homo erectus was one with narrow, bowl-shaped ilia and short ischia. This handful of somewhat-complete pelvic fossils in the hominin record seemed to support the concept of pelvic evolution as a process that moved in only one direction, with later hominins—including us—having a different pelvic shape (due to our increasing brain size) from the earlier, smaller-brained species.

Illustration by Emma Skurnick

It turns out, though, that some “missing pieces” of the never-ending puzzle play a key role here, because one generation’s missing pieces can be the next generation’s major new discoveries. In just the past 15 years, a terrific sequence of fossil finds has provided enough additional evidence to change the picture. It now appears that paleoanthropologists need to find a different explanation for hominin pelvis variation than birth adaptations, because the old model does not fit the new evidence.

In 2003, Peter Brown and Michael Morwood, both affiliated with the University of New England in Armidale, Australia, published a paper with their colleagues on a newly discovered human relative from Liang Bua Cave, on the island of Flores, Indonesia. They described Homo floresiensis, whom we now know lived around 100,000 years ago, as a small-bodied member of our genus; the media quickly dubbed them “hobbits.” Although the skeletal fossils generally appear similar to humans (thus classifying them in the genus Homo), the pelvis looks a lot like Lucy’s: The ilium sticks out at an angle, forming a plate instead of a bowl shape, and the ischium is extremely long. Pelvic anatomy of this kind had never before been seen in the genus Homo, and initially some argued that the surprising anatomy was the result of a pathology rather than indicating a new species. Today most paleoanthropologists accept that these fossils are not pathological humans but are indeed their own species; now the argument focuses on how closely they are related to other hominins and how they got to the island of Flores.

A very different example of our genus emerged in 2008, when Scott Simpson of Case Western Reserve University and his team published a paper on a complete female pelvis from Gona, Ethiopia. Unfortunately, this pelvis was found unassociated with any other fossils to help identify it; the layers of rock and sediment it was found between, however, dated it to between 900,000 and 1.4 million years ago. Only one species of human relative is known to have lived in East Africa at this time: Homo erectus, the first member of our genus to control fire and also to venture outside Africa.

Photograph courtesy of John Hawks/University of Wisconsin–Madison

Prior to this discovery, the fossil pelvis best known from H. erectus had been the 1.6-million-year-old specimen dubbed Nariokotome Boy, discovered near Lake Turkana in Kenya by Kamoya Kimeu of the National Museums of Kenya. When found, this male pelvis was crushed and incomplete, but by using the skeleton of a modern human boy for reference, paleoanthropologists Alan Walker of Pennsylvania State University and Christopher Ruff of Johns Hopkins School of Medicine made an initial reconstruction, which revealed a tall and narrow pelvis. In contrast, the Gona pelvis is short and wide, and also of a much smaller individual. The Gona pelvis has a shorter ischium than Lucy or the Liang Bua fossil, but it still has the wide, platelike ilium seen in earlier human ancestors. Some experts argue that its small size and Lucy-like ilia mean that it’s not H. erectus at all, but no clear consensus has been reached, owing to the lack of cranial evidence. If the Gona pelvis is ultimately classified as Homo erectus, the implication is that we have a fossil mystery on our hands: Now there are two species of Homo that have australopith-looking ilia. To deepen the mystery, this time it’s found in a species (H. erectus) known to have a larger brain than Lucy and her kin.

Not long after the discovery of late hominins with “primitive” pelvic structures came the discovery of a “modern” structure in an earlier species. In 2010, paleoanthropologist Lee Berger of the University of the Witwatersrand and his team announced a new species from South Africa. Named Australopithecus sediba, this species was represented by two partial skeletons, one from an adolescent male and the other from an elderly female. Both skeletons preserved pieces of the pelvis; thus, although neither pelvis was complete, each could be reconstructed using pieces from the other individual. The resulting pelvises are tall, with short ischia; in other words, they look like the pelvis of the Nariokotome H. erectus or of modern humans. The skull, teeth, arms, legs, and rib cage all resemble various species of Australopithecus, however, which is how this Homo-like pelvis ended up in a different genus. Yet A. sediba still presents a challenge: Without the need to adapt for the birth of large-brained babies, this species (which in most respects resembles Lucy) had no reason to evolve a pelvis like ours—at least, no reason that paleoanthropologists have yet been able to discern.

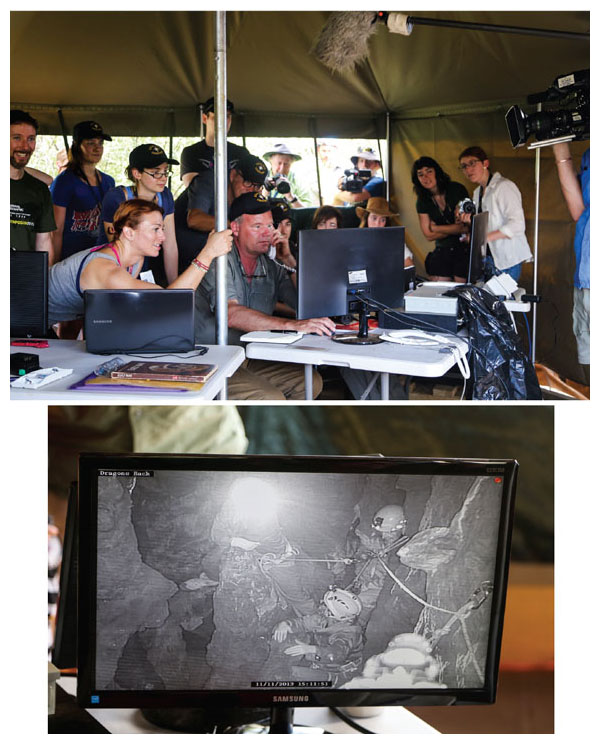

To cap off this sudden abundance of fossil evidence, 2015 saw the announcement of another new species, discovered in the most dramatic fashion yet. Outside of Johannesburg, South Africa, at the end of a narrow, twisted path deep in the Rising Star Cave, two cavers found a hidden chamber full of hominin bones—many more fossils than had ever been seen together at a single site in Africa. Berger, conveniently located nearby, rushed to assemble a team of excavators who met very specific criteria:These scientists had to be not only highly experienced at excavation, but also slight enough in stature to fit through passages less than 18 centimeters wide. The Rising Star team proceeded to excavate more than 1,500 fossils, truly a spectacular find.

Photograph courtesy of John Hawks/University of Wisconsin–Madison

Next, a large team of researchers from all over the world, most of them in the early stages of their career, analyzed the fossils and assigned them to a new hominin species, Homo naledi. (It was in the context of this research that I, as one of those early-career researchers, wondered whether some of the flat fragments were shoulder blade or hip bones). Most remarkable about this discovery was the sheer richness of the collection. Typically, paleoanthropologists will get excited about a single jawbone, because every missing puzzle piece is a cause for cheer. To find more than 1,500 fossils of the same species, representing nearly every part of the skeleton, including 41 pelvic fragments—often from multiple individuals of different ages—was like winning the paleoanthropological lottery.

Photographs (left) courtesy of John Hawks/University of Wisconsin–Madison. Image of reconstructed skull (right) by Brett Eloff Photography

But there was a catch: What these new fossils told us about hominin evolution was confusing. The discovery of H. naledi has definitely changed the map, and we’re still debating where the new roads should go. The fossils of H. naledi were the only fossils in the cave, so we can’t say which other species of animal lived alongside it. Unlike other cave sites, these bones were not encased in rock that would tell us when these individuals died; instead they were lying in sediment that cannot be easily dated. This all makes it especially difficult to determine when these creatures lived and died. Wherever H. naledi ends up in the timeline of hominin evolution, it will be unusual. Some of its features will look either too ancient or too modern for its date. The cranium resembles H. erectus; its torso appears similar to A. afarensis; and its legs and feet look like ours. (See also “The Latest on Homo naledi,” by John Hawks, Spotlight, July–August 2016.)

The pelvic remains, though fragmentary, clearly show that H. naledi had an ilium that, like Lucy’s, flared out at a wide angle. This configuration would have made the top part of the H. naledi pelvis more platelike than the bowl-shaped corresponding area in modern humans. The H. naledi ischium, however, is another story: It is short, unlike that of Lucy or the Liang Bua fossil, and closer in appearance to the ischium of the Gona and Nariokotome fossils and of humans today. Suddenly it appears that mixing primitive and modern pelvic traits was relatively common in the past, as we see from A. sediba, H. erectus, H. floresiensis, and H. naledi.

Barbara Aulicino

With these newer pieces of the puzzle in hand, paleoanthropologists are still trying to work out what the roadmap of evolution looked like. We now have three species of Homo with Australopithecus-like hips (or, at least, ilia) and one species of Australopithecus with humanlike hips. The conventional account—that pelvic shape evolved to adapt to increases in brain size—cannot explain these fossils, because one set of Australopithecus- lookinghips belongs to a larger-brained hominin, whereas a human-looking Australopithecus pelvis belongs to a small-brained hominin.

What’s more, we now have too much variation to continue thinking that pelvic evolution was a one-way street. As we redraw the map with each new discovery, we’re left with two big questions: Why did pelvic evolution vary so much? And if childbirth wasn’t the big factor affecting pelvic evolution, what was? If birth constraints do not explain the pelvic variation of the past, that must mean we don’t really understand why human pelvises look the way they do today.In the absence of any simple answer to these questions, paleoanthropologists have started to consider more complicated possibilities.

One possible explanation has to do with changes in pelvic shape over the course of an individual’s lifetime. In their recently published study of human pelvic differences across age groups, Alik Huseynov of the University of Zurich and his colleagues hypothesize that variation in the pelvis may reflect age differences. In studying a small sample of individuals, they found that pelvis shape differs at different ages, even among adults, and to a greater extent in women than in men. Determining the age at death of an individual who was fully grown is challenging even for modern human skeletons; it’s nearly impossible in other hominin species. Yet, we know that some individuals lived long enough to wear down their molars whereas others didn’t, and that means there may have been hominins in the past who lived long enough to experience the pelvic changes that Huseynov’s study finds in humans. Paleoanthropologists haven’t been looking for this kind of developmental variation because we didn’t know it existed; up to now the hominin fossil record has been far too sparse and too fragmentary to demonstrate pelvic differences that might reflect the individual’s age at death. If Huseynov’s hypothesis is correct, then age at death is a variable that paleoanthropologists must begin to take into account when interpreting differences among individual fossils.

To find more than 1,500 fossils of the same species, representing nearly every part of the skeleton, was like winning the paleoanthropological lottery.

Another possible answer focuses on the role of nutrition in the formation of bone. In a review article published in 2012, Jonathan Wells of University College London and his coauthors hypothesized that problems with childbirth first arose with the advent of agriculture, which drastically changed the human diet. Wells and his colleagues argue that human pelvises aren’t under severe birth constraints, but that instead a carbohydrate-heavy diet, such as that eaten by people who had started growing their own grains, caused human pelvises to develop in a way that made birth more difficult. This result might be yet another example of how changes during a person’s lifetime may affect the morphology or shape of the pelvis. Although their paper serves mainlyto illustrate the need for further study in this direction, it presents an interesting idea that, if found to be correct, would have two important implications. First, as supported by some of the newest fossil discoveries, something besides childbirth drove hominin pelvic evolution; and second, to interpret pelvic variation in the past, paleoanthropologists need to know more about the diets of these hominins.

Clearly, testing these and similar hypotheses will call for developing a better understanding of what causes variation in the shape of the modern human pelvis; this much must be understood before we attempt to draw roads between the multitude of pelvic shapes found in the fossil record. It seems to me very likely that we scientists have spent so much time focused on figuring out how birth explains the evolution of the hominin pelvis (only to realize, belatedly, that it might not), that the real explanation may be something we haven’t thought of yet. It’s time for us to start looking for what we might be missing. Luckily, the lure of this mystery makes up for any fragment-caused frustrations our job may entail.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.